By Andrea Byrnes. Published on Egyptological, December 7th 2011, Journal Edition 2

Abstract

Anthony John Arkell (1898 – 1979) was a pioneer of Sudanese archaeology, a precise and conscientious surveyor and excavator whose publications are still invaluable today. His work provided the framework within which conversations about the prehistory of the Sudan are discussed. When he returned to live and work in England Arkell was responsible for restoring the collections of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, its contents having been packed into 800 boxes during the Second World War. He went on to research and write about the Egyptian Predynastic, helping to revive interest in the pre-Pharaonic period. Anthony Arkell’s contribution to the archaeology of the Eastern Sahara is explored with reference to both his own publications and to comments made by other researchers about the range and value of his work.

Introduction

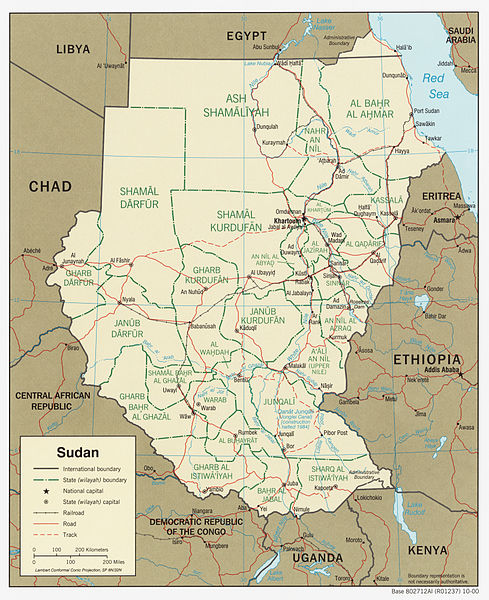

Figure 1. Map of Sudan. Courtesy: Norman B Leventhal Map Centre at the Boston Public Library, Creative Commons

Anthony John Arkell (1898 – 1979) was a pioneer of Sudanese archaeology, a precise and conscientious surveyor and excavator whose publications are still invaluable today. He moved to the Sudan in 1920 and lived there for nearly thirty years, not returning to England on a residential basis until 1948. He identified and named the Khartoum Mesolithic and Khartoum Neolithic, and investigated the prehistoric areas of the Sudan and their relationships with other areas. He created the framework within which all subsequent discussions of northern Sudanese prehistory have taken place. He published his research in a timely manner and was one of the earliest Saharan-based archaeologists to use radiocarbon dating. When he returned to live and work in England he was responsible for restoring the collections of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, its contents having been packed into 800 boxes during the Second World War. He went on to research and write about the Egyptian Predynastic, helping to revive interest in the pre-Pharaonic period.

Whilst other pioneers of Nile archaeology, ethnography and exploration, like W.M.F. Petrie, G. Caton-Thompson, E. Evans-Pritchard, Ralph Bagnold, Laszlo Almasy and others have biographies dedicated to them and are widely recognized for their work, Arkell is, today, comparatively less visible both as an individual and an archaeologist. He was not included, for example, in the second revised edition of Who Was Who in Egyptology, only being entered into the third revised edition in 1995 (Dawson and Uphill 1995, p.19).

This article hopes to provide a brief insight into a man whose work still forms the main body of data available on the subject of the Sudanese prehistoric period and contributed to important discussions about the prehistory of the eastern Sahara and prehistoric Egypt.

Much of this article uses Arkell’s own writings to provide an insight into his ideas and approaches but this would be a much shorter piece without Dawson and Uphill’s Who Was Who in Egyptology (1995) and Professor Smith’s 1981 biographical article in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, two years after Arkell’s death in 1979. Professor Harry Smith succeeded Arkell as curator of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, and valued Arkell most sincerely, saying: “Sometimes there appears a man or woman of such versatility and understanding as to transcend normal bounds. Such was Anthony Arkell” (Smith 1981, p.143).

Brief Biography

Anthony John Arkell was born on 29th July 1898 at Hinxhill Rectory in Kent, England, the product of a Christian upbringing. He was educated at Bradfield College, to which he won a scholarship, and Queen’s College, Oxford (Dawson and Uphill 1995).

The First World War broke out before Arkell had completed his studies and he joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1916. He received a Military Cross in 1918 in recognition for shooting down a German bomber at night without the aid of any modern instrumentation (Smith 1981, p.143).

In 1920 he joined the Sudan Political Service, spending nearly 30 years in the Sudan, from 1920 to 1948. During the entire first half of the 20th Century the Sudan was in the hands of an Anglo-Egyptian administration. Arkell served from 1921 until 1924 as Assistant District Commissioner for the Darfur Province before becoming acting Resident at Dar Masalit between 1925 and 1926. His marriage in 1928 to Dorothy Davidson was followed by a period as District Commissioner for Kosti (White Nile Province) from 1926 to 1929 and then for Sennar (Blue Nile Province) from 1929 to 1932. Smith says that both natural and human aspects of the present and past of the Sudan captivated Arkell – (Smith 1981, p. 143).

Although Arkell was one of the first archaeologists in the Sudan, he was not the only person studying the country, which was the subject of great interest to field scientists from various disciplines, including the ethnographer Evans-Pritchard whose publications about the Nuer are still of considerable value (Evans-Pritchard 1940, 1956) and Egyptologist George Reisner. Before his formal archaeological investigations Arkell wrote a series of articles in Sudan Notes and Records, looking at a range of topics. The Sudan Notes and Records was first issued in 1918 and is described by Spaulding and Kapteijns as “an important early forum for the integration of Sudan into the Western conceptual schemata of the twentieth century” (1992, p.140).

Arkell was well acquainted with the Sudanese politician Sir Douglas Newbold (to whom Arkell partially dedicated his book Early Khartoum, and who took an interest in Arkell’s excavations).

Arkell was notably instrumental in ending the slave trade between the Sudan and Ethiopia, and establishing villages for the freed slaves, who named themselves “the Sons of Arkell”. He was awarded an M.B.E. in 1928 and the Order of the Nile (Fourth Class) in 1931 as acknowledgement of this remarkable achievement. He was promoted to the position of Deputy Governor for Darfur in 1932 and held the position until 1937 (Dawson and Uphill 1995; Smith 1981).

Arkell trained under Sir Mortimer Wheeler in Britain whilst on leave and studied under Elise Baumgartel at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology when it was under the curatorship of Stephen Glanville, whom he eventually succeeded (Friedman n.d.). He was awarded a B.Litt at the University of Oxford for his history of Darfur Province (Smith 1981, p.144). On the retirement of the Acting Conservator of Antiquities in 1938, G.W. Graham, Arkell was appointed commissioner for archaeology and anthropology, working for the Sudanese Government as Commissioner for Archaeology and Anthropology from 1938-1948. Smith says that this was “very much at his own wish, against the feelings of some of his superiors in the Sudan Political Service, who foresaw high honours ahead of him” (Smith 1981, p. 144). He organized the museums of archaeology and ethnography, in Khartoum, encouraging the Sudanese to become involved in their development.

His archaeological and historical work was interrupted by the Second World War, when he served as Chief Transport Officer in the Sudan between 1940 and 1944 (Dawson and Uphill 1995).

Following the war he resumed his archaeological research and became Editor of Sudan Notes and Records, 1945-1948. He was also president of the Philosophical Society of the Sudan in 1947. Working at the sites of Shaheinab and Khartoum railway station he employed Sudanese assistants as well as European specialists (Arkell 1949, 1953). Of his approach to historical topics Spaulding and Kapteijns 1992, p.141) state:

“He not only drafted a history of Dar Fur but also made a special vocation of erecting innovative structures of theory to lend meaning to the ever swelling volume of facts. Being keenly aware of the provisional and contingent character of his interpretive architecture, Arkell was often the first to refurbish or demolish his own intellectual edifices in the light of new or better ideas – a particularly endearing quality that always left room for improvement in an admittedly imperfect world.”

His first wife died in 1945. He returned to England in 1948, prior to the independence of Sudan in 1956, and in 1950 he married his second wife, Joan Burnell. From 1948 to 1953 he was a lecturer in Egyptology at University College London, whilst remaining Archaeological Adviser to the Sudanese Government. He wrote three books about the Sudan – Early Khartoum, published in 1949, Shaheineb, published in 1953 and his History of the Sudan from the Earliest Times to 1821, published in 1951 (for which he was awarded a D.Litt by the University of Oxford in 1955). Smith says that the History of the Sudan educated two generations of Sudanese about their history and “taught them to think of themselves of a nation with a long history and a cultural tradition of their own” (Smith 1981, p.146). Arkell also wrote a number of papers and reviews which were published in academic journals.

Also in 1948, Arkell became the curator of the Flinders Petrie Collection of Egyptian Antiquities and professor of Egyptology at University College, University of London, where he catalogued the collection. He was appointed Reader in Egyptian Archaeology in 1953 and held this post as well as that of Curator of the Flinders Petrie Collection of Egyptian Antiquities at University College, London until his retirement in 1963 (Dawson and Uphill 1995). He contributed a large number of academic papers over this period, much of it focused on Egypt’s Predynastic. For his last “great adventure” at the age of 59 (Smith 1981, p.145) he joined the 1957 British Ennedi Expedition to Tibesti and Wanyanga (Arkell 1964). In 1995 he published his Prehistory of the Nile Valley.

Arkell was a committee member of the Egypt Exploration Society for many years. He was an expert on eastern African beads and became a member of the Committee for the Study of Beads, from its inception in 1960 until his resignation in 1963. Other notable members were Gertrude Caton-Thompson and C. Thurston-Shaw.

Following his retirement Arkell took a short course at Cuddesdon College in 1960, became Assistant Curate at Great Missenden from 1960 to 1963. He entered the Anglican Church, becoming Vicar of Cuddington with Dinton (Buckinghamshire) from 1963 until 1971 (Dawson and Uphill 1995).

Arkell retired to Little Baddow in Essex and died at the age of eighty-one, on 26th February 1980.

He was no relation of geologist William Joscelyn Arkell, who worked on the Egyptian Nile between 1926 and 1930 looking for Pleistocene remains.

Archaeological Achievements in Sudan

Figure 2. Khartoum Mesolithic microliths at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo by Andrea Byrnes

Anthony Arkell’s two great publications about the prehistory of the eastern Sahara were Early Khartoum (Arkell 1949) and Shaheinab (Arkell 1953). They covered, between them, his two most important excavations and his identification of two main periods of early Nubian prehistory, although he also covered other periods represented at those sites including the Nubian A Group and the Meroitic. “Early Khartoum” was the name that Arkell gave to the site he excavated at Khartoum Hospital and it became the type site for his Khartoum Mesolithic, which was composed of communities with an economy that used wild resources (savannah, riverine and light woodland) and manufactured pottery. Shaheinab was a site further to the north, also in the Sudanese Nile valley, which added domesticated animals to the economic mix. He regretted, in the preface to his volume on Shaheinab, that the need to reduce costs had impacted the quality of the publication (1953), but hoped that the lower cost would make it available to a wider audience. Both were accompanied by excellent photographs and illustrations.

On a site by site basis he was acutely conscious that to understand the archaeology he needed to understand the environment in which the archaeological record was formed, and that to understand the economy, the animal and plant remains needed to be collected and analyzed. Marks and Mohammed-Ali praised his work in this area: “Arkell’s interest in palaeoenvironmental reconstruction and his extensive use of faulal data recovere from his sites remain a model for such work” (1991, p.10). This was in an era when many archaeologists focused on the collection of stone tools, selecting the completed pieces and ignoring much of the rest of the archaeological record (Kozlowski and Ginter 1989). He recorded ceramics, stone and bone tools, faunal and floral remains and was able to comment on the economy and the environmental setting of the sites on which he worked (Arkell 1949, 1953).

On a regional scale, he was one of the first to observe that pottery found in the Khartoum sites was found elsewhere in the Sudan.

Outside the Sudan, Arkell was interested in exploring connections between the Khartoum Mesolithic, the Khartoum Neolithic and other areas, including those further north along the Nile Valley. He saw parallels between the Khartoum Neolithic and the Faiyum Neolithic (to the southwest of Cairo in Egypt), and suggested that the dates for the two periods were probably similar (1953). He observed that the pottery had similarities to that from Nuzi in northern Iraq and suggested that there might be a link between the two, with the invention of pottery of this type having been made, perhaps, in Asia, then spreading “right across Africa through what is now the (northern) Sudan and the southern Sahara, before it entered the lower Nile” (1949, p.115). In fact, it seems that the Khartoum Mesolithic and Neolithic pottery was the eastward reach of a western Saharan phenomenon, but Arkell had no access to that information, much of which has only been acquired since then, and his speculation was reasonable. His studies of pottery and bone harpoons also led him to suggest a connection between the Khartoum sites and areas to the west and south – including Taferjit and Tamaya Mellet (Arkell 1949, p.117-118). He was interested in the source of amazonite that was found at some of the sites, and speculated that it came from the Tibesti Mountains to the west in Libya. In the 1957 to Libya he was able to confirm the presence of amazonite in Eghei Zumma, a possible source for the Khartoum samples (Arkell 1964). At the same time he was also able to inspect pottery that had close parallels to that in the Sudan.

Arkell did not work in isolation and was in contact with other archaeologists, including Gertrude Caton-Thompson and Elise Baumgartel, both of whom were working on prehistoric Egyptian research at the time. Before taking on the task himself, he originally hoped that Caton-Thompson would undertake the Early Khartoum excavations herself, and referred to himself as “her less experienced understudy” (1949, p.viii-ix). He had studied briefly under Baumgartel in the 1930s (Friedman n.d.), and later discussed his excavations with her, thanking her in Early Khartoum for her suggestion that he expand the geographical scope of his work in future excavations (1949).

Archaeology had already become multi-disciplinary and Arkell was very aware of the benefits of bringing in specialists, commissioning reports from Dr D.E. Derry and Miss D.M.A. Bate on the human and vertebrate faunal remains. He demonstrated his appreciation of their contributions in his books, saying of the report by Miss Bates in Early Khartoum (1949), for example:

“[It) is thanks largely to her that it is now not the mere record of an excavation which had to be undertaken by the Sudan Government Antiquities Service but a work that will, I hope, encourage others, particularly in French North and West Africa, to elucidate still further the early connexions between the Nile valley and lands far to the west of it” (p.vii)

In Shaheinab (1953) he talked again of Miss Bate, expressing “mingled feelings of grief and gratitude” for the work she continued to contribute to the zoology part of the project during her illness, which preceded her death. He thought that it was “tragic that at present there is no zoologist to follow in her footsteps” (p.vii).

The photographs in all of Arkell’s books are a delight. He understood the importance of providing a visual record to compliment the text and was aware of both the limitations of the equipment and the conditions under which they were to be used. In Shaheinab he highlighted that printing papers and chemicals were vulnerable to heat and high humidity, and that there were often difficulties of unfavourable lighting conditions to be tackled (1953).

Fully aware of the potential of radiocarbon dating, only recently invented, he was able to acquire carbon 14 dates from charcoal and shell for the Khartoum Neolithic site of Shaheinab (Arkell 1953, p.vii). This was before the inherent flaws in radiocarbon dates had been recognized, after which they were (and still are) calibrated to give much greater accuracy. Arkell could not accept the discrepancy of 800 years between the date he obtained and his conviction that the Khartoum Neolithic was contemporary with the Faiyum Neolithic, also radiocarbon dated, in the north of Egypt (Arkell 1953. p.107; Arkell 1975; Caton-Thompson and Gardner 1934).

Arkell also used ethnographic data as a supplement to his archaeological observations, to help interpret the Khartoum findings and bring them to life. In Early Khartoum Arkell compared wattle and daub and matting techniques with those of the Tuareg, Dinka and Nuer of the Sudan. He quoted Evans-Pritchard to provide “an indication of the conditions under which the early settlement was probably inhabited” (Arkell 1949, p.108).

Arkell saw the future of Sudanese archaeology as the remit of young Sudanese in the Sudanese Government Antiquities Service. His vision for them says a lot about his feelings for archaeology:

“Before them lies an adventurous and honourable career in preserving the visible ancient monuments of their country and in bringing to light and reconstruction, from remains that will often be as fragmentary and unpromising as those of Early Khartoum, the history of their land, much of which is at present unknown” (Arkell 1949, p.vii).

In 1953 he expressed the hope that “some young Sudanese zoologist” would follow in the footsteps of Miss Bate (p.vii).

He was a considerable influence on others in the field of Sudanese archaeology. One of his employees in Khartoum, Peter Shinnie worked for him as assistant commissioner for archaeology, worked with him at Shaheinab and made advances in studies on Meroe, succeeding Arkell as Commissioner, and developing the Antiquities Museum in Khartoum. He was forced to leave the position during the “Sudanisation” of senior posts” in the early 1950s and later went on to become an important archaeologist, described in one obituary as “One of the leading pioneers of African archaeology (Clark 2007). Like Arkell, Shinnie never left the Sudan completely behind and in 1965 he began work at Meroe, where he worked for 11 seasons, becoming professor of archaeology at the University of Khartoum in 1966 until 1970 (Clark 2007), and founding the journal Kush. His book Meroe: A Civilization of the Sudan was published in 1967 and was reviewed by Arkell (1968).

Arkell also had an impact on the post-independence work carried out by Ibrahim Musa Mohammad in Sudan, notably in al-Fashir, Merbo, and Kutum between 1978 and 1981. His work combined archaeological surveys and small-scale excavations with ethnographic research (McGregor 2001).

Rock art was another interest of Arkell’s, one he shared with Hungarian Laszlo Almasy. Almasy is well known both for discovering a remarkable painted cave at the Libyan-Sudanese-Egyptian borders, now known as the Cave of Swimmers, and for his wartime work in the deserts of Libya and Egypt opposition to the Allies in the Egyptian desert. Arkell describes Almasy as a “friend” as well as a colleague, saying that he had an “uncanny” skill and “a wonderful flair for finding rock pictures” (1937, p.281). Arkell described the rock art that he inspected evocatively, demonstrating his knowledge of Eastern Saharan livestock at the same time (1937):

“The cattle with the horns that grow forward and downward unfailingly recall the Garamantian cattle, first described y Herodotus, to which Nachitgal related the rock drawings of cattle, all with their horns bent forward, which he found at Udeno in Tibesti. Cattle of a type in which the horns grow forward and downward are not uncommon in Darfur and Kordofan to-day, although this peculiarity does not prevent them from grazing in the normal manner: and it is not improbable that they are survivors of the old Garamantian stock, examples of which were owned by the people who made the rock paintings at Merbo” (p.283)

His work was not without problems, a point picked up by Marks and Mohammed-Ali when commenting on Early Khartoum and Shaheinab (1991, p.10), for example in this remark (together with others over the following pages, looking at other sometimes questionable reasoning and conclusions):

“In spite of all the justifiable praise which Arkell’s work deserves, hidden within thse two impressive reports were elements which led to considerable confusion and disagreement. Some of these problems have been solved, some merely have become passe, whilst others are still affecting some workers today.”

Occasional flaws in Arkell’s work do not undermine the fact that his work has formed the basis for all discussions about Khartoum archaeology and, like all early work, was bound to be modified by the activities of future researchers. Few archaeologists following Arkell have published both their findings and their interpretations so promptly, in such detail and so generously.

Arkell was clearly very aware of the secondary position of Sudanese archaeology when compared to that of Egypt, and was concerned to do justice to the subject. Whereas in Early Khartoum he dedicated the book jointly to his wife Dorothy and Douglas Newbold, in Shaheinab his dedication quoted Sir Arthur Keith, from New Discoveries relating to the Antiquity of Man:

“We are searching for the steps which led humankind from cave-life to village-life. All that Egypt has done for us is to convince us that these critical steps were taken by man long ago – well before the sixth millennium BC, but where they were taken and who took them we have still to discover.”

Arkell at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London

On his return to England in 1948, Arkell’s work in the Sudan was reflected in his new position as Honorary Curator of the Petrie Collection in London (Dawson and Uphill 1995) and a lecturer in Egyptology at University College London. The Petrie Museum was set up as a teaching resource for the Department of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at University College London (UCL), both established in 1892 through the bequest of the writer Amelia Edwards (1831-1892). Petrie had been the first person to be awarded the position of Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology and sold his personal collection to the museum in 1913 before retiring in 1933.

The collection had been packed into 805 crates, representing around five decades of Petrie’s excavations and purchases (Sivakumar 2009) and moved out of London in order to protect the collection from wartime bombing. It was Arkell’s task to unpack, catalogue, store and secure funding for the conservation of artefacts. Professor Smith says that it was a daunting task:

“Arkell manhandled the objects himself, with the help of only one assistant, taking the greatest care to preserve the association of the objects, which was often the only surviving clue to their identity. By patience, persistence, and hard physical work, he completed the task of unpacking and obtaining preliminary treatment of the objects, many of which had suffered. At a time of much pressure on college finances, by dint of ardent persuasion, he obtained funds for suitable cases and modern storage cupboards for the collection, and supervised their design. Once more, as at Khartoum, he shouldered the burden of identifying, sorting, cataloguing and exhibiting this unique collection” (Smith 1981, p.146).

Over a period of 14 years Arkell continued his work at the museum (now the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in Malet Place, London), recording the entire collection. The Petrie accessions register was only begun under Stephen Glanville, who was the curator between 1935 and 1945) and Arkell was left with the task of reconstructing both the provenance and the purchase history for thousands of objects, creating a database in the form of a card index (Sivakumar 2009), which has been an essential resource ever since. Smith concludes: “If Petrie was the father of the Museum, Arkell was its god-father” (1981 p.146). The museum, open to the public, now consists of around 80,000 objects and is no longer growing. Although it is far too big for its current premises, which are somewhat dimly lit, with old fashioned display cabinets, it is still an outstanding collection visited by researchers from all over the world.

During his tenure at the Petrie Museum, Arkell became an expert on the Predynastic of Egypt, following in Petrie’s footsteps and with Petrie’s vast Predynastic collection and writings available as a resource. He co-wrote a paper on the subject with Peter Ucko (who later became director of the Institute of Archaeology at UCL), in Current Anthropology in 1965, and later wrote the excellent The Prehistory of the Nile Valley (Arkell 1975), which included new material from recent excavations.

Throughout this period he also served as Archaeological Adviser to the Sudanese Government and it was in the decade folllowing his return to England that Arkell published Early Khartoum (1949) and Shaheinab (1953). Arkell retained a very real interest in the archaeology of the Sudan, reading and reviewing all new material published on the subject. He had a long written dialogue with O.G.S. Crawford, who had excavated at sites in the Sudan with Henry Wellcome before the First World War, and their correspondence between 1940 and 1956 on the subject of Sudanese archaeology, and other matters, is preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Crawford wrote an animated article about the Sudan called People without a History, published in 1948.

Arkell wrote a number of reviews in response to publications that followed his and was particularly articulate where they commented directly upon his work. He was quick both to pick up on dubious extrapolation and to point out examples where he had been misquoted or felt that researchers had failed to correctly observe the details in his work. His review of Fred Wendorf’s The Prehistory of Nubia, for example, highlighted a number of issues with which Arkell was not happy:

“In the Khartoum Variant industry, this report sees sites somehow related to my sites of Early Khartoum and Shaheinab (p. 789) despite the absence of important distinctive features. On page 1054 this becomes, ‘The pottery is nearly identical with that of Shaheinab,’ a statement with which, judging only from illustrations, I cannot agree, though I do agree that this pottery does appear to belong to the same family as Early Khartoum-Shaheinab, its simple rims suggesting to me a stage belonging to the very long period that must have elapsed between Early Khartoum and Shaheinab. Indeed none of the members of the Combined Expedition can have studied my Early Khartoum and Shaheinab thoroughly, or they would not have written on page 789 (as if the two sites were contemporary) that ‘no sites of “Mesolithic” age have been investigated’ (although ‘Mesolithic’ is just what the excavation of Shaheinab showed Early Khartoum to be), so that no one knows if the Khartoum Neolithic developed there or moved in from elsewhere.” (Arkell 1969, p.487)

Similarly, he commented of Forde-Johnston’s 1959 Neolithic Cultures of North Africa:

“There is some confusion in this chapter between the Khartum Mesolithic and the Khartum Neolithic. Despite what is stated, flaked celts (‘axes’) only occur in the latter, and the statement that the Badarian antedates the Khartum Mesolithic and the Fayyum Neolithic cannot be accepted” (Arkell 1960, p.116).

He was also, however, a generous reviewer when he admired the achievements of a writer, and his reviews were generally very well balanced between criticism and congratulation. Of Forde-Johnston’s book he concluded:

“In attempting a survey of all the evidence about the Neolithic of North Africa known to him, Mr. Forde-Johnston has produced a book that will be welcomed by all English-speaking prehistorians of Africa. It is only by the method he has pursued and by the collection of more evidence in the field that the truth will finally out.”

Later, in his Prehistory of the Nile Valley (Arkell 1975) he referred to Wendorf’s Prehistory of Nubia as an important work, and he cited it frequently.

Conclusion

In Professor Smith’s view Anthony Arkell was a Renaissance man (Smith 1981, p.143) with an appreciation of the rich Sudanese landscapes, people and past. Spaulding and Kapteijns (1992, p.140) described him, with appreciation, as a polymath. He was a conscientious man with a solid attention to detail. His ability to both excavate and interpret his discoveries was at the top of his field. He retained a close interest in Sudanese archaeology after his return to England, and often commented on the findings of others in academic publications. He also built on his role at the Petrie Museum to become an authority on Predynastic Egypt. He was clearly irritated by academic inaccuracies but sincerely appreciated good work, and although he was always willing to criticize where he saw flaws, he was also quick to highlight the good qualities and achievements of those who worked with him and whose research he appreciated.

Not as well known as some broadly contemporary foreign archaeologists working in Egypt, he was every bit as competent and his work was just as ground breaking. His legacy was an important one. He was hopeful that Sudanese archaeologists and specialists would take up where he was leaving off, and might have been disappointed that research in Nubia and beyond is still dominated by Western archaeologists.

From even this short distance in time he is a very difficult man to know, but from everything he wrote and was written about him he comes over as an infinitely likable man whom it would have been easy to respect and appreciate. Professor Harry Smith should certainly have the last word on Arkell:

“It was by his forthright character and his warm personality that Arkell won the respect, loyalty, and love of his colleagues and subordinates alike, both in the Sudan and at home. A deeply sincere but undogmatic Christian, he led by example, not by precept. He gave so much of himself to everything in which he engaged that others could not but respond; all that he did was in the spirit of services, not of self-seeking. He had a humorous twinkle in his eye, a faintly mordant wit, and a kindly, though unsentimental sympathy for the human predicament which endeared him to people” (Smith 1981, p.147).

There are archives with documents by and relating to Arkell, which should be a rich source of information for a future investigator (see below). It would be good to see a full biography of Anthony Arkell that would do credit to his work and his life.

Bibliography

Addison, F. 1949

Reviews: Early Khartoum. An Account of the excavation of an early occupation site carried out byt the Sudan Government Antiquities Service in 1944-5. By A.J. Arkell. Oxford University Press, London 1949

Antiquity, vol.24, No.95, p.151-154

Arkell, A. J. 1936.

Cambay and the Bead Trade

Antiquity, 10: 292-305

Arkell, A.J. 1937

Rock Pictures in Northern Darfur

Sudan Notes and Records 20(2), 1937, p.281-287

Arkell, A.J. 1940

Report for the Year 1939 of the Antiquities Service and Museums in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. Khartoum

Arkell, A.J. 1944

Report for the Years 1940-1943 of the Antiquities Service and Museums in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. Khartoum

Arkell, A.J. 1947

Discoveries which suggest the Existence of a Hidden Rock Temple: Colossal Statues Identified in the Sudan. A Sudanese Abu Simbel: Colossal Statues created by a Kushite King to emulate the Memorial of Ramses II

Illustrated London News Feb. 15, 1947, 214-215

Arkell, A.J. 1949

Early Khartoum. An Account of the excavation of an early occupation site carried out by the Sudan Government Antiquities Service in 1944-5

Oxford University Press

Arkell, A.J. 1953

Shaheinab

Oxford University Press

Arkell, A.J. 1953

The Sudan Origin of Predynastic ‘Black Incised’ Pottery

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol.39 (Dec 1953), p.76-79

Arkell, A.J. 1955

A History of the Sudan from the Earliest Times to 1821

Athlone Press

Arkell, A.J. 1963a

The Old Stone Age in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Sudan Antiquities Service Occasional Papers

A. J. Arkell 1963b

Was King Scorpion Menes?

Volume: 37 Number: 145 Page: 31–35

Arkell, A.J. 1964

Wanyanga and an archaeological reconnaissance of the South-West Libyan Desert: the British Ennadi Expedition, 1957

Oxford University Press

Arkell, A.J. 1968

Meroe Thus Far. A review of “Meroe, a civilization of the Sudan” by P. L. Shinnie.

The Journal of African History (1968), Volume 9, Issue 01, p. 159-160

Arkell, A.J. 1969

Review: The Prehistory of Nubia by Fred Wendorf

The Journal of African History, Vol.10, No.3 (1969), p.487-489

Arkell, A.J. 1972

Dotted Wavy Line Pottery in African Prehistory

Antiquity 1972, p.221-222

Arkell, A.J. 1975

The Prehistory of the Nile Valley, Vol.1

Brill

Arkell, A.J. and Ucko, P.J. 1975

A Review of Predynastic Development in the Nile Valley

Current Anthropology, 6, No.2 (1965), p.145-66

Caton-Thompson, G. and Gardner, E. 1934

The Desert Fayum

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland

Clark, P. 2007

Peter Shinnie

The Guardian, 30th October 2007

The Committee for the Study of Beads

The Royal Anthropological Institute

http://www.therai.org.uk/archives-and-manuscripts/archive-contents/committee-for-the-study-of-beads-a75 (last checked 1st December 2011)

Crawford, O.G.S. 1948

People without a History

Antiquity 22, p.8-12

Dawson, W.R and Uphill, E.P. 1995

Who Was Who in Egyptology

Egypt Exploration Society

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. 1940

The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People.

Clarendon Press.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. 1956

Nuer Religion

Clarendon Press

Friedman, R. n.d.

Elise Jenny Baumgartel 1892-1975

http://www.brown.edu/Research/Breaking_Ground/bios/Baumgartel_Elise%20Jenny.pdf (last checked 1st December 2011)

Forde-Johnston 1959

Neolithic Cultures of North Africa

Hays, T.R. 1974

‘Wavy Line’ Pottery: An Element of Nilotic Diffusion

The South African Archaeological Bulletin, Vol.29, No.113/114 (June 1974), p.27-32

Kozlowski, J.K. and Ginter, B. 1989

The Faiyum Neolithic in the light of new discoveries

In Kryzyaniak, L. and Kobusiewicz, M. (eds.)

Late Prehistory of the Nile Basin and the Sahara, pp157-79

Poznan

Marks, A.E. and Mohammed-Ali, A. 1991 (eds)

The Late Prehistory of the Eastern Sahel. The Mesolithic and Neolithic of Shaqadud, Sudan

Southern Methodist University Press

McGregor, A. J. 2001

Darfur (Sudan) in the Age of Stone Architecture c. AD 1000-1750: Problems in Historical Reconstruction. Memoirs No. 53.

Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology, Oxford.

Sivakumar, A. 2009

Transcription of A.J. Arkell card index to marks on objects in the Petrie Museum

http://ssndevelopment.org/acces_ssndevelopment/home/acces/public_html/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Arkell_Index.pdf (last checked 1st December 2011)

Smith, H.S. 1981

The Reverend Dr. Anthony J. Arkell

The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol.67 (1981), p.143-148

Spaulding, J. and Kapteijns, L. 1992

The Oriental Paradigm in the Historiography of the Late Precolonial Sudan

In O’Brien, J. and Roseberry, W.

Golden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the past in anthropology and history

University of California Press

Wendorf, F. 1968

The Prehistory of Nubia

Southern Methodist University Press

Archives

AIM25 1998-2008

GB 0102 PP MS 71

http://www.aim25.ac.uk/cgi-bin/vcdf/detail?coll_id=88&inst_id=19&nv1=browse&nv2=person (last checked 1st December 2011)

Durham University

The Sudan Archive

http://www.dur.ac.uk/library/asc/collection_information/cldload/?collno=177&fonds=Sudan%20Archive (last checked 1st December 2011)

Imperial War Museum

Private Papers of Lieutenant A. J. Arkell M.C. M.B.E. R.A.F.

Catalogue number: Documents.6706

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030006532 (last checked 1st December 2011)

The National Archives

GB/NNAF/P139693

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/nra/searches/subjectView.asp?ID=P758 (last checked 1st December 2011)

Pitt Rivers Museum

Arkell Papers

Two boxes of material, relating to Arkell’s research on beads and the bead trade, especially in North Africa

http://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/manuscripts/arkellpapers.html (last checked 1st December 2011)

Smithsonian Institute

The Arkell collection: Beads–Research. Collecting African beads. Call number NK7300.B365

http://collections.si.edu/search/results.jsp?q=record_ID:siris_sil_545438 (last checked 1st December 2011)

SOAS Archive

PP MS 71

http://squirrel.soas.ac.uk/dserve/dserve.exe?dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqDb=Catalog&dsqCmd=Show.tcl&dsqSearch=%28RefNo==%27PP%20MS%2071%27%29 (last checked 1st December 2011)

Photo Credits

Figure 1. Map of Sudan. Courtesy: Norman B Leventhal Map Centre at the Boston Public Library, Creative Commons.

Figure 2. Khartoum Mesolithic microliths at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo by Andrea Byrnes

Figure 3. Khartoum Mesolithic Incised Wavy Line pottery. Copyright Trustees of the British Museum

By

By