Published on Egyptological, In Brief, 27th February 2012.

By Andrea Byrnes

Introduction

Whilst reading up on the Third Intermediate Period for an article on the 22nd Dynasty, I was surprised to see how important oracles had become during the late New Kingdom and early Third Intermediate Period as a means of acquiring decisions by all levels of society.

This short piece introduces the oracle and its role in Egyptian society.

What was the oracle?

The word oracle derives from the Latin verb orare, to speak. Oracles were common to a number of cultures and are particularly associated with Classical Greece, where oracles were usually living individuals, male or female. In Egypt the oracle was a statue, usually hidden in the centre of the god’s temple, but taken out into the streets on procession during festivals for the public to consult. In either form the purpose of an oracle was to channel the messages of god, giving answers to specific questions. It was typically the job of the priesthood to interpret some of these answers.

In which periods were oracles used?

Oracles may have been used as far back as the Middle Kingdom, but were certainly used throughout the New Kingdom period, and are probably best attested from Amarna where the oracle was one of the principal methods by which villagers obtained justice. As far back as the Eighteenth Dynasty the powerful king Thuthmosis III justified his claims to the throne by reference to a pronouncement by the Oracle of Amun. At the end of the New Kingdom and in the early Third Intermediate Period the oracles at Thebes, particularly the Oracle of Amun, were used at all levels of society, even ratifying government policy in Thebes. By the time Alexander the Great visited Egypt the Oracle of Amun at Siwa was so famous that Alexander travelled across the desert to consult it.

Which deities were consulted via the oracles?

All regions of Egypt had deities that were particularly important to the residents of that area, for example Amun at Karnak, Ptah at Memphis, and the deified Amenhotep I at the workmen’s village of Deir el-Medineh. Whilst the elite and high officials were permitted to consult the senior deities of the region, “[m]ore humble persons did not trouble the state gods; they were expected to consult their own specific local deity who, presumably, would have a better knowledge of local affairs” (Tyldesley 2000, p.148).

How was the oracle consulted?

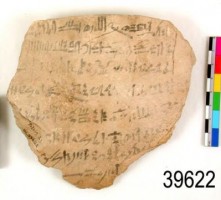

Questions could be posed to the oracle in either verbal or written form. In Deir el-Medineh scribes wrote down questions on stones, so many of the queries have been preserved and concern business, domestic, romantic, health and minor legal matters. The statue, held on the shoulders of priests, was tilted one way or another to indicate a yes or no response to the petitioner. John Romer describes a procession through Deir el-Medineh in evocative terms:

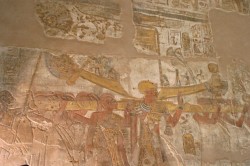

King Amenhotep appeared to the gaze of his worshippers as he was carried in a sort of sedan chair by six ritually-purified workmen accompanied by workmen-priests with large ostrich-feather fans who carefully and rhythmically enveloped the sacred image in clouds of incense (Romer 1984, p.102)

The oracles as legal arbiters

Oracles could be consulted over matters concerning legal disputes that were either too small to take to the more formal systems of judgement, or would cost too much to take to the local courts. Entire cases could be presented to the oracle which would make a judgement in favour of one party or another.

Towards the end of the New Kingdom the oracle could be presented with a list of suspects for a crime and the scribe would interpret the oracle’s decision on who was the guilty party. David (2002, p.289) believes that “[t]he practice was clearly open to competition and abused, and marked deterioration in the system” although Tyldesley argues that at Deir el Medineh blatant abuse of the system would have been obvious to the populace. Tyldesey believes that however the oracle worked in practice the verdicts made by the oracles “almost always concurred with local opinion” (2000 p.150).

For more information about the legal role of the Oracle see Joyce Tyldesley’s “Judgement of the Pharaohs” (2000).

The Oracles as divine decrees

In the Third Intermediate Kingdom the oracles could be consulted about the health of a new born child. A priest would interpret an oracle’s answer and this would be recorded on papyrus and given to the family. The papyrus was rolled and placed in a bag or cylindrical amulet, which was worn for good luck by its owner. The oracles would usually prophesise good health, wealth and long life, and ward off evil. An examples at the British Museum (EA 10321) records that a male child was given divine protection against illness.

What if the answer was not the one required?

On personal matters, although an oracle might answer a question in a given way, the private petitioner was not obliged to accept the answer. Oracles of other deities might give different answers, so if the oracle representing one deity gave an undesirable answer, there was always the option to consult a different oracle in the hope of obtaining a more acceptable response.

In legal matters the decision of the oracle was binding.

Conclusion

The oracle served a useful role in Egyptian society, giving the general public the opportunity to discuss important domestic, business and legal matters directly with the divine, via its earthly representative. Increasingly in use by the northern kings for implementing government policy in Thebes during the Third Intermediate Period, the oracles became part of a theocratic system of rule.

Bibliography

David, R. 2002

Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt

Penguin Books

Hornung, E. (Translated by Baines, J.) 1971/1982

Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt. The One and the Many

Cornell University Press

Pinch, G. 1994/2006

Magic in Ancient Egypt

The British Museum Press

Romer, J. 1984

Ancient Lives. The story of the Pharaohs’ Tombmakers

Phoenix Press

Shaw. I and Nicholson, N. 1995

The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt

The British Museum Press

Taylor, J. 2000

The Third Intermediate Period (10690664 BC)

In Shaw, I.

The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt

Oxford University Press

Tyldesley, J. 2000

Judgement of the Pharaohs. Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt

Phoenix Paperback

(Review of this title available in Edition 4 of Egyptological)

Wilkinson, T.W. 2010

The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. The History of a Civilisation from 3000BC to Cleopatra

Bloomsbury

By

By