Review by Andrea Byrnes.

Published on Egyptological, Magazine Reviews, 7th December 2011.

Gifts of the Nile: Ancient Egyptian Faience

Edited by Florence Dunn Friedman.

Published by Thames and Hudson in association with the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 1998. 288 pages. 482 illustrations, 225 in colour.

Pages are 23cm wide x 30cm tall (a little larger than A4).

ISBN 0-911517-65-0.

Introduction

Faience (tjehenet) is a man-made non-clay ceramic, the main ingredient of which is silica (crushed quartz extracted from desert sand and other raw materials). Plasticity and stability are provided by the inclusion of lime and soda and it is cemented by firing. The process produces a bright white fabric, which reflects the glaze, giving it luminosity. The exterior colour is achieved using different minerals (for example, copper for the dominant blue and blue-green). It was used to create items from the very small, like amulets and items of jewellery, to statuettes, large vessels and bead dresses. It could be the exclusive material used to create an artefact, or it could make up one of many materials used in the decoration of an item. Faience items are often very beautiful.

Faience was celebrated in the exhibition “Gifts of the Nile, ” which was organized by The Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design in Cleveland (U.S.), where it opened in 1998 before it then travelled to the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth in Texas (U.S.). Published to accompany the exhibition, the book Gifts of the Nile brings together academic insights, an exhibition catalogue, and colour plates. This is a beautifully illustrated book about Egyptian faience, a remarkably luminous substance used to create artefacts and amulets from the Predynastic period onwards. Included are five articles by separate authors and a large selection of stunning photographs showing many of the items that were on display.

The opening article is written by the editor, Florence Dunn Friedman, who introduces the purpose of the exhibition and the book that supports it. The writers who contribute the remaining articles in the volume are experts in the field, are Robert Steven Bianchi, Diana Craig Patch , Peter Lacovara and Paul T. Nicholson.

Acknowledgements and a chronology of Egypt are followed by the articles, the plates, maps, an appendix, a glossary, the bibliography, photographic credits, a concordance and the index.

The Articles

All of the articles are accompanied by illustrations and black and white photographs.

The first of the five articles, Faience: The Brilliance of Eternity by Florence Dunn Friedman, explains the overall aim of the exhibition to “explore the meaning of faience within Egyptian culture, as well as to examine how it was made, and for – and by – whom It is also an exhibition intended for “the sheer pleasure of viewing beautiful works of art” (p.15). Friedman goes on to explain how the word faience has nothing to do with the Italian faience produced in Faenza, from which the term was derived. The rest of the article summarizes, in brief, some of the main features of faience production and its cultural role in Egypt, including the manufacturing process, its geographical distribution, the colours chosen, and how it was viewed in cultural and domestic terms. There is a useful nine-stage diagram showing the faience manufacturing process. She wraps up with an explanation of how the colour plates in the book are divided into groups to represent and explore different themes. She concludes: “Despite the marshalling of archaeological, textual and laboratory data, scholars may still hold differing opinions, so that not all interpretations offered in this volume will necessarily accord” (p.20). Some of the themes she outlines here are discussed in the remaining four articles.

In Symbols and Meanings, Robert Steven Bianchi takes a closer look at the cultural and ideological aspects of the mining of minerals, and the production and use of faience. His focus is entirely on the way in which the elite controlled and valued faience, which he makes explicit in the following statement: “[t]he Egyptian elite, eager to safeguard its position at all costs, developed a formal visual vocabulary that made its ideology manifest and incorporated into each element a coded message about whose invariant and universal significance was immediately obvious to the viewer” (p.22). Bianchi begins with sourcing and working of the raw materials, for which there is very little evidence from either texts or in the form of workshops. Instead, he suggests that there are good analogues in elite sculpture and metal smelting, suggesting that crafts were in general regulated by “cultic rite” and a “religiously sanctioned process” (p.23), that raw materials were sourced by teams under the king’s control from land under the control of the king, and that the production quality and the achievement of the craftsman was part of an item’s value. He looks at the Ancient Egyptian word for faience, tjehnet, the etymology of which relates to the words for luminosity and scintillation, and he explores how it was incorporated into the symbolic value of items and their association with specific deities, concepts and contexts – with particular reference to the “Brides of the Dead”. Bianchi assesses the meaning of faience when used in conjunction with various other materials, suggesting that combining minerals was an intention to symbolize ideas of creation (the primeval mound) and resurrection in the afterlife (Osiris in his “mineralized” form). He wraps up with a consideration of how Greek and Roman faience items relate to Dynastic examples before summarizing his conclusions.

Diana Craig Patch, in By Necessity or Design: Faience Use in Ancient Egypt, reviews the types of faience objects found in Egypt. She begins with a chronological overview, looking at its origins in the Predynastic when it was used for cultic objects, and the growth in its popularity after the Old Kingdom with a large range of artefact types produced in the Middle Kingdom, including funerary jewellery and an expansion of types in the New Kingdom with an increased use of mould technology. Her comments on the characteristics of faience (including malleability and ease of modelling) help to explain why it was so attractive to Egyptian craftsmen and purchasers. She addresses the question of why, when the raw materials of faience were inexpensive, faience objects were less common than objects made of comparable materials in the New Kingdom, looking at the ranking of individuls to see whether faience and status correlate. Her examination of faience in the tomb of Tutankhamun and other royal and non-royal tombs is fascinating, and her favoured explanation is that objects made of faience were “used for specific purposes consistent throughout the culture, regardless of socioeconomic class” (p.41). She looks in her next section at Amarna, observing that the same types of object are found in the settlement as in the tombs considered in the previous section. Finally, Patch lists her conclusions, the most interesting of which, perhaps, is her observation that faience was used “not because of its inexpensiveness [sic] or easy availability – that is in imitation of more precious substances – but because of its color and finish; the choice of faience was integral to the function of the finished product” (p.43), that function being ritual and amuletic.

Nubian Faience, by Peter Lacovara, is a short article that looks at the balance, through time, of imports and locally manufactured items. The earliest glazed material dates to c.3100 BC and although some items appear to have been imports others seem to have been manufactured locally although he says “[h]ow this Nubian glazed quartz was produced in the absence of a tradition of faience manufacture is unclear” (p.46). As one would expect, when faience manufacture grew in Egypt it became increasingly popular in Nubia. Lacovara explores when and where local manufacturing or Egyptian imports were dominant, looking particularly at frontier garrisons during the Egyptian Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom and, further south, at the Kerma area in the Middle Kingdom, First Intermediate Period and New Kingdoms. In the Classic Kerma period (1700-1550 BC) the greatest quantities of faience in Nubia are found, mainly in funerary chapels. Some imports were found whole, other items were assembled locally but made of broken imported sherds. Some had been manufactured locally, composed differently in terms of glaze and bodies from Egyptian wares. After Classic Kerma and the return of Egypt’s forces, faience quantities decreased, but items were still manufactured locally as well as imported. Lacovara says that glass apparently eclipsed faience in the Meroitic period.

Finally Paul T. Nicholson looks at Materials and Technology. The longest of the five articles, this is probably the most demanding, but Nicholson does an excellent job of breaking down the science and technology into digestible chunks, making the chemical composition of faience and the end to end process of its production perfectly easy to get to grips with. This is a significant achievement. After looking at the composition of faience, Nicholson looks at how Ancient Egyptian craftsmen coped with the fact that is much less plastic than pottery and can be temperamental when being worked. He provides a table to show how the methods of shaping faience changed over time, including hand working, moulding and throwing on a wheel. Glazing is described next, with three processes defined – efflorescence, cementation and application – with a useful diagram showing the processes graphically. The methods of decorating are considered next, and related materials are discussed briefly, including Egyptian blue frit, which is often confused with faience. Experiments in firing have informed Nicholson’s short section on how kilns were built and used. The biggest section is “Technology Through Time” which looks in detail at how the methods of making faience changed from the Predynastic to the post-New Kingdom periods. He looks at aspects like factory production, kilns, industry organization, job titles, material composition, shaping techniques and innovations. Nicholson does not provide any conclusions, but the article does not require them.

The Plates

This chapter displays lovely colour photographs showing many of the items displayed in the exhibition. The plates inform the reader about the full range of artefact types, styles and colours that were produced from all periods of Dynastic Egypt. They convey the colour and light of the original pieces.

The plates are divided into categories: Early Faience, Faience and Royal Life, Women’s Use And Female-Related Themes, Faience In Daily Life And Devotion, Funerary Uses of Faience and Materials and Technology.

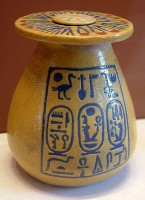

Some of the artefacts are given full pages and all are large so that details can be observed and hieroglyphs read. A variety of artefact types is represented, showing the full range of colours used, and many of the photographs show faience in combination with other materials. Some items have flat surfaces, others are highly sculpted. Although some of the items are glazed with a single colour, others use faience to make complex patterns and images in a variety of colours, the most subtle of which are often from the Amarna period.

The Catalogue

The catalogue follows the plates. Small black and white images are accompanied by descriptive text detailing the period, provenance (where known), current location and museum catalogue number. Some are accompanied by long descriptions about both the item itself and the greater context of the item.

Comment

The articles are all written by academics and each of the articles is aimed more at those who have a serious intellectual interest in faience and its cultural context than at the general public who might prefer something lighter and more generic.

Like all books composed of articles authored by different writers, it lacks the cohesion of a book assembled by a single author. At the same time, the format plays to the strengths of the individual authors, providing in-depth insights into each author’s areas of specialization.

There is little about the artistic merit of artefacts produced in faience. The book might have been improved with a chapter providing a broader overview of the artistic value of faience, using items from the exhibition to look at artistic motifs and jewellery.

The order in which the articles were published could have been more helpful. Nicholson’s chapter on technology and materials explains what faience actually is and gives an excellent description of why it was so luminous and how it was manufactured – this would have been helpful at the beginning, to inform readers of the nature of the product and help them to understand what went into making it and its key characteristics.

The photographs are big, bright and glossy, providing an idea of the full range of ways in which faience was used. Although this is not a coffee table volume, the photos will certainly charm those who are just as interested in the beauty of items as in the cultural and technological foundations of faience.

The combination of excellent articles, good quality colour photographs and a detailed catalogue have lead to a book that is amongst the more useful and attractive of those produced to accompany an exhibition focusing on a specific technology or art form, but most importantly it has a value of its own, independent of the exhibition. It balances, perfectly, detailed information and high visual appeal. Although the articles migh be aimed at an academic level that would not necessarily appeal to all exhibition visitors, it is an invaluable resource for anyone who wants access to high quality research and full references on the subject.

Conclusions

Back cover of Gifts of the Nile (click once to expand and then again to zoom in to read the text, which includes short author biographies)

One of the few books dedicated to a single Ancient Egyptian technology, Gifts of the Nile provides both well-informed articles looking at everything from the manufacture to meaning of faience, and provides a lovely visual record of the brightly coloured end-products, which provide a valuable supplement to the texts. The catalogue is a helpful record of the items included in the exhibition and upon which the articles are partially based.

In summary, it is a professionally produced, attractive and very useful book, offering high quality content for both academics and members of the public with a serious interest in the ways in which crafts were supplied, managed and used in Ancient Egypt.

Like many modern Egyptology books it already out of print, but at the time of writing it is widely available at remarkably good prices from online stores that sell second hand books.

If faience is your interest, it is certainly worth looking around for it because there are so few other books that look at the subject in such detail. For those who want to read more about faience see the chapter “Egyptian Faience” by Paul Nicholson and Edgar Peltenburg in Ancient Materials and Technology edited by Ian Shaw and Paul T. Nicholson, (Cambridge University Press 2000). A short but coherent summary is provided in Paul Nicholson’s Egyptian Faience and Glass (Shire Egyptology 1993). Others that may be of interest are Production Technology of Faience and Related Early Vitreous Materials by Andrew Shortland (Oxford University School of Archaeology 2008) and Brilliant Things for Akhenaten: The Production of Glass, Vitreous Materials and Pottery at Amarna Site 0.45.1 (Egypt Exploration Society 2007).

See also Kate Phizackerley’s review of Paul Nicholson’s lecture at the AWT Conference 2011, in the Magazine Edition 3 (December 2011), which included a discussion of Amarna faience. (Click on “faience” in the resource block below a link).

Credits

Faience tiles from the Step Pyramid at Saqqara. Saqqara Museum. Photograph by Andrea Byrnes.

Faience hippopotamus, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11-12, The Louvre. Photograph by Rama. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

Vase of Amenophis III and Tiy faience. The Louvre. By Guillaume Blanchard. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

Vase fragment bearing royal serekh of Aha, British Museum. By Captomondo. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

By

By