Read Like an Egyptian — Art in Ancient Egypt, Part 1

Probably only one percent of the ancient Egyptians were literate, and those literate few were royalty, nobility, upper-crust managers and administrators, at least some of the top military people, full-time priests and scribes. But many people could “read” what they were seeing, and understand it without knowing how to read hieroglyphs. The ideas and symbolic iconography were grounded in their culture; the art spoke to them even if their knowledge of the written text was, for the vast majority of the public, rudimentary at best — no doubt limited to a few basic glyphs. [more…]

Edition - March, 2014

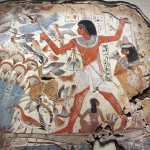

The paintings from the lost tomb-chapel of Nebamun

The paintings from the tomb of Nebamun are justifiably famous for their beauty and incredible dynamism. The British Museum purchased the panels that it has in 1821 . They were located by a Greek tomb robber named Giovanni d’Athanasi, who worked as an agent for Henry Salt in Luxor. Unfortunately d’Athanasi was angered by the finder’s fee offered and he refused to give up the location of the tomb from where the panels had been removed. The location of the chapel remains unknown to this day. [more…]

Edition - February, 2014

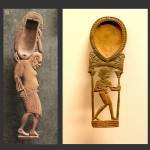

Ancient Egyptian Cosmetic Spoons of the New Kingdom

I was in the Louvre in Paris recently and was impressed by the exhibit of cosmetic spoons, so beautifully carved and so sinuously expressive. Although they are usually referred to as cosmetic, ointment or unguent spoons, their function has never been definitively established and they come in a variety of forms. This short article is a brief introduction to a much wider topic. [more…]

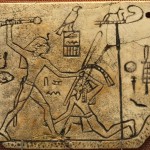

The Origin and Early Development of the Smiting Scene

The depiction of the king with mace raised above a helpless prisoner is one of the most prominent and enduring images of ancient Egypt. Although it has often been claimed that the origin for this iconic image lies in the Predynastic Era, this is unlikely. Not until the Narmer Palette do we see a possible model for dynastic developments of the image. These developments are traced here within the Early Dynastic Period [more…]

The Significance of the Crossed Arms Pose – Part 2: Osiris, The Osiris and the Osirides

Is it a futile activity to ask, as I do in this series of articles, “What is The Significance of the Crossed-Arm Pose?” It might be argued, for instance, that variations in the pose at death exhibited by royal mummies simply reflect what embalmers decided to do on the day, or at least the customary practice of a particular undertaker. Similarly, it might be argued that each individual anthropoid coffin might be expected to reveal some unique design characteristic, and that no significance should be attached to the specific hand/arm pose depicted on the lid. [more…]

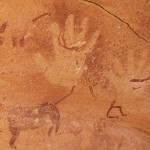

Book Review: Wadi Sura – The Cave of Beasts

The name “Cave of Beasts” comes from the strange headless creatures, an example of which can be seen on the cover of the book to the left. It comprises an estimated 8000 images over an area of some 120 square metres on the northeastern edges of the vast Gilf Kebir plateau. The book is edited by the much-published and respected archaeologist Rudolph Kuper, one of the major contributors to the archaeology of the area. [more…]

Edition - June, 2011

The Geese of Meidum

This iconic painting from the Old Kingdom Mastaba of Nefermaat and Itet is in The Egyptian Museum in Cairo and consists of three pairs of birds on one register. The right-hand central pair are universally accepted as Red-breasted Goose, Branta ruficollis, and the left-hand central pair as Greater White-fronted Goose, Anser albifrons. [more…]

By

By