O45.1: An Ancient Industrial Estate

Review by Kate Phizackerley.

Published on Egyptological, Magazine Reviews, Edition 3, 7th December 2011

Introduction

As described in the overview of the 2011 AWT Conference which I co-authored with Andrea Byrnes (see bottom of this review), Dr Paul Nicholson spoke about his excavation of the Amarna site designated O45.1, which was, for a time, used for the production of pottery, faience and glass. Previously the site had been a cemetery and by the end of the Amarna period had changed usage again to become what Nicholson described as a “casemate” site, although he didn’t say what this meant. [Andrea heard “casement” instead, although this is no clearer.] Nicholson mentioned these earlier and later usages in passing but spoke in detail only about the industrial phase.

O45.1

The site O45.1 lies in the main city alongside the main thoroughfare, about 200m SW of the Small Aten Temple, placing it a similar distance SSW of the Great Palace. Questioned about the closeness of a potentially noisy and smelly facility so close to the palace, Nicholson said it was probably a deliberate wish to keep a strategic resource under close oversight and Barry Kemp interjected to add that the prevailing wind would blow smoke and odours away from the palace.

Excavations by Nicholson revealed a number of small kilns and two larger furnaces. The area had been excavated previously by Flinders Petrie so Nicholson drew upon Petrie’s notes to supplement his findings. Nicholson showed some of the moulds found on the site, but Petrie had found very large numbers which he reburied in a cache which, in spite of a search, has not yet been relocated. No large workshop buildings were discovered but Nicholson reminded the room that the Egyptian climate is suited to working outside, so workshops may not have been required.

Pottery

Unsurprisingly, Nicholson talked first about the kilns that he identified as used for firing pottery, although he reported difficulty in precisely differentiating between kilns that had been used for firing pottery and those that had been used for the manufacture of faience. The kilns have clay floors overlying mud brick and walls consisting of a single layer of mud bricks, which he believed had come from an earlier demolished kiln. It is likely that kilns had a limited useful lifespan before replacement was necessary.

The evidence for pottery making is provided by finds of unfired pottery and some clay waste marked with scratchings from having been shaped on a wheel. Nicholson described how there has been some academic debate whether an Egyptian wheel was fast enough to throw pots (rather than being merely a turntable), but he reported an experimental study, in which it was shown that the speed needed was not as fast as had been believed. Hands-on experimental archaeology emerged as a trait of Nicholson’s methodology and throughout his lecture the emphasis was just as much on the practicalities of ancient Egyptian manufacturing as much as the archaeological insights provided by the site.

The segue into the next section was well handled by describing some of the finds of unfired pottery which included a mould for casting a faience ring …

Faience

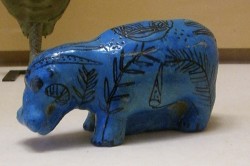

Nicholson could have made the mistake, made by some other speakers, and assumed that the members of the audience all had pre-existing knowledge. He avoided the trap by describing the composition of faience (see side bar) and the process for its manufacture. Lots of faience has been found and it is believed that Amarna was a significant manufacturing centre for faience.

Faience Composition (Nicholson)

|

The faience manufacturing method used at Amarna is one area in which Petrie was wrong. Petrie’s suggestion was that application glazing was used. Nicholson, however, has been able to demonstrate that an efflorescence method was used at Amarna. (He mentioned that we now know of a third production method, cementation, although this was not apparently used at Amarna.) Visitors to the Petrie Museum at University College London (UCL) can see faience moulds from Amarna, which are choked with faience paste accumulated after several firings. Faience moulds discovered include a Bes figure with tambourine and the name of the Aten. Clay pots used as bead mounts have also been found with some faience beads permanently stuck to the pot. Less certain is the use of certain shallow-lipped clay trays which bear an impression of textile and which Nicholson thinks were used for dipping.

Glass

Although faience is strongly associated with ancient Egypt and therefore resonated with the audience, Nicholson’s passion for O45.1 centres on the glass making carried out there, demonstrated both by his enthusiasm and the time he dedicated to the subject. Glass has a lower silica content (≈ 62% – 65%) than faience. I didn’t quite catch kiln allocation at O45.1, but Nicholson indicated that the largest two kilns (numbered 2 and 3) located in the centre of the site were used for glass making, and “kiln 5” probably not a kiln at all but an annealing hearth for pre-production, possibly of glass but the evidence is tentative. Other experts believe that kilns 2 and 3 were too large for glass making but Nicholson concluded his talk by discussing an experiment he and his team conducted. They constructed a replica kiln they and used it to successfully cast glass in a test firing on 12th September 1996. The experiment was largely faithful to ancient techniques and resources, other than in the fuel used. The modern reconstruction used pine and palm wood, but the Egyptians probably used acacia. They also used seaweed from Penarth beach as the alkali – the Egyptians probably used the plant Salsola kali (prickly glasswort). Indeed, our word alkali is a derivative of the Arabic al qaly, meaning “from kali”.

The interior temperature of the reconstructed kiln reached 1150ºC, a critical temperature at which unfired Nile bricks used for the kiln starts to vitrify, but after use the bricks lining the interior of the kiln are left in a fired state. (The faience kilns consist of just one layer of bricks, but the kilns used for glass making have several layers of brick.)

The teams ingot is reportedly chemically stable, containing few bubbles and with only a small amount of un-reacted (unfired) material. Demonstrating commendable balance, Nicholson accepted that the evidence for the use of kilns 2 and 3 to manufacture glass is relatively sparse. A few fragments of glass were found and the curvature of the walls suggests they were capped by a roof dome, which he said was consistent with a type of furnace known as a reverberating glass furnace, or reverberatory furnace. (He didn’t describe this, but subsequent study shows that the dome of a reverberatory furnace reflects the heat back down into the kiln chamber.)

Beyond experimental archaeology, which he obviously believes to be valuable, Nicholson’s excitement lay in the fritting process he believes was used as Amarna. Egyptian frit, like faience, is a non-clay ceramic and a precursor to glass in a two step manufacturing process. Nicholson recounted that Tuthmosis III is believed to have captured glassmakers from Kush / Mitani and brought them to Egypt to establish glass-making there. Like Chinese silk in later times, the method for making glass was a closely guarded secret. Nicholson speculated that the Amarnan glassmakers may have been producing glass ingots for export. Once cast as an ingot, glass can be re-melted and shaped in a relatively commonplace, low-tech process. The Uluburan shipwreck, a vessel which founded off the Turkish coast at about the same time, was carrying cobalt-blue and lavender glass ingots. Could, asked Nicholson, these have been cast at Amarna?

Metal

Metal production was quickly covered. There is no evidence of metal working at O45.1

Conclusion

There are no conclusions to be drawn about Nicholson’s material, as his lecture was presented without a conclusion. This is not a criticism. He gradually built interest, culminating with his report on the experimental firing. The lecture was both well-structured and presented very competently.

I confess that I wasn’t looking forwards to this lecture at all. I have worked on a large industrial site and in all honesty I find manufacturing rather dull. It is a tribute to Nicholson’s skill as a lecturer, his knowledge of the subject, and infectious passion, that I found his lecture quite the opposite of boring, indeed for me his lecture was one of the highlights of the day. Industry was a part of Amarna, and it was good that it was addressed in detail when lesser conferences might have restricted their coverage to religion and domestic matters.

About Dr Paul Nicholson

The AWT conference programme offered the following biography for Dr Paul Nicholson:

Dr Paul Nicholson studied archaeology at Sheffield University and was awarded his PhD in 1987. In 1983 he began working for Barry Kemp at Tell el-Amarna and from 1985 for David Jeffreys at Memphis. In the 1990s he co-directed work with Professor Harry Smith at the Sacred Animal Necropolis at Saqqara. He is currently working on the Dog Catacomb at Saqqara. He also directed the excavation at Amarna site O45.1 which is the subject of his lecture to AWT. He is author of several books including the British Museum Directory of Ancient Egypt (co-authored with Ian Shaw) and Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology (co-authored with Ian Shaw).

About the Conference

The 2011 Ancient World Tours Conference was held at UCL, London over the weekend of 3rd and 4th September and took Amarna as its theme. Nicholson was just one speaker from a high calibre platform which included prominent Egyptologists like Barry Kemp and Bill Manley, through to the respected scientific journalist Joanna Marchant.

Image Credits

Figure 1 – Egyptian Glass and Faience (Metropolitan Museum, New York) – Creative Commons non-commercial image by (Ancient Art http://www.flickr.com/photos/antiquitiesproject/) modified by Kate Phizackerley and released under a Creative Commons non-commercial attribution Licence v3.0

Figure 2 – Faience blue hippo, Creative Commons non-commercial licence from sarahstarkweather (http://www.flickr.com/photos/sarah1rene/)

Figure 3 – Model of Uluburun in Bodrum Museum, Creative Commons non-commercial licence from David J Lull, (http://www.flickr.com/photos/davidjlull/)

By

By