By Andrea Byrnes. Published on Egyptological, In Brief, on 13th January 2012

Introduction

In Joyce Tyldesley’s Judgement of the Pharaohs (2000), Tyldesley makes several references to an individual at Deir el-Medineh named Paneb, whom she describes evocatively as “the all round bad guy.” In this short article, I have brought together some of the misdemeanours outlined in a letter known as Papyrus Salt 124 for a closer look at this colourful character. This short article is heavily dependent on both Tyldesley’s book (which is highly recommended) and Jaroslav Cerny’s translation of, and comments on, Papyrus Salt 124. Unless otherwise stated the phrases in quotation marks are the translations of Papyrus Salt 124 by Cerny (1929).

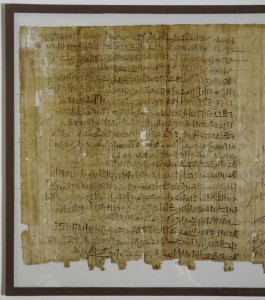

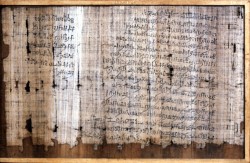

Papyrus Salt 124, now in the British Museum (collection number BM10055) , consists of three papyrus sheets, and dates to the late Nineteenth or early Twentieth Dynasty.

The papyrus is dedicated to complaints against Paneb. It comprises a letter by a worker named Amennakht to the Vizier at the time, probably Hori. The text indicates that this is probably a copy of a letter sent to the Vizier, rather than the original.

Amennakht is arguing for the removal of Paneb from the position of Chief of Workers on various grounds, mainly criminal, and it should be remembered that Amennakht, possibly hoping to secure the position for himself, was in no way an impartial observer of Paneb’s faults. However, if only half of the accusations were upheld, Paneb still seems like a fairly bad character.

The charges against Paneb

The papyrus opens with a statement of the grievance by Amennakht, a resident of the royal tomb workers’ village Deir el-Medineh. It was addressed to the Vizier in his role as a judge of legal issues. Amennakht was a worker in the village, the son of the former Chief Of Workers, named Nebnefer. Nebnefer’s position was inherited by Amennakht’s brother Neferhotep when their father was killed. At any one time there were two Chief of Workers at Deir el Medineh, responsible for the left and right parts of the valley, and the position usually passed to sons of the family. On the death of his brother, Amennakht probably felt that the position should default to him, but it was given instead to Paneb, who was unrelated to them, “although indeed it was not his place.”

The aggrieved Amennakht accuses Paneb of securing the position of Chief of Workers not, as one might have assumed and hoped, on merit but by bribing the vizier Preemheb with a gift consisting of five servants. Tyldesley remarks that Paneb was “unsuitable” for the job, and as one investigates Paneb’s career as told by Amennakht, this seems like something of an understatement. The rest of the letter goes on to indicate just how very unsuitable Paneb was for the position of Chief of Workers at Deir el-Medineh

During the weakening of authority at the end of the Nineteenth Dynasty the village was neglected by the authorities, and Paneb took full advantage of the situation. The first charge against him in the papyrus is that he was caught stealing from the tomb of Seti-Merenptah (Seti II), taking away with him numerous items including a chariot covering, oil, incense, a statuette and wines. Amennakht mentions that Paneb entered other tombs as well, stealing a goose from one and a bed from another: “He went down into the tomb of the workman Nakhtmin and stole the bed which was under him. He carried off the objects which one gives to a dead man and stole them.” Regarding the goose, Paneb claimed that it was not in his possession but Amennakht says that “they found it in his house.”

One slightly peculiar claim is that Paneb sat on the sarcophagus of Seti II. The appearance of this in such a formal legal document of complaint suggests that Paneb’s act is to be considered as an affront not only to that Pharaoh but to royalty in general.

Amennakht also accuses Paneb of using the village stone-workers to steal stone construction materials from Seti II’s tomb to use in his own tomb, thereby guilty both of theft and abusing his authority to divert workers from their state employment. Amennakht claims that Paneb was building columns for his personal tomb, and that he also stole tools “of the Pharaoh” to assist in this project. Paneb typically denied all charges concerning this theft claiming that he had not “upset a stone” in the vicinity of the tomb.

Another charge made against Paneb in the letter is that he was reported to the vizier for mistreating nine of his men by beating them. According to McDowell (1990), Paneb was punished but then made an official complaint against the vizier Amenmose to the Pharaoh Amenmesse, the result of which was that the vizier was removed from his position.

Amennahkt also accuses Paneb of threatening to kill Neferhotep after chasing him and cornering him (Neferhotep was Amennakht’s brother who then held the position Chief of Workers before Paneb). Although nothing appears to have come of the threat, the claim that Paneb came close to assaulting Neferhotep and intimidated him with death threats was obviously considered pertinent to the case.

The worst accusation is that of murder. Amennakht says: “it was he who killed those men that they might not bring message to the Pharaoh.”

Amennakht took a dim view not only of Paneb’s crimes and misdemeanours but his moral character too. Papyrus Salt 124 records that he robbed Iyemwaw of her garment before sleeping with her (it is unclear whether this was rape or not). He also, in Cerny’s words, “debauched” the lady Tuy, wife of Kenna, the lady Huenro, wife of Pendua, the lady Huenro again (or a different one), wife of Hesysenebef, and Huenro’s daughter Webkhet – as did Paneb’s son. Tyldesley makes the point that although adultery was not strictly illegal it was frowned upon and was dealt with by the community not the courts, and that its mention in this letter was a way of giving the court an idea of Penab’s general moral bankruptcy.

Papyrus Salt 124 does not have anything to say on the subject of how Paneb’s case was dealt with, whether he was found guilty and punished. However, Tyldesley says that the vizier Hori, for whom the letter was probably intended, was known for his harsh treatment of those who acted against the interests of the state. Cerny suggests that the punishment inflicted upon Paneb, if the vizier was impressed by the charges, “must have been heavy”.

Beyond Papyrus Salt 124

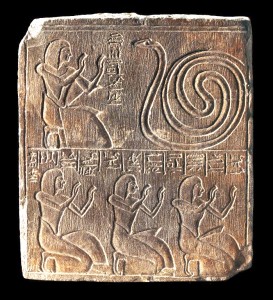

Paneb and sons worshiping Meretseger. British Museum stela 272. Copyright: Trustees of The British Museum

Although there is no ending, happy or otherwise, to Amennakht’s story, other details about Paneb’s life are available from other sources (his tomb, ostraca and stelae), which help to develop the picture.

Thanks to the identification of Paneb’s unfinished tomb at Deir el-Medineh (TT211), where some inscriptions have survived, and some small stelae that clearly identify Paneb, something is known about his family. His family members included a wife, Wabet, and sons and daughters. His grandfather was Kasa, whose tomb (shared with Penbuy) is TT10, and was a workman at the village. Paneb’s father Nefersenet was also a Deir el-Medineh workman, so it is clear that Paneb was born into the village and its life.

Cerny says that Paneb began his working life at Deir el-Medineh as a “man of the crew,” a simple workman. He is recorded in this role as early as year 66 of the reign of Ramesses II on two ostraca, one of which mentions his wife. Amennakht says that at a trial years before Paneb stated that if he caused the vizier to hear his name again he would be dismissed from office: “I shall become (again) stone-cutter, so said he,” suggesting that this was Paneb’s first position at the village.

Cerny estimates that Paneb was promoted into the role of Chief of Workers from at least the fifth year of the reign of Seti II. Paneb was responsible for the right side of the royal tombs, with his counterpart Hay responsible for the left side. Hay held that position in the time of Paneb’s predecessor Neferhotep and remained after Paneb’s successor Nekhenmut took over the office. A gap between Paneb leaving (or being removed from) the position and Nekhenmut becoming Chief of Workers may have been filled by one or more others. Bierbrier (1982, p.111) says that no Chief of Workers was a descendent of either Paneb or Neferhotep, so whatever the ruling, the Chief of Workers ceased to be passed to members of these particular families.

With respect to Paneb’s various infidelities, Tyldesley cites an ostracon that states that Huenro was divorced from Hesysenebef, and that her daughter Webkhet, who had (according to Amennakht) been involved with both Paneb and his son “went on to become a respectable married lady.”

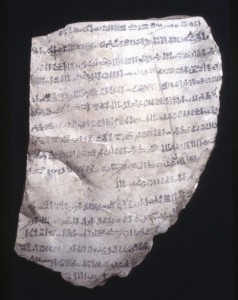

Ironically, as a senior member of the village, Paneb was on qenbet panels composed of community members that was convened to deal with cases brought against individuals at Deir el-Medineh. T.G.H James quotes two examples in his book Pharaoh’s People, one recorded on Ostracon 65930 (British Museum) and the other recorded on Ostracon 25556 (Cairo). In both cases Paneb was a senior member of the panel. Ostracon 65930 finds him judging the case of theft of a tool – a crime for which Amennakht holds Paneb guilty in Papyrus Salt 124.

A number of stelae survive, showing Paneb with members of his family, one of the finest is EA272 at the British Museum shows Paneb worshipping Meretseger, with three of his sons.

It is unknown if Paneb was buried in his tomb, which was empty and water-damaged. There is no evidence of the four columns for the construction of which he was accused of stealing both building materials and using royal workers. Cerny suggests that these columns would have been destined for the overlying chapel which has now vanished, and goes on to speculate that when promoted to Chief of Workers, Paneb may have started a new and more elaborate tomb, now lost or unidentified.

Finally, Tyldesley mentions that Paneb’s best known son, who was also worker at Deir el Medineh, seems to have inherited some of his father’s loose morals with regards to women, sleeping with at least one woman that Paneb had slept with before him!

Credits

Unless otherwise stated all photographs are copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Bibliography

For those who want to read more the bibliography is below, but there is also an excellent Wikipedia web page about Papyrus Salt 124 at:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papyrus_Salt_124 (last checked 11th January 2012)

Bedell, E.D. 1974

Criminal Law In the Egyptian Ramesside Period

Bierbrier, M.L. 1982

The Tomb-Builders of the Pharaohs

The American University in Cairo Press

Bierbrier, M.L. 1992

Ipuy in Cracow

Prace Archeologiczne, Z51

Bierbrier, M.L. 2000

Paneb Rehabilitated?

In R.J. Demaree and A. Egberts (eds)

Deir el-Medina in the Third Millenium AD, p.51-54.

Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.

British Museum Collection Database

Papyrus 10055 (last checked 11th January 2012)

British Museum Collection Database

Stela 272 (last checked 11th January 2012)

British Museum Collection Database

Ostracon 65930 (last checked 11th January 2012)

Cerny, J. 1929

Papyrus Salt 124 – (BM10055)

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 15 (1929)

Hall, E.S. 1986

The Pharaoh Smites His Enemies: A Comparative Study

Deutscher Kunstverlag

James, T.G.H. 1984, 2003

Pharaoh’s People. Scenes from Life in Imperial Egypt

Tauris Parke

McDowell, A.G. 1990

Jurisdiction in the Workmen’s Community of Deir el-Medina.

Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 1990.

Tyldesley, J. 2000

Judgement of the Pharaohs

Phoenix

Van Den Boorn, G.P.F. 1988

The Duties of the Vizier: Civil Administration in the Early New Kingdom

Routledge

By

By