By Howard Middleton-Jones.

Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 3, December 7th 2011.

First in an occasional series about Coptic heritage by Howard Middleton-Jones.

Introduction

The Middle East is a region of remarkable achievements, captured in literature from the 19th century onwards, often expressed in superlative terms. Readers will be familiar with the ‘Cradle of Civilisation’ (Ancient Mesopotamia, modern Iraq and Iran), and ‘The Land of The Pharaohs’ (Ancient Egypt). One of the area’s great achievements, however, is often overlooked. Egypt, the home of pyramids, temples and Tutankhamun, is also the birthplace of Orthodox Christianity. Alexandria remains the home see of His Holiness Pope Shenouda III.

Christianity was brought to Egypt by St. Mark the Apostle in the mid 1st century. This era, also known as the ‘Coptic Period’, produced some remarkable art and architecture, a plethora of literature and texts, (our modern book binding is based on the original method of Coptic binding) and its own language (in a number of Coptic dialects and regarded as the final stage of the Ancient Egyptian language). The Coptic culture also had its own calendar, based on the Ancient Egyptian calendar of the solar year. Yet despite all these remarkable achievements and accomplishments during this period, it is surprising how little most Egyptians and visitors to Egypt know of this period, and how unaware of the cultural heritage and issues surrounding the Coptic people in Egypt today.

The actual term ‘Copt’ and accompanying adjective ‘Coptic’ originate from the Arabic qibt, which itself is a corruption of the Greek term for the people of Egypt (Agyptos). The term also referred back to the ancient Hikaptah or the house of the ‘ka’ or spirit of Ptah, the temple of one of the great gods of Egypt. Following the Arab conquest of Egypt (AD 639-641) the Arab rulers utilised the term ‘Copt’ to designate the non-Arabic speaking and non Muslim Christian inhabitants of Egypt. Over time when the majority of the indigenous Egyptian people converted to Islam they ceased to be qibt. Today the term ‘Coptic’ refers to the Christian population of Egypt, said to be around 10 or 12% of the total population of Egypt. Thus the percentage of the Coptic population has now been completely reversed from what it was 1500 years ago, and today they are a minority, both in numbers and influence.

Figure 2. The monastery of St. Victor (Nagada region) and the remains of a monk’s cell. Monks often spent time living alone in these ‘cells’ made of mud brick, meditating and living an ascetic lifestyle. Copyright Howard Middleton-Jones

The ethnic and cultural background of the Coptic people appears to some to be quite complex, and much confusion surrounds the use of the term ‘Copt’ by scholars from a number of disciplines. In religious terms the term ‘Coptic’ today refers to the followers of the Egyptian Church (Coptic Orthodox), which broke off relations with Constantinople after the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451. It also applies to a minority of Christian Egyptians who have become Catholic and Protestant, belonging to each of the respective Coptic churches in that faith.

The Coptic Calendar

The Copts have their own calendar and being indigenous to Egypt it maintains cultural and ethnic ties to the Pharaonic and Ptolemaic eras. The calendar, often referred to as the ‘Alexandrian Calendar’, is based on the ancient Egyptian solar calendar and is regarded as the oldest in the world. The Coptic year is divided into 12 months of 30 days followed by five additional days called ‘epagomenai’. However, the Coptic year commences from the time that the Roman emperor, Diocletian, acquired the throne in AD 284. This date marks the beginning of the ‘Era of Martyrs’, where many thousands of Coptic Christians were executed because of their faith. The date is abbreviated as A.M. (anno martyrum) and so the Copts mark 29th August AD 284 as the beginning of their ‘history’. For example, the date of December 1st 2012, in the Coptic calendar would be the month of Hator (Hathor) day 21 year 1728 (2012 minus 284).

The Coptic new-year presently corresponds to 11th or 12th September of each year, depending if the year will be a leap year, while Christmas is presently celebrated on the day corresponding to January 7th of each year. The Gregorian calendar omits a leap year at the start of certain centuries, but the Coptic Calendar always observes leap years every four years, so the two calendars are asynchronous and by 2100 the Coptic Christmas will correspond to 8th January Gregorian.

The three seasons are again based on the ancient Egyptian agricultural seasons, the Nile-flood season, the sowing season and the harvest season. The construction of the High Dam at Aswan throughout 1960’s obviously changed the agricultural system but the traditional seasons are still respected.

Founding of the Coptic Church

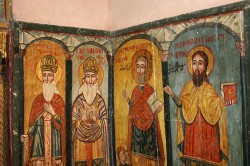

Figure 3. The Apostles St. Luke, St John, St Mathew and St. Mark in the Chapel of St. George at the Church of St. Mina Old Cairo . Copyright Howard Middleton-Jones

Whilst there are conflicting opinions regarding the origins of Christianity in Egypt, it is generally considered, according to Coptic tradition, that Mark the Evangelist (St. Mark) was the founder of the Coptic Church in Egypt in the middle of the 1st Century AD. In AD 68 the Pagans of Alexandria placed a rope around the neck of St. Mark and dragged him through the streets until he was dead. Up until AD 828 the relics of St. Mark were housed in Alexandria, until Merchant Venetians stole them taking them to Venice where a Basilica was constructed to house the relics. According to Coptic tradition, however, his head remained in Alexandria.

In 1968, after requests by the Coptic Pope (Cyril VI) some remains of the relics of St. Mark were returned to Egypt, and are now housed at the Cathedral of St. Mark in Abassiya Cairo.

St. Mark is regarded at the founder of the Patriarchate (of Alexander) and thus the first ‘Pope’, and since that time each successive Coptic Pope includes the full title reflecting this apostolic succession. The current Coptic Pope is His Holiness Pope Shenouda III, the 117th Pope of Alexandria, and as such his full title is His Holiness Pope Shenouda III, the 117th Pope of Alexandria and the Patriarchate of all Africa and the Holy Apostolic See of St. Mark the Evangelist of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.

The Holy Family in Egypt.

The Holy family in Egypt are vital to the psyche of the Copts as faith in the oral tradition is often valued more than literary evidence. Apparitions and miracles play a crucial role in the rise and continuity of the traditions of the flight of the Holy Family in Egypt. In addition, it is not only Christians who follow and seek blessings at the pilgrimage sites, but also Muslims who go there to seek healing.

The flight is only mentioned briefly in the Gospel of St Mathew 2. 13-23.

Churches and monastic settlements throughout Egypt mark most of the sites associated with the Holy Family, while Coptic painting and the production of icons and murals are also an integral part of the belief and ritual practice of the Coptic Church. The iconographic image of the flight has remained largely unchanged through the last 1500 years, that is, the depiction of the Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus riding a donkey with Joseph on foot. In addition, almost any depiction of the Virgin and Christ Child may be seen as having points of connection to the Holy Family’s trip thus transforming Egypt into a second Holy land.

It is not recorded where exactly or for how long the Family stayed in Egypt. As much of the details of this story are collated from the Coptic tradition and individual Coptic sites, one has to combine written sources with the local history and stories of each sacred geographical site to form a coherent view. Most of the sites associated with the flight reflect some form of tribulation overcome by the Holy Family, such as palm trees bowing down to offer dates, local wells springing forth and caves miraculously appearing to hide them. Thus, after each encounter (tree, well, cave and so on) the sites concerned were endowed with healing powers which became places of pilgrimage, marked by a church, monastery or convent, and usually dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and named Al-adhra.

Six of the 15 largest Christian ‘mulids’ (pilgrimage festivals) in Egypt are dedicated to the Virgin and all but one held at Holy Family sites. This is the Church of the Virgin at Zaytum, where the apparition of Mary appeared in 1968 where it was extensively witnessed and recorded. In addition to mulids, there is also a celebratory event called nahdas organised to commemorate the death or martyrdom of a Saint, usually taking place 3-15 days prior to the Saint’s actual day. The name in Arabic means ‘birthday’ but in the Coptic Church this refers to the day the Saint died, or the day they are reborn into everlasting life. These nahdas often turn into a mulid, the only difference being that nahdas are spiritual celebrations. To make a nahda is to make a vow, while a mulid is a tradition celebration.

Figure 5. Ceiling icon of Christ in the Church of St. Mina Old Cairo . Copyright Howard Middleton-Jones

Abu Al Makarim, a 13th Century writer, often mistakenly identified as Abu Salih the Armenian, in his survey of the Coptic Churches and Monasteries of Egypt, described many hundreds of Coptic sites many of which no longer survive. He comments that the reason why Egypt surpasses all other countries; “is the sojourn in this land of our Lord Jesus Christ, in the flesh with the Pure Lady Mary and the truthful old man Joseph the carpenter, by the command of God”.

Therefore, it may be inferred that the sacred geography of Christian Egypt reflects not only the passing of the Holy Family but the historical experience of the Copts.

Whilst many of these sites have now been lost to the desert sands, there are still a considerable number of Churches and monastic sites existing today. Many are in a ruinous state, but many have been carefully restored, including their unique art and architecture. A database project was instigated in 2007 (Middleton-Jones 2010) to collate all of these sites, including locations, photographs and references, providing one central resource for knowledge about Coptic heritage. This is a major on-going project and hopefully will contribute to current and future site restoration and preservation programmes.

Art and Architecture

Due to the fact that Coptic Christianity has regularly been in religious opposition to the faith of Egypt’s rulers, Coptic art and architecture have rarely enjoyed the benefit of imperial or royal patronage, and therefore lack the monumental grandeur of the ancient Egyptian temples or mosques of medieval Cairo. However, the unique Coptic wall paintings and icons within the monastic structures have a dignity and beauty of their own, so reflecting the faith and tenacity of the Coptic community. This introductory article cannot do full justice to the unique richness and quantity of Coptic art in Egypt, but a more in-depth article is planned for a later date.

The origins of the layout of Coptic Church can be said to go back to Ancient Egypt, this being reflected and shown in the temple plans where there is an outer courtyard and an inner hidden sanctuary. The Church also consists of an outer Narthex (porch) and later buildings show a sanctuary and screen (iconostasis).

Figure 7. The Coptic Church within the Basilica of the temple of Dendera. Copyright Howard Middleton-Jones

The Coptic monks were extremely good at ‘recycling’ materials and reconstructing Churches and Monastic sites from previously ruined sites, such as at ancient Egyptian temples. It is common therefore to observe stone blocks incorporated within the walls of Churches inscribed with hieroglyphic material. This is evidenced at the Red and White monasteries in the region of Akhmim Middle Egypt, and at the Greco-Roman Temple of Dendera. The basilica at Dendera demonstrates an excellent representative example of early Coptic Church architecture, where it possesses a nave with two aisles and a trefoil shaped sanctuary at the east end fronted by two columns which once supported an arch.

Figure 8. Archway in the Church at Dendera showing Christian decoration. Copyright Howard Middleton-Jones

Over the past few years there has actually been an increasing interest in the cultural heritage aspects of the early Coptic culture, with tour operators including a number of the more important sites on their itinerary. However, current events in Egypt have, unfortunately, prevented many tourists from visiting. Security issues, especially with respect to visiting Coptic sites, have been a major challenge. The other main challenge involved in visiting the Coptic sites is their physical locations, often in remote areas. Due to the recent Church bombings in Alexandria, Cairo and other locations, this has placed an incredible burden on the Coptic Church. Not only do they have to provide added security for the sites, in the form of additional armed security personnel and physical barricades around the Churches, but they are also dealing with issues of potential conflict with the more extreme Islamic fundamentalists, which in turn caused added concern and difficulty.

Figure 9. Qubbat el-Hawa Elephantine Aswan 6th Dynasty tombs of the Nobles with a 8th – 9th Century AD Coptic Church site constructed within and around the tombs. Copyright Howard Middleton-Jones

In the light of recent political events in Egypt, many tourists are now staying away from Egypt, which is unfortunate, especially for a country whose people rely so heavily on the tourist trade as a major part of their income. It is indeed sad to witness these events, especially in a country which is deeply steeped in historical culture of all periods, and even more so when political and religious differences impinge on one of the most unique and important cultures in ancient history.

Hopefully, 2012 will see a marked improvement in the political stabilisation and conditions for the general populace of Egypt, and tourists will once again be seen in large numbers up and down the Nile.

Bibliography

Evetts B.T.A and Butler A.J (eds) 1895 The Churches and Monasteries of Egypt and some neighbouring Countries. Attributed to Abu Salih the Armenian. Clarendon Press Oxford

Gabra. G (Ed) 2008 Historical Dictionary of the Coptic Church. The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Middleton-Jones 2010 The Coptic Monasteries Multi-Media Database Project in ‘Christianity and Monasticism in Upper Egypt Volume 2 – Nag Hammadi-Esna’ Eds Gabra G and Takla H.N. The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Credits

All photographs are the copyright of Howard Middleton-Jones

Biography

Howard Middleton-Jones is the tutor for the Archaeology and Coptic Studies programmes at the Department of Adult Continuing Education, Swansea University. Howard gained his degree in Ancient History and Classics at Swansea University and attended Oxford University where he undertook the Post Graduate Field Archaeology programme. He has been a corporate member (PIFA) of the Institute of Archaeology for over 15 years and is a regular traveller to Egypt presenting papers at the Coptic symposiums.

The Open Programme Coptic Studies Module at Swansea will be taught by the author, with dates beginning in January 2012 and each running for 10 weeks: The Coptic Period in Egypt: The Early Christian Period 1st Century – 7th Century; Post Arabic Coptic Egypt. 7th Century AD – Present Day, Archaeology Culture, Art and Architecture; and Coptic Thebes. Life, culture, sites and monuments in 2nd Century – 7th Century AD Thebes. For further details please email Howard Middleton-Jones: h.middleton-jones@swan.ac.uk.

http://www.ambilacuk.com/coptic/courses.html

By

By