By Barbara O’Neill. Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 2. September 9th 2011

Introduction

Animals were a ritually charged symbol of life, lavishly represented in Egypt’s literature, arts, and crafts. They were believed to be creatures of the gods with the ability to communicate directly with a range of deities. Indeed, animal vocalisation was perceived as a secret language understood by the gods. The prominence of animals within Egyptian elite culture however, did not result in the animal loving traditions which exist today. Animal necropolises throughout Egypt bear witness to the fact that many creatures, including those we now value as domestic pets, were routinely strangled mummified and presented as votive offerings to gods with which the animals were associated.

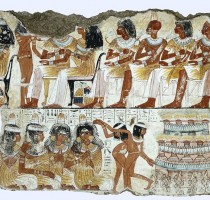

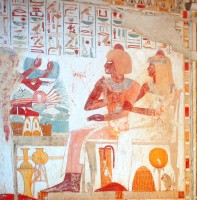

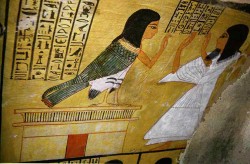

In this article, I will investigate some of the key elements which make up the ‘offering table scenes’ within Egyptian tombs. What is the significance of the presence of small dogs, lively monkeys or elegant cats under the chairs of tomb owners in these scenes? Are these simply pets accompanying deceased owners to the afterlife, or is there more to the presence of animals within the decorative programme of Egyptian tombs? [Figure 1]. After exploring the presence of ‘pets’ beneath the chairs in these scenes, I will focus on the significance of animals within the narrative imagery elsewhere in the tomb.

The Offering Scene

The earliest known offerings made to the deceased in Predynastic Egypt took the form of a loaf of bread placed on a simple reed mat. In Early Dynastic tombs, offerings of beer, bread, and other items deemed necessary for the afterlife were deposited in wall niches within the burial chamber itself. As private tombs became more complex, ‘slab stelae’ appeared in offering chapels adjacent to the burial chambers. The slab stele bore a single scene of the deceased, seated before a table of offerings.

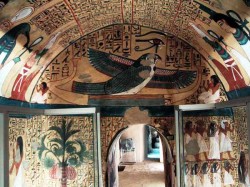

By the Fifth Dynasty, more expansive narrative imagery developed in the offering chapels of elite tombs. The focus of the chapel was the ‘false door’ which magically allowed the kA (the spirit of the deceased) access to his chapel and to the offerings represented there. The ‘offering table’ element developed into a composition carved or painted upon the false door. This symbolic door acted as a threshold between the realms of the living and the dead. The imagery of offering scenes continued to evolve into a more extensively detailed element of the tomb’s decorative programme usually located on western-facing walls. The ‘west’ was understood as the land of the dead, with the deceased often referred to as ‘westerners’. Increasingly elaborate imagery within the tomb ensured a ‘magical’ supply of everything necessary for the afterlife.

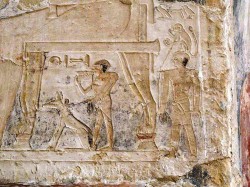

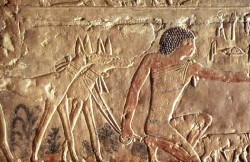

Egyptians liked to maintain cultural continuity, often mixing old traditions with new developments. The initial simplicity of early offerings is reflected in the hieroglyph for ‘offering’, Gardiner sign R4 Htp, which represents a loaf of bread on a reed mat. In ancient Egyptian life, no meal was complete without bread and beer; both were a significant part of the daily diet for every Egyptian. Several hundred ancient loaves still exist within museum collections all over the world. Virtually all were recovered from elite tombs. These loaves sometimes match images of the conical Gardiner sign X2, t, or half-spherical sign X1 t loaves depicted on offering tables. Elongated slices of bread from conical loaves are often represented as tall reeds on Old Kingdom offering tables [Figure 2]. The two elements of the reed, indicating ‘abundance’ and the loaf referencing ‘sustenance’, appear on early offering tables as combined elements, symbolising eternal nourishment for the tomb owner.

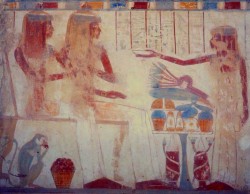

Figure 3. Banquet Scene, Tomb of Nebamun. Eighteenth Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of the British Museum

Offering scenes continued to become more complex, expanding to include long lines of offering bearers from the estates of the deceased bringing food in processed (cuts of meat and baskets of vegetables) and unprocessed forms (animals and birds) for the benefit of the tomb owner. Scenes showing the production of burial goods and food preparation also appeared. By the New Kingdom, the offering scene narrative had grown to include entire banqueting scenes, complete with guests and musical entertainment [Figure 3]. From a simple loaf on a reed mat, a veritable production line culminating in an elaborate funerary feast had developed.

Furnishing the Offering Scene

Figure 4. Folding Stool, Tomb of Userhat Thebes. Eighteenth Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of Osirisnet

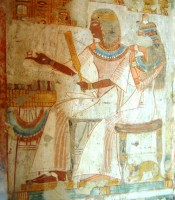

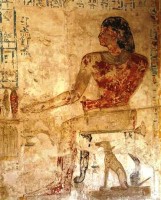

The thematic arrangement of the deceased, usually seated at an offering table laden with food (often standing during the First Intermediate and early Middle Kingdom phases), continued until late in the Dynastic era. Variations on the number and shape of the loaves, the height of the table, the style of the chair, and the shape and number of jars and containers can sometimes help to date an offering scene chronologically. However, one must tread carefully in dating any Egyptian imagery using art-historical criteria due to the popularity of an archaizing tradition. This meant that stylistic references from the past were utilised in tomb imagery of a significantly later era. Ointment pots, unguent vessels, and floral friezes represented amongst the burial equipment in the tomb of Montuemhet, mayor of Thebes in the Twenty Fifth Dynasty (c. 525 BC) are almost identical to those in the tomb of Rekhmire (c. 1475 BC), a New Kingdom vizier to Thutmosis III. Montuemhet based elements of his tomb’s artistic programme on that of Rekhmire’s, “virtually lifted out of the New Kingdom and reproduced some eight centuries later”, (Der Manuelian, 1985).

In the New Kingdom tale Truth and Falsehood (Papyrus Chester Beatty II) we learn that a conventional way of honouring someone in ancient Egypt was to seat one’s guest comfortably and offer refreshments; “The youth brought his father inside; made him sit on an armchair, placed a footrest under his feet and put food before him” (Lichtheim, 1973). Most people in an ancient Egyptian household however, would sit on the floor; chairs denoted rank and status .

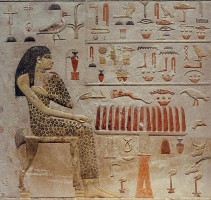

Chair design evolved from three or four-legged wooden stools (some of which folded flat) first recorded in the Early Dynastic period [Figure 4]. Stools continue to be used throughout the Pharaonic era with ornate examples found amongst the furniture in Tutankhamun’s tomb. Low backs, which began to transform stools into chairs, began to appear during the Old Kingdom, with full-backed chairs in place by the Middle Kingdom. Although full-backed chairs with armrests have been recovered from royal tombs of the Old Kingdom, the design of seating represented in offering scenes seems to follow a chronological pattern. Stools depicted in Old Kingdom scenes are typically finished with papyrus umbels, as in the stool of Nefertiabet, daughter of Snefru [Figure 5]. They gradually acquire low backs, transforming these sometimes ornate stools into chairs [Figure 5]. This low- backed style continued into the Middle Kingdom. By the New Kingdom, more chairs are depicted as high-backed, sometimes elevated on a dais appearing almost ‘throne-like’. Even with accompanying cushions and footstools the chairs represented in offering scenes seem more about appearance than comfort! [Figure 6].

There is no evidence that tables were used for everyday dining in ancient Egypt. Most people would sit on the floor to eat, as they sometimes do in parts of Egypt and the Middle East today. Elegant table-stands which held a cup or a single dish are sometimes shown alongside guests in banqueting scenes. A wooden table of this type was found in the Nineteenth Dynasty tomb of Kha and Merit near Deir el Medina. Gaming tables also appear within related imagery; their table-tops fashioned into grids for board games such as Senet. Images of the deceased playing board games had a ritual purpose. Senet was associated with communication between the living and the dead, with success in the game related to the movement of the bA (an aspect of the soul) between the spheres of life and death. Although Senet may have been a game for more than one player, the deceased is almost invariably presented playing alone; perhaps referencing the final, unaccompanied passage to the afterlife [Figure 7].

Under the chair

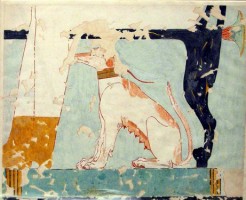

The scholar Dorothea Arnold has noted that animal representation began in tombs and temples around the Fourth Dynasty, reaching “an unsurpassed peak” in the Fifth Dynasty (1998). The presence of small mammals under the chair of the deceased is attested from offering scenes of the Fourth Dynasty. Dogs and monkeys are the first animals to appear in this favoured position. Somewhat surprisingly perhaps, with the perceived close association between cats and the goddess Bastet (a deity often represented in the form of a cat) felines appear significantly later in this repertoire. Other items found under chairs are related to occupation or functioned as signals of status during the life of the deceased. Objects represented here include mirrors, scribal palettes, arrow quivers, and chest-like coffers [Figure 8]. Labels accompanying painted representations of chests, boxes and coffers under the chair indicate that they often ‘contained’ the ubiquitous funerary offerings of incense (snTr), cloth (mnxt) and perfumed ointments (mDt). Representing these items pictorially, or through inscription was enough to ensure a magical and unending supply.

Dogs in Tomb Art

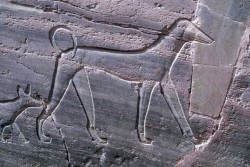

Dogs as guards or companions have a long and illustrious history in Egypt. A dog described as a saluki, was buried under the entranceway of the First Dynasty tomb of Queen Her-neith at Saqqara. The dog may have been associated with Anubis or inpw, an important god of the dead. Modern concerns over specific species identification and whether Anubis is represented by a domesticated dog, a wild dog or a jackal are most likely irrelevant. Ancient Egyptians are described as displaying “ambivalence in the symbolism applied to dogs, jackals, and the deities manifested in some of them” (Baines, 1993), [Figure 9].

With almost every detail of tomb imagery bearing multiple levels of meaning, it is refreshing to learn that dogs depicted under the chair of the deceased may simply have been the family pet [Figure 10]. Dog names are sometimes included on associated labels in these scenes. Names found here, and on leather and metal dog collars recovered from tombs, include ‘The Good Guardian’, ‘One Fashioned as an Arrow’, ‘Brave One’, ‘North Wind’ and, perhaps more mundanely, ‘Blackie’ and ‘Useless’! An inscription from a tomb at Giza relates the remarkable honour shown to a dog favoured by a king of the Fifth or Sixth Dynasty. Unfortunately, the small mastaba tomb originally constructed by royal craftsmen for this dog was built over in antiquity; its original blocks reused. Full details of the dog, its owner, and the king who honoured both are now lost to us. Happily, the complete inscription from a stele originally situated within the burial chamber was found intact and included a partial image of the owner holding the dog on a leash. The inscription reads

“The dog which was the guard of His Majesty, Abuwtiyuw is his name. His Majesty ordered that he be buried ceremonially, that he be given a coffin from the royal treasury, fine linen in great quantity and incense. His Majesty also gave perfumed ointment and ordered that a tomb be built for him by the gangs of masons. His Majesty did this for him in order that he might be honoured before the great god, Anubis”. (Reisner, 1936).

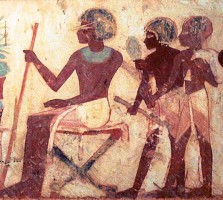

The scholar Regine Schultz notes that dogs appearing in Old Kingdom tomb reliefs appear in very different contexts from other animals: “They are not just pets; they are attributes of their masters, and express in the different contexts dynamic and magical power, (especially in combination with monkeys and dwarves), vigilance, and protection” (2006). In a beautifully carved scene from the tomb of the nobleman Ty at Saqqara, the deceased is shown being carried on a palanquin, alongside which walk his servants, one of whom leads a small dog and a monkey.

This type of scene served as a metaphor for the funeral procession, which at this stage in the Old Kingdom was not included in tomb imagery [Figure 11]. Around two hundred years later, a very similar scene occurs in the Middle Kingdom tomb of the nomarch Djehutyhotep at Deir el Bersheh. Djehutyhotep’s pet dog Ankhu, a quirky, low-slung basset hound-type dog, appears twice in his owner’s tomb. One poignant image shows Ankhu walking alongside Djehutyhotep’s funereal palanquin in the company of offering bearers and mourners [Figure 12].

Figure 12. Ttomb of Djehutyhotep with pet dog Ankhu. 12th Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of the British Museum

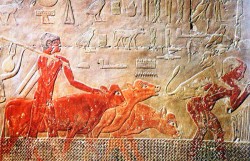

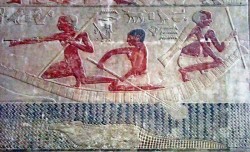

Figure 13. Dogs bringing down Gazelle and Oryx, Tomb of Ptahhotep, Saqqara. Fifth Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of Osirisnet

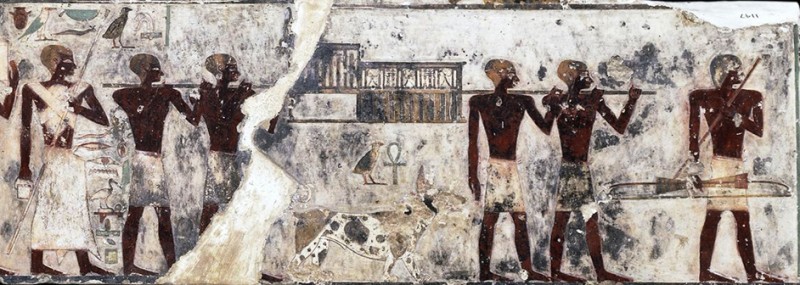

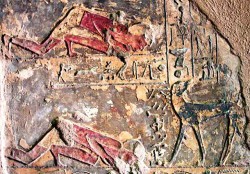

Dogs in pursuit of gazelles and other wild animals are a common theme in ‘Hunting in the Desert’ imagery which appear in elite tombs from the Fourth Dynasty [Figure 13]. The hunted gazelle was one of the earliest and most prevailing images dating from Predynastic Egypt, with the hunter (canine or human) and the hunted “forming binary pairs, connoting control versus chaos” (Strandberg, 2009). These scenes, along with similar scenes depicting hunting and fishing in the marshes, are often referred to as ‘scenes from everyday life’. The desert landscape was understood as the place where death was transformed into new life; related imagery of a gazelle giving birth or nursing in a desert setting is believed to have symbolised the transition from life to rebirth in the afterlife.

There are a number of words for ‘dog’ in Egyptian, including iwiw. As with other animal names, this word may have had onomatopoeic origins. Other terms describe particular types of dog. The most common ‘breed’ was known as the Tsm, often compared to greyhounds or basenji-type dogs. Tsm are represented both as pets and as active participants in hunting scenes. This sharp featured, pointed-eared dog, with a tightly curled tail is the most common form of domesticated dog depicted from the Predynastic era onwards.

Figure 15. tsm and bHn type Dogs in tomb of Sarenput I, Aswan. Twelfth Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of Osirisnet

Another type of dog, with rounder features and floppy ears is also well attested; this ‘breed’ is usually referred to as bw, or bHn. There are many variations of this word, which in its verbal form can also mean to ‘drive off’ or to ‘eliminate foes’ [Figure 14]. Differentiation between wild and domesticated dogs is usually indicated through the collar worn by pets and hunting dogs, or by the leash held by a handler or the tomb owner [Figure 15].

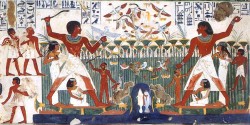

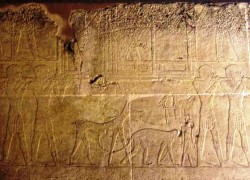

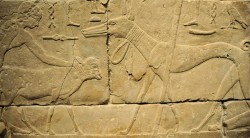

Figure 16. Cattle fording scene, with calf. Tomb of Ty, Saqqara. Fifth Dynasty. Photograph courtesty of Osirisnet

Domesticated canines also appear in agricultural scenes where they maintain a vigilant presence during planting and harvesting activities. Elsewhere, dogs sustain an alert and defensive pose as herds of cattle cross dangerous fords. Here the dog acts as a counterbalance to the ever present danger of crocodiles and hippopotami. In the formulaic pattern of these ‘cattle fording’ scenes, the foreman of the herders is often portrayed in a highly attentive pose. The crossing was fraught with danger from various riverine hazards, threatening to both cattle and herdsmen. Accompanying text indicates that the men uttered spells to render the ever-present crocodiles harmless or even blind to their presence. In a related scene, a herdsman is often shown carrying a young calf across the river, followed by its mother, as the cow frantically calls to her calf [Figure 16]. The chief herdsman often uses colourful expletives in hurrying on the herd and herdsmen that follow.

Such scenes allow us to share a moment in time as the overseer alerts everyone to the presence of a lurking crocodile; his pointed finger a ritually charged gesture to warn off danger [Figure 17]. There are layers of meaning within this scene which at its most literal, may have been true to life. On the symbolic level, the young calf was associated with the rising sun and in river-crossing scenes may represent Ihy, the son of Hathor. In the Coffin Texts, Ihy bears the ‘water of life’ in his hands as he emerges from the primeval waters of creation, facilitating the deceased’s journey to the afterlife.

Even though his iconography is sometimes that of a child or a young calf, Ihy’s role as protector was well understood; he is described as an intermediary between humankind and the gods. Hathor was a goddess crucial to the regeneration of the deceased and one of her son’s principal roles was to provide access to his mother. Therefore, on the symbolic level, scenes of cattle crossing the river may indicate the deceased’s safe navigation to the afterlife, assisted by the divine child, Ihy. Literally or figuratively, the dog is often shown ‘on guard’ within the fording scene narrative, ensuring magical protection for the deceased in the presence of Hathor and her son [Figure 18].

Monkey Business in Tomb Art

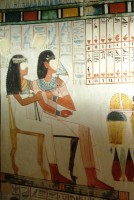

The earliest known depiction of a monkey in a tomb scene occurs in the Fourth Dynasty tomb of Nefermaat at Meidum [Figure 19]. Small monkeys are frequently represented under chairs in offering scenes from the early Old Kingdom. These animals are often represented in such detail that specific breeds of monkeys have been identified, including the green or long-tailed monkey, Barbary macaques, and patas monkeys. One term for ‘monkey’ was ky, possibly another example of the onomatopoeic element within animal names. Often depicted in playful poses, these animals are usually leashed and sometimes provided with bowls of fruit to sustain them in the afterlife. Monkeys are found most often under the chairs of women, referencing female regeneration [Figure 20]. By the Eighteenth Dynasty, depictions of small monkeys and larger apes are well attested from various locations in the tomb and within temple imagery at Thebes and elsewhere.

Figure 20. Monkey under chair of daughters of deceased. Tomb of Userhat. Eighteenth Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of Osirisnet

Baboons were less likely to have been tamed as pets, though they do feature in the narrative imagery of private and royal tombs. These highly intelligent primates had a complex iconography from the Early Dynastic era. Baboons were considered sacred to a range of deities including Thoth, Re, and Khonsu. Although loosely associated with the sunrise, they are also associated with lunar deities and with the moon. Baboons were believed to shriek at dawn and are described as dancing in the eastern horizon, filled with joy at the rising of the sun. They are often depicted with arms raised, greeting the sunrise. The baboon was believed to protect the deceased during the journey to the netherworld. Thoth, a lunar deity and the god of wisdom, was believed to have been taught the ‘holy words’, or ‘hieroglyphs’ by a baboon; all sacred baboons were considered literate! Sacred or not, remains of mummified monkeys and baboons recovered from animal necropolises show that there was little understanding of the animal’s needs or natural behaviour; most show signs of skeletal deformities related to close confinement or nutritional deficiencies.

The Cat in Offering Scenes and in Egyptian Life

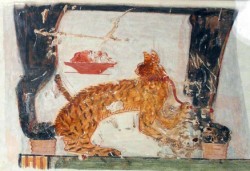

Figure 21. Cat Hunting in the Marshes. Tomb of Nebamun. Eighteenth Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of British Museum

As noted earlier, we tend to associate cats closely with ancient Egyptian culture, although in the chronological framework the cat makes a relatively late entry into tomb art as domesticated pets predated by both dogs and monkeys. Short tailed wild cats are represented in ‘hunting in the marsh scenes’ of Old Kingdom tombs, later revisited as a popular motif of the Eighteenth Dynasty [Figure 21]. The wild cat also functions mythologically in the narrative imagery of the New Kingdom, where the ‘solar cat’, armed with a knife, protects the rising sun from the serpent, Apophis. When domesticated cats finally arrived in the favoured spot beneath the chair within Middle Kingdom offering scenes, it was only to discover that dogs and monkeys were already curled up there from the Old Kingdom.

The earliest representation of a domesticated cat appears in a Middle Kingdom tomb scene at Beni Hassan. This is said to be the first image ever of a cat confronting a rat. Later, satiric representations continue the enduring tradition of cat versus rat on vignettes recorded on papyrus. A tomb, excavated by Petrie and dated to the same Middle Kingdom era as the Beni Hassan imagery, contained the bones of seventeen cats. The burial also contained a row of small bowls which were believed to have held food offerings to sustain the cats. It isn’t until the New Kingdom, however, that pet cats appear fairly frequently under the chairs of women and less frequently men, within the offering scenes of Theban tombs. Like the monkeys, cats are often tethered and are sometimes depicted in a range of feline poses, such as scratching, or gnawing on fish [Figure 22]. Most of these cats aren’t named, although there are notable exceptions. The cat in the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Puyemre at Thebes is named nDmt or ‘pleasant one’, while a cat thought to belong to Thutmosis, eldest son of Amenhotep III, was buried in her own elaborately carved sarcophagus. The Prince’s cat was named miw, possibly another onomatopoeic Egyptian word which translates simply as, ‘the cat’!

The cat’s association with the goddess Bastet is well attested. Bastet provided protection for the deceased and like, Hathor, she was associated with the sun god, Re. Bastet could be malignant and ferocious or peaceful and benign. This goddess was more often associated with lionesses until the Middle Kingdom, when her iconography evolved into a milder feline form. At around the same time, cats began to feature more frequently as pets within offering scene imagery. Although cats are sometimes depicted in a playful attitude under offering scene chairs, the more frequently found static pose is believed to have been modelled on the hieroglyph for Bastet , Garduber’s E13, referencing the protective role of this goddess for the deceased.

During the Late era according to Herodotus, it was an offence to kill a cat, even accidentally. This ancient writer described how Egyptians would flee the scene of a cat death for fear they could loose their own lives if implicated. Although very possibly an exaggerated account, such high regard remains somewhat ironic when we consider that cat necropolises throughout Egypt (particularly at Bubastis, Bastet’s primary cult-centre) are estimated to have contained millions of kittens and young cats, put to death and mummified as votive offerings. Although the cat’s position ‘under the chair’ may have come relatively late, it was clearly a well earned place for the more fortunate family cat!

Hunting and Fishing in the Marshes

Scenes of desert hunting and fishing in the marshes were usually placed in proximity to each other. Agricultural activities and scenes depicting animal husbandry also appear adjacent to each other, though away from scenes of desert animals and the marshes. There were good reasons to keep these depictions separate. Symbolically, the hunting and fishing scenes are associated with the control of chaos, whereas the agriculture, animal husbandry, and other manufacturing and production scenes functioned to ensure a well supplied afterlife. Although the scenes were related, no respectable tomb owner would wish these two ritually charged categories to become entangled!

Images of the tomb owner accompanied by his wife, children, and other members of his extended family are frequently portrayed enjoying a range of riverine leisure pursuits known collectively as ‘fishing and fowling in the marshes’. Fishing and spearing scenes are first attested from the Old Kingdom, when the possibility of an afterlife beyond the tomb for non-royal Egyptians began to develop. By the Ramesside era, the emphasis on scenes of ‘daily life’ was gradually overtaken by vignettes from the Book of the Dead, “most probably reflecting a change in funerary beliefs” (Kanawati, 2001). Narrative imagery began to focus on the afterlife of the deceased in the netherworld [Figure 23]. In this image Inerkhau addresses his bA, the element of his soul (represented as a bird) which allowed the deceased to move between the realms of the living and the dead.

Although the repertoire of artistic elements which appear in an elite tomb were chosen by the tomb owner, such scenes tend to be formulaic. One scene of hunting or fishing will never be identical to another, but the complexity of the message remained the same;

- the control of chaos;

- the assurance of rebirth in the afterlife; encoded within

- an idealised portrait of family life.

It is assumed that these scenes portray actual pursuits of the tomb owner, though there is no firm evidence that this was always so. Aspiration towards an afterlife where one was rich enough to enjoy such leisurely pursuits must remain a consideration. Not every experience pertaining to the reality of life was included within the tomb’s imagery. Scenes of the dangerous pursuit of hunting hippopotamus are popular although, curiously, there is not a single example of a violent confrontation between man and crocodile, but exclusively between crocodile and hippopotamus. Why this is so, is unclear. What can be understood is that tomb owners must have made a selection from the ‘daily life’ situations he either experienced or had aspirations towards, and equally omitted those, that for a variety of reasons he didn’t wish to experience or relive in eternity.

Fish and Fertility

Figure 24. Nakht and wife fishing and fowling in the Marshes. Eighteenth Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of Osirisnet

In the ‘marsh’ scenes there are again layers of meaning within what might, at first glance, appear simply as the tomb owner accompanied by his wife, spear fishing in the marshes (Figure 24). This was another ubiquitous image belonging to the genre of ‘scenes from everyday life’. Do such scenes represent the couple’s fertility, based on a pun between the Egyptian verb sti ‘to shoot’ and sTi ‘to ejaculate’? This remains unclear, although the Book of Kemit, an Eleventh Dynasty ‘text book’, used to instruct young scribes in the correct forms of writing and grammar, may throw some light on an interesting analogy. It seems that fishing and snaring activities may have been viewed as pursuits a married man should avoid when unaccompanied by his wife:

“The dancing-girl said, “Go Au, and see to your wife. How bitterly she weeps for you! Because of your catching fish by night and your snaring fowl by day, she is constantly weeping for you.” (Book of Kemit)

Whether such pursuits were analogous for getting up to no good, we may never know. The scholar Réne van Halsem has yet another observation regarding fishing in the marsh imagery. He suggests we look more closely at the fish being speared. Egyptian artists were renowned masters in representing nature down to the fine details of individual species. By the New Kingdom, the tilapia fish often present in spearing imagery had developed an iconography representing regeneration. This is explained by the fact that the tilapia’s young hatch in the adult’s mouth, a process which may have appeared as spontaneous generation.

An ideal Eternity

Figure 25. Dog turning to look at owner, Tomb of Renni el Kab. Eighteenth Dynasty. Photograph courtesy of Osirisnet

It is tempting to consider idealised scenes of daily life, including the imagery of pet animals beneath chairs, as aspirational, or wishful thinking’. Just as one might wish to spend the afterlife with family and friends in beautiful outdoor settings, one might also desire the company of a much-loved pet there, too. Although we should avoid colouring the ancient past with emotional responses from the present, it is hard to view this unknown artist’s rendition of Renni’s dog as he looks back wistfully at his owner, without acknowledging an ancient appreciation of canine devotion [Figure 25].

An inscription which serves to illuminate a tomb owner’s thoughts as he passively observes the encoded imagery of his life surrounded by family, friends, and the beauty of nature reads, “Observing the marsh pools, fowl pools, back swamps, fishing and fowling, more beautiful to see than anything”. For a culture so invested in life, this was surely the ideal way to spend eternity [Figure 26].

Reflections of Eternity by Barbara O’Neill is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial License.

For some outstanding examples of animals represented in Egyptian relief and sculpture, see Dorothea Arnold’s “An Egyptian Bestiary”, free to download from this link, http://snipurl.com/27teva

Bibliography

Arnold, D., 1995 An Egyptian Bestiary’ in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Spring 1995

Baines, J., 1993, Symbolic Roles of Canine Figures on Early Monuments, Archéo-Nil, May 1993

David, R., 1998, Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, OUP

Der Manuelian, P., 1985 Two fragments of relief and a new model for the tomb of Montuemhet at Thebes, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 71

Fischer, H., 1961, A Supplement to Janssen’s List of Dogs’ Names, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 47, pp. 152-153

Ikhram, S., 2005 Divine Creatures, Cairo, AUC Press

Kanawati, N., 2001, The Tomb and Beyond, Warminster, Aris & Phillips

Lichtheim, M., 1973, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Vol. II, University of California Press

Masseti, M., and Bruner, E., 2009, The primates of the western Palaearctic, Journal of Anthropological Sciences, Vol. 87, pp. 33-91

Osborn, D., and Osbornova, J., 1998, The Mammals of Ancient Egypt, Warminster, Aris & Phillips

Piccione, P., 1990, The Historical Development of the Game of Senet and Its Significance for Egyptian Religion, University of Chicago

Reisner, G., 1936, The dog which was honored by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Robins, G., 1997, The Art of Ancient Egypt, London, British Museum Press

Robins, G., 1999, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 119

Samuel, D., 2009, Baking and Brewing in I. Shaw and P. Nicholson’s ‘Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology’, Cambridge University Press

Schorsch, D., and Frantz, J., 1997, A Tale of Two Kitties, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 16-29

Schulz, R., 2004, Dog missing his master. Reflections on an Old Kingdom tomb relief in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, M . Barta, ed The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology’.

Strandberg, A., 2009, The Gazelle in Ancient Egyptian Art, Image and Meaning, Upsala.

te Velde, H., 1980, A Few Remarks upon the Religious Significance of Animals in Ancient Egypt, Numen’, Vol. 27, pp. 76-82, Brill

Turner, D., and Bateson, P., 1998, The Domestic Cat: The Biology of its behaviour, Cambridge University Press

Van Halsem, R., 2005, The Iconography of Old Kingdom Elite Tombs, Ex Oriente Lux

Wente, E., 1930, Letters from ancient Egypt, translated by Edward F. Wente; edited by Edmund S. Meltzer, 1990, Scholar’s Press

Wilkinson, R., 1992, Reading Egyptian Art, Thames and Hudson

Wilkinson, R., 2003, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, Thames and Hudson

Websites

http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk

http://www.pyramidtextsonline.com/library.html

Image Credits – Used with Permission

Figure 1, Dog and monkey under chair, Tomb of Nikauisesi, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 2, Fifth Dynasty Offering Table Scene with ‘reed loaves’, Tomb of Ptahhotep, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 3, Eighteenth Dynasty Banquet Scene, Tomb of Nebamun, ©copyright The British Museum

Figure 4, Eighteenth Dynasty representation of a folding stool, Tomb of Userhat, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 5, Fourth Dynasty Tomb of Nefertiabet, Giza. Note the papyrus umbrels on the princesses’ ornate stool. This plant references fertility and regeneration.

Figure 6, Eighteenth Dynasty high-backed chair, Tomb of Menna. Photograph by Nacho Ares

Figure 7, Nineteenth Dynasty, Neferrenpet-Kenro playing Senet. Photograph by Nacho Ares.

Figure 8, L to R: scribal equipment, woven mirror-case, mirror and small monkey under the chairs of Userhat and Mutneferet, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 9, Fifth Dynasty, hounds with handler, Tomb of Ptahhotep, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 10, Twenty Fifth Dynasty, Tomb of Pabasa with dog ‘Hekenu’. Photograph by P. Gorgori

Figure 11, Fifth Dynasty, Tomb of Ty, Saqqara, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 12, Twelfth Dynasty Tomb of Djehutyhotep, Deir el Bersheh, copyright The British Museum

Figure 13, Fifth Dynasty Hunting Scene, dogs bringing down oryx and gazelle, Tomb of Ptahhotep, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 14, ‘bHn’ dog, Tomb of Nebamun, British Museum, Photograph by P. Gorgori

Figure 15, Middle Kingdom Tsm and bHn dogs, Tomb of Sarenput I, Aswan, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 16, Fifth Dynasty, Cattle Fording Scene, Tomb of Ty, Saqqara, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 17, Tomb of Ty, Saqqara, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 18, Fifth Dynasty, Tsm hound with calf, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photograph by P. Gorgori

Figure 19, Fourth Dynasty Tomb of Nerfermaat, Meidum, Carlsberg Glypotek

Figure 20, Monkey under chair of Userhat’s daughters, Eighteenth Dynasty copyright Osirisnet

Figure 21, Detail, Hunting in the Marshes, Tomb of Nebamun, copyright The British Museum

Figure 22, Cat under chair of the lady Tawy, Eighteenth Dynasty. Note the tethered cat’s efforts to reach his food, playfully (?) placed beyond his reach. Metropolitan Museum, Photograph by P. Gorgori

Figure 23, Inerkhau addresses his bA, Deir el Medina, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 24, Nakht and his wife in Fishing and Fowling in the Marshes Scene. Note that Nakht’s spear is missing, omitted in error by the artist, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 25, Dog turning to look back at his owner while senior officials prostrate themselves; Tomb of Renni, el-Kab, copyright Osirisnet

Figure 26, Nineteenth Dynasty Tomb of Pashed, TT3, copyright Osirisnet

By

By