Photos and commentary by Brian Alm.

Published on Egyptological, In Brief, on 18th January 2012

Introduction

The following short article provides a virtual tour of some of the items on show in the recent exhibition from the Oriental Institute Museum’s 2011 exhibit, Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization, at the University of Chicago.

The nine-month exhibit closed Dec. 31, 2011, but the accompanying 288-page catalogue, including nearly 150 pages of essays by 22 authorities on Predynastic Egypt, is available from the Oriental Institute, 1155 E. 58th St., Chicago, IL 60637, U.S.A.; (e-mail) OI-Museum@UChicago.edu; (Web site) OI.UChicago.edu; 773-702-9520 (Emily Teeter, ed., 2011. Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago).

The Exhibits

Two of the exhibit items, the Battlefield Palette and the small statue of Khasekhem, were on loan from the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, but the rest were from the Oriental Institute’s collection, much of which is on permanent display. The Oriental Institute specializes in the ancient cultures of the Middle East and Egypt; the museum is open year-round, closed Mondays and four holidays: January 1, July 4, Thanksgiving Day, December 25.

Pit burial.

The early Predynastic graves were simply oval pits, heaped up on the surface to symbolize the Primeval Mound and regeneration. This reconstruction of a typical burial in Naqada II, a permanent exhibit at the Oriental Institute Museum, shows the body in a fetal position, suggesting the second birth to come. At this time the dead were buried facing west, the realm of the dead. Already by now grave goods included food and drink, as well as personal possessions, valuables and objects of daily life for use in the world beyond. The dry desert climate naturally mummified bodies buried in the sand, but jackals remained a problem, so eventually the Egyptians sought more secure — and far more elaborate — final resting places, and also institutionalized the practice of artificial mummification — which was governed, ironically, by the jackal-headed god Anubis.

Palettes 1, 2, 3.

Palettes such as these, used to grind cosmetics, appear early in the Predynastic Period (5000-3100 BCE). Palette 1 is in the shape of a fish, a common motif for these items. Palette 2, from Naqada II (3800-3300 BCE), appears to suggest a boat made of papyrus with a cabin on top. Palette 3 (Naqada IIIb, 3100 BCE), is a beautifully stylized representation of a falcon. The Egyptians ground malachite to make green eye shadow and charcoal for the black kohl that accented their eyes. In keeping with the belief that the Afterlife would be a continuation of the present life, grave goods included these palettes, so the dead could appear at their best in Eternity.

Black-topped redware.

Black-topped redware (called “B ware”) dates back to the Badarian Period that preceded Naqada I and continued through Naqada II. Although there was a simple turning device available, there was no potter’s wheel until the late Old Kingdom; these vessels were made by coiling and building up slabs of clay, then shaping them manually and with simple tools, such as paddles.

Sequence dating 1.

Black-topped Redware, the earliest Predynastic pottery, was followed by white decoration on red, then buff-colored squat vessels with handle lugs, painted with geometric designs, and then vessels with wavy handles, classified as “W ware,” which was made of marl clay instead of Nile silt. These stylistic changes — in particular, the shift of Levantine-influenced W-ware handles from functional ledges to simply decorative wavy lines — led Flinders Petrie to develop the sequence dating system. By its type, color and decoration, pottery could be used as a foundation for stratigraphic dating. The chart displays a brief chronology of pottery development by type.

Sequence dating 2.

Here we see the historical progression in the later Naqada pottery: from left, a W-ware jug from Naqada IIc, 3400 BCE; two vases from Naqada IIIa2, 3200 BCE; a cylindrical vase from Naqada IIIb, 3100 BCE (here the W-ware style has now been reduced to a thin rope-like string around the top, as decoration); and a cylindical calcite tumbler from Dynasty 1, 3100 BCE.

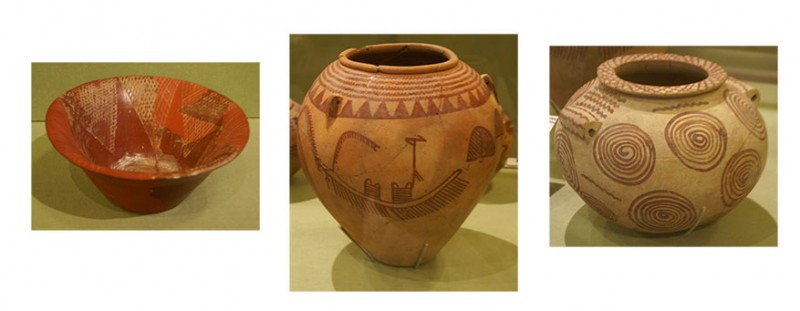

Painted vessel 1.

The burnished red coloring and white decoration characterize this bowl as very early pottery, identified as Naqada Ic, about 3700 BCE. In Petrie’s sequential dating nomenclature, it is called C-ware, for “white cross-lined pottery.”

Painted vessel 2.

Ideas find expression in pottery, evident in this Naqada II vessel, 3800-3300 BCE, whose decorations tell a story. Hieroglyphic writing would not come along until much later, but the symbols and representations inscribed on these vessels can be read to reveal meanings. The triangles are the cliffs along the Nile. The zigzag pattern on the aft cabin of the boat indicates the god Min, who protected people traveling in the desert and, as a fertility god, empowered male potency. The boat itself is shown to be a very large one, by its many oars.

Painted vessel 3.

This Naqada II (3800-3300 BCE) vessel may have been a jar whose lid was secured to the top by means of the pierced handles. The wavy lines, interspersed among the spirals, have been interpreted as representations of patterns in stone. Recreating natural things in art and architecture was a practice in Egypt even in these early times; later, the stone columns in temples replicated the bound bundles of papyrus that had been used in earlier times to support beams and lintels.

Jar with wavy handles 1.

Jars like this Naqada IIc vessel, from about 3400 BCE, were produced by the tens of thousands just for funerary use alone. The vast quantities of jars, both pottery and stone, that have been found in tombs show no sign of wear, so they were obviously intended only as grave goods.

Jar with wavy handles 2.

This jar was made by Egyptians in about 3400 BCE, but the wavy handles were copied from vessels imported from the Levant. According to exhibit coordinator Emily Teeter, the wavy handles “became increasingly abstracted until they were simplified to represent a rope.” (See “Sequence dating 2.”)

Beer jar.

This beer jar is typical of the coarse pottery of Naqada II (3800-3300 BCE), used for storing beer and baking bread — the two staples of the Egyptian diet from Predynastic times on. The production of this buff-colored “Rough ware,” made of Nile silt, proliferated in mid-Naqada II to serve the expanding bread and bear industries. Production on an industrial scale was an important factor in the development of the Egyptian state.

Naqada II-III jar.

This jar, produced sometime between 3800 and 3100 BCE, shows the exquisite craftsmanship and artistry that had developed by this early time. The stoneworking capabilities of the Egyptians — evident in this jar of diorite, an extremely hard stone — would be applied to monumental statuary a thousand years later.

Credits

All photographs by Brian Alm

Source

Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization, Emily Teeter, ed., 2011. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

For more on the relative dating of the Predynastic see:

A Beginner’s Guide to Dating the Predynastic -Part 1.

By

By