Published on Egyptological, Magazine Reviews, Edition 4, February 27th 2012.

Review by Andrea Byrnes

Judgement of the Pharaoh: Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt

By Joyce Tyldesley

A Phoenix Paperback

ISBN 075381278 9

199 pages. No illustrations. Four sides of black and white photographic plates

2000

Introduction

Joyce Tyldesley is the author of several excellent books about Ancient Egypt. With her husband, Egyptologist Steven Snape, she established Rutherford Press Ltd in 2004, created to publish books on Ancient Egypt which are both accessible and academically sound. At the time of writing she is a Senior Lecturer associated with the KNH Centre for Biomedical Egyptology, at Manchester University (UK).

In Judgement of the Pharaohs Tyldesley has tackled a subject that challenges the populist view of Ancient Egypt as a perfect world untroubled by social problems. Tyldesley begins by explaining how she described the idea for her new book to a colleague who said “Crime and punishment in ancient Egypt – surely there wasn’t any?” If an archaeological colleague was so quick to question that perfection of the Egyptian idyll, it is just as well that Tyldesley begins by assuring the reader that there was plenty of crime to be punished.

The book is aimed squarely at a non-expert, albeit inquiring reader. It deals with the complexities of Ancient Egyptian social mechanisms and morality, has strong academic foundations and uses both direct and indirect evidence to create a very coherent view of Egypt’s problems with crime. It is almost certain that most readers who pick up this book will know something about Ancient Egypt, but no prior knowledge is needed.

Chapter by Chapter

The book consists of a map of Egypt, a preface, introduction and 12 chapters, wrapping up with end notes, a chronological table, bibliography and index. Tyldesley comments early on that although endnotes and in-line references can interrupt the flow of a book she has provided numbered references to the Ancient Egyptian texts used, chapter by chapter, so that the reader can investigate further if required.

In the Introduction Tyldesley gives a short introduction to the different types and levels of crime and the forms of justice available. She gives an excellent overview of the types of direct and indirect evidence available for these (mostly indirect) and goes on to describe how, although Egypt’s social and political stability makes it possible to comment on 3000 years of history as a single topic, there are chronological differences in the range of data and the revelations that it supplies.

Chapter 1 (Maat and the King) introduces the religious and political framework within which justice existed and of which it was a conceptual part. Maat (cosmic order), the opposite of isfet (chaos), was the guiding theological principle of Egyptian life on earth. As a semi-divine being linking heaven and earth, the king was both part of maat and responsible for its maintenance in Egypt. Law and order, and failure to comply, come into the realm of maat and its violation, and was managed on behalf of the king by various administrative personnel. Tyldesley discusses some of the laws imposed at state level, focusing particularly on “exemption decrees,” supplements to state laws by individual kings. She looks at how these laws became more specific over time in terms of the nature of punishments (often the exact number and nature of physical reprisals) for particular crimes.

In Chapter 2 (The Vizier: Upholder of Justice) Tyldesley uses original New Kingdom texts to illustrate the role and duties of the Vizier. She looks briefly at how viziers were appointed from the Old Kingdom onwards, and how they operated in support of the king as a form of civil service, with teams of skilled administrators (scribes) supporting them in turn to dispense law and order at state and sometimes local levels. She looks at the role of prisons and touches on the subject of corvée labour. The Vizier is today a somewhat shadowy figure, and this comes across in this chapter.

Chapter 3 (Officers of the Law) looks at how officials who enforced the law were employed to act on behalf of the state’s interest rather than the needs of the community. Tyldesley describes the police (mainly the Medjay), and tax inspectors who could also enforce the law in order to protect the state’s wealth. Not even deities were exempt from tax: “Amen, during the New Kingdom . . . . was the most prolific of taxpayers,” with vast charges made upon the temple estates. Failure to deliver taxes could result in beatings or being used as corvee labour. Wronged private citizens had no such support and, when seeking justice, were “required to play the part of both detective and lawyer” (p.47). The community had to organize itself for the protection of its members against civil crime. Petty theft, as Tyldesley points out, was not the world of pickpockets and handbag snatchers, because without coinage most items worth stealing were not portable and were probably easily identifiable, and theft needs to be understood in this context.

In Chapter 4 (Crimes and Punishments) Tyldesley expands points that she touched on in the first three chapters to look in greater detail at the relationship between specific crimes and the very detailed penalties inflicted upon those who committed those particular crimes in the criminal courts and the less precise but consistent methods used in civil cases. Crimes against the state and monarchy were treated as most serious. Civil cases were more localized, often about the movement of property boundaries and stealing of cattle. Punishments included enforced financial reparation, labour, and physical mutilation (beatings, cuts and amputations) as well as, in extreme cases only, execution. Physical abuse was also used as a tool of interrogation. Many moral crimes were considered beneath the interests of the court and were dealt with by the families or communities involved. Tyldesley looks at the rise of crime in response to increasing population and socio-economic pressures in the Nile Valley during the New Kingdom.

Chapter 5, (Loss of Liberty) looks at the ways in which personal freedoms were taken away as a form of punishment. The most common of these was the assignment of those found guilty to temporary or permanent corvée labour, and the loss of status that went with it. Although slavery was not a form of judicial punishment, Tyldesley covers the subject of bonded workers in this chapter. She talks quite extensively about Egypt’s relationships, diplomatic and military, with foreign neighbours to the west, south and northwest. Prisoners of war were considered to be guilty of crimes against the state, and civilians in the conquered lands were also considered fair game. New skills were appreciated and their incorporation into the economy was valuable to Egypt.

Chapter 6 (Regicide: The Ultimate Rebellion) considers three different attempts to assassinate the king. Records of such cases are expected to be rare because it was not in the interest of the Egyptian state to record such attacks: “To admit that the king was human, and vulnerable, was to call into question the entire premise of divine rule” (p.90). Three records, however, survive. Details of an Old Kingdom plot are a little vague, but documents survive for the plots against Amenemhat I (who was successfully murdered) and Ramesses III (who died at around that time but whether due to the attempted murder or old age is unknown). Tyldesley provides some essential context for the cases discussed, a fascinating insight into royal family arrangements – the way in which wives were accumulated, princesses disposed of in marriage, heirs were decided upon, how younger brothers or heirs fared, and how these protected royal stability and royal succession. The potential temptation to tamper with the line of succession is highlighted by Tyldesley: “at times of dynastic uncertainty the combination of ambitious sons and pushy mothers in close proximity could prove dangerous” (p.93). She goes on to discuss the cases in detail, putting each into their appropriate political and economic context.

Chapter 7 (Tutankhamen: A Murder Mystery) provides an overview the evidence for the death of Tutankhamen by foul play. Tyldesley was writing in 2000, some time before the most recent examination of the king’s remains, when the only internal data available was from x-rays taken in 1968 and 1978. It is inevitable, therefore, that this chapter is somewhat outdated. Her arguments are good, however, she provides a useful analysis of the data then available and makes an excellent point about how the idea that Tutankhamun was murdered was accepted so easily: “by constantly referring to Tuankhamen as the ‘boy-king’ we are perhaps conditioning ourselves to think of his as an unusually early, even suspicious demise” (p.103). Her analysis of the political, religious and social context for the reign of Tutankhamun and those who succeeded him is typically articulate and helpful.

Chapter 8 (The Second Oldest Profession) looks exclusively at robbing the deceased. As usual, Tyldesley puts the matter into context, explaining provisioning for the afterlife and how this changed over time, the types of grave goods buried with different levels of the elite and the sort of temptation offered by the knowledge of rich tombs to those willing to break the taboos against robbing the dead. A number of crimes were committed – from the robbery itself, to those who turned blind eyes. Tyldesley traces opportunities for robbing the dead from the moment that they landed on the embalming table. She discusses how tomb builders attempted to protect burials using physical, administrative and supernatural devices, but how tomb robbing became prolific.

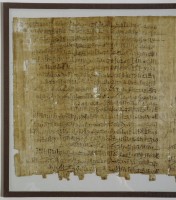

In Chapter 9 (Robbers of the West Bank) she develops further the theme of the previous chapter. She starts off by looking at the relationships between the villagers of the isolated Deir el Medineh and the authorities that managed it, describing the special conditions within the village and how the community responded to times of stress. Under the hardships of Ramesses IV to Ramesses XI, the period from which the Tomb Robbery Papyri (judicial records) survive, robbery of the Valley of the Kings reached crisis point. The papyri record how the robbers broke into tombs, what they stole, how they spent their ill-gotten gains, who they bribed along the way, and what punishments were handed out by the criminal courts in the name of the king. Tyldesley does an excellent job of drawing out the facts from individual documents to find patterns and draw general conclusions about how tomb robber gangs operated. Some of the documents give a vivid idea of how rich the rewards were, even given the risk of severe penalties for being caught.

Chapter 10 (The Villager and the Oracle) turns away from crimes committed against the state and instead looks at the petty misdemeanours committed in Deir el Medineh, where quarrels and disagreements, breaches of contract and minor thefts were all recorded on ostraca and papyri. Tyldesley looks at the disputes that could be settled locally and those which needed the intervention of outside authorities. She introduces the kenbet, a type of court convened for the purposes of resolving problems that individuals were unable to resolve themselves and looks at the sort of issues it was expected to handle and how it operated. When all else failed, the local oracle was consulted and Tyldesley describes how this was achieved, giving examples where the outcomes of such consultations are known. It was clearly a last resort: “The verdicts almost always coincided with local opinion . . . Certainly, it was very hard to appeal against the oracle’s public decision” (p.150).

Chapter 11 (Sex Crimes) is less sordid than one might expect, partially due to a more open attitude to fertility and sexual reproduction in Egypt, and a less formal attitude to marriage. Seduction and adultery are discussed, and were clearly disapproved of, reflecting badly on the moral standing of an individual. Rape and wife beatings are rarely documented so are discussed only briefly. Similarly cases of sex crimes against men are even less well documented, although whilst homosexuality was not a crime, “neither was it expected to be a pleasure” (p.163) and male rape was considered a way of emasculating a man and was not regarded lightly.

Chapter 12 (The Last Judgement) looks at the afterlife. In theory there should be no escape from the all-knowing deities, but Egyptian funerary texts provided the deceased with spells and guides with which to safely conduct their way through the challenges of the underworld. For Egyptologists they provide a very useful guide to which acts and attitudes offended Ancient Egyptian morality. Tyldesley also looks at the relationship between the living and the dead, and the extent to which the living believed that the living could intercede on their behalf or interfere with their affairs. Finally she looks at damnatio memoriae, the deliberate removal of the names of the dead from their monuments and other records. Much of the damnatio memoriae has little to do with crime and punishment except, perhaps, in the case of Akhenaten whose heretic ideas could be termed crime against the gods and who was known by later kings as “the great criminal” (p.174).

Following the last chapter there are Notes (end notes referring to the numbers against quoted paragraphs in the text, each listed under the chapter heading); a Chronological Table (showing years BC, dynastic periods and historical events); the Bibliography and the Index.

Overview

The entire subject of crime and punishment is set within the context of Egyptian social structure, theological belief and its core morality. The definition of crime is quite wide ranging, including criminal acts against the state, civil acts against other members of the community and having the gall not to accept Egypt’s military dominance in foreign lands.

Following an introduction that introduces the reader to the basic ideas to be explored and the nature of the evidence available, the first few chapters look at the roles involved in administering the law, starting with the Pharaoh and working down through the Vizier in chapter 2 and officers of the law in chapter 3. She then goes on to look at general crimes and punishments before looking at specific crimes against the state and communities, wrapping up with a look at how the deceased could be judged by the deities in the afterlife or punished by the living.

The impression that comes across is that whilst justice was incorporated into ideas of maat, for all practical purposes its job was to support the upper echelons. Lower ranks were entitled to represent themselves to the Vizier and seek rulings and redress, but were given no help in doing so.

Evaluation

There is an awful lot of good to be said of this book.

Tyldesley does an excellent job of setting crime and justice within the framework of Egyptian morality religious belief, social organization and the administrative machine. Although the subject of the book is explicitly crime and punishment, it would make a very good introduction for readers wanting to know about Egyptian morality, social and administrative structures, and how the larger working class community was, in general, served by (or not served by) the state machine.

She approaches the topic logically from the top down, starting with the concept of maat and the king, and drilling down into the ways in which Egypt was organized and how moral standards were perceived and dealt with, focusing on specific examples of crimes, how they were addressed and the punishments that were deemed appropriate, using case studies to illustrate the points she makes.

Her use of individual case studies helps to bring the subject to life, providing frequent windows into life as it was lived, with some fascinating facts and statistics offered. At the same time, it would be easy to become hopelessly involved in each of the individual stories but whilst Tyldesley is very good at sharing an individual’s tale with the reader, she always shows how each of the excerpts from these stories contributes to the body of evidence about her topic. Tyldesley approach is always to provide a kinks-and-all version of Ancient Egypt, not to provide a smoothed out vanilla version that might be easier to digest but which would be misleading due to being unrepresentative of all of the available data. Some of the individual cases are puzzling, in that they do not seem to conform to the usual pattern. Tyldesley never avoids these exceptions. Her approach positions the book as academically rigorous, whilst never becoming tedious.

Tyldesley uses all the data that is available. Her task would probably have been easier if she had confined herself to the New Kingdom and later, but she is at pains to include information, where available, from the Early Dynastic onwards.

Throughout the book Tyldesley provides contextual information for the non-expert, always informing in an articulate and friendly way, never either talking down to the reader or becoming too technical.

It is very difficult to find a downside.

I only observed one obvious omission. Perhaps surprisingly, prostitution is not mentioned in the chapter Sex Crimes, and whilst it may be that brothels were entirely legal and that single women selling their services in return for food or goods were not reviled, these questions are left unanswered.

Some readers might be disappointed that there is an emphasis on New Kingdom and Late Period material, but that cannot be a criticism of the book because there is a dearth of information about the subject before the New Kingdom and even less before the Middle Kingdom. In spite of these challenges, Tyldesley includes information from earlier periods whenever possible.

The inhabitants of Deir el-Medineh are used as near analogues for ordinary people – unfortunately the truly ordinary villagers of Egypt, being illiterate, not only left no records of their own but probably only rarely had the sort of grievances that gave them access to courts where records of their complaints would have been taken, if they had access to any system of justice at all. Whilst it is understandable that Deir el-Medineh is the closest that she could get to ordinary people, the workers’ village residents were not ordinary and she does not go on to suggest any mechanisms by which the ordinary people might have managed their affairs unless we are to believe, which seems unlikely, that they enjoyed any of the privileges that the workers at Deir el-Medineh had access to. Perhaps the Oracle was their only recourse.

In some chapters there are passages which would perhaps have belonged better elsewhere – for example the subject of corvee labour and the penalties for avoidance were dealt with in Chapter 2 (the Vizier), which seemed to be an odd place for it to be handled.

One might argue, at a push, that in dealing with subjects like slavery and the extent of Egypt’s diplomatic relationships with other Mediterranean countries, the role of the deceased in the life of the living and damnatio memoriae she goes slightly off topic.

Finally, this is not a picture book. Over two pages (four sides) in the centre of the book there is a set of black and white photographs, but these images provide little assistance to the reader who would prefer more illustration.

Conclusion

The subtitle of Judgement of the Pharaohs (Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt) talks about criminality and the measures taken to prevent the crime being repeated, deterrents to the criminal and the would-be criminal alike. But the book itself is about the morality of Egypt, tolerance and justice, and fundamental beliefs about right and wrong. As with so many societies there are different levels of security and protection against criminality and violations are dealt with by different levels of organization and institutions. The wealthy have more protection, more to lose, and a much greater level of state machinery to deal with criminal incursions into their world; the poor have much less to lose but whilst their loss will be harder to replace, they are poorly represented by the state and must fall back on their wits, community support, informal courts, more formal applications to higher officials and, as a last resort, the oracle. Crimes were just as diverse as they are in most modern societies, involving just the same amount of avarice, risk-taking, aiding and abetting and the turning of blind eyes. The greater the reward, the greater the risk, and in extreme cases wrong-doers could receive amputations or be sentenced to painful deaths.

By the end of the book Tyldesley has successfully deconstructed the image of an idyllic Egypt without crime, punishment, dispute or pain, making it altogether more realistic, and thereby allowing the reader to step into a familiar world where large crimes and small misdemeanours are judged and punished according to the scale of the crime and the importance of the person against whom it was perpetrated.

Tyldesley has a specific audience in mind and writes for it consistently and with great skill. She writes engagingly, is articulate and never talks down to her readership or assumes a level of knowledge that they might not have – a very difficult balance to strike, and one she does with ease, elegance and often gentle humour. This is one of a series of intelligent and serious books for the knowledge-seeking public by the author, and Tyldesley has yet again done a marvellous job.

As well as being a good introduction to Egyptian crime and punishment, this would serve as a useful primer to those wishing to get a good insight into the functionality of Egyptian society at all levels.

In short, this book is much recommended.

Credits

All photographs by Andrea Byrnes unless otherwise stated.

By

By