By Rosalind Park. Published on Egyptological, In Brief, on 31st May 2012 (addendum added 8th July 2012).

In the 1st century BC, the pragmatic Roman orator, Cicero (De Natura Deorum 2, 2) felt that in his educated and informed age, “those inventions of the imagination” ought to be put aside. For he enquired: “Who believes that the Hippocentaurus or the Chimaera ever existed”?

Known from the Classical Period, the chimaera was a three-formed zoomorphic fire-breathing being of divine origin. Art work featuring this mythical creature first appears on proto-Corinthian pottery from around 670 BC. The first written account occurs in the Homeric writings, and other accounts endure to the time of a mocking yarn in the 2nd century AD novel of Apuleius, “The Golden Ass”: “Pegasus leapt upward as high as heaven in his fear of being bitten by the fire-breathing Chimaera”. The legends vary – but in essence, for our interest, she mated with her brother, and produced the Sphinx. Her protagonist was the hero Bellerophon who rose up in the sky on the flying-horse Pegasus to slay her. Astronomers will inform you that, as a Spring rising constellation, Pegasus has the distinctive feature of a Great Square. That the early Egyptians were well aware of this constellation’s identification (in their terms) is another essay for a future time!

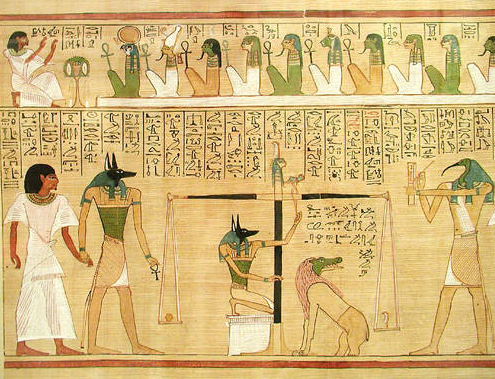

Ammit, the fourth figure from the left, in the Weighing of Heart ceremony. Photograph by Jon Bodsworth

As definitions go, Egypt had her own trisomatus monster in the form of Ammit – a fear-inducing being who lived in the Hall of Judgement. The heart of a deceased person was removed and rested on the scales of Maat. If the heart were judged evil and thus unworthy to embrace the Afterlife, the beast would immediately devour it. The funerary iconography of Ammit, represented in the artwork accompanying Spells from the Book of the Dead papyri, came into prominence in 19th Dynasty (1295 – 1186 BC), and was presumably invented by the high priests under the auspice of the reigning pharaoh. In these vignettes Ammit is depicted with a crocodile head, the body of a lion (or lioness), and the rear quarters of the hippopotamus. At the level of mere mortals during life, the nightmarish thought of placement in a small compartment with a hungry crocodile, lion and angry hippo, would be enough to trigger a heart attack – so the anticipation, after death, of an encounter with the 3 predators rolled into one creature, was not a good scenario to imagine! To most Egyptology researchers, Ammit is taken at face value: a scary monster with the epithet “Great of Death” who pre-warned of the wages of sin during life. Would Ammit scare mighty pharaoh? Ammit’s Hall of Justice domain was also called the ‘Hall of Two Truths’, which begs the question of “what is the other truth”?

It is often remarked that Ammit played no part in temples, nor was worship heeded to her despite the fact she was made up of components from New Kingdom worshipped entities, namely Sobek the crocodile, Ruti the double lion and Tauret the hippo. Contemporaneous with the 19th Dynasty new funerary images and rules of behaviour in the After-life literature, there were the marvellous vaulted astronomical ceilings in the Theban tombs of some of the pharaohs. Most splendid is probably the burial chamber ceiling of Seti I (KV17). Near the midline of the northern night sky are representations of Egyptian constellations and planets. Possibly a collaborator in the actual inventor of Ammit to keep his subjects god-fearing, Seti’s soul was on another mission, higher up. As befitting his kingly rank, the semi-divine Horus king would soar, and he had his flight plan mapped out! Lying in his alabaster sarcophagus, Seti could look up and see Horus the Red (planet Mars) in the king’s own sign of the Lion covered with stars (constellation Leo), Egypt’s “dragon” – the crocodile (Lunar Node), and looming large and upright, the Hippo goddess (the circumpolar constellation Cepheus). Thus is Seti’s journey marked – along the Ecliptic, through the destiny portal of where the Moon’s path crossed the Sun’s path (Nodal point), past Pegasus’s square and those other rising & setting stars that the Greeks gave heroes names to, and into the realm of the circumpolar Imperishable Stars.

The above, albeit fantastic, journey of Seti’s soul taking off to the stars above would have been totally appreciated in the Hellenistic period. Consider the last known datable image of the ‘Weighing of the Heart’ scene in a Roman period tomb. If the reader has no access to Herbert Winlock’s 1908 photographs of el-Muzzawaka, there is a representative image in George Hart’s book (1990: 21). The Dakhla Oasis tomb of the priest Padiosir Petosiris depicts an Egyptian styled zodiac and constellations on the ceiling. In the tomb’s inner chamber, a fresco of the Egyptian now fire-breathing Chimaera, Ammit, together with Osiris and Thoth. The ancient Egyptians maintained that Thoth was the arch-inventor of astronomy, and in this scene he stands behind Ammit counting notches on a palm branch. Clement of Alexandria (active in Egypt c. 150 – 215 AD) states that the notched palm was the insignia of the astrologer. Ammit is still recognisable despite losing the hippo back legs but having acquired two Maat feathers (of truth) upon her head. She is elevated on a door-way dais to be at the same eye-level of Osiris and, as an offering, is regurgitating hearts into a bucket of fire.

Addendum

The first recorded image of Ammit that can be identified is an unconvential vignette pained on leather. It was apparently attached to the late 18th Dynasty Book of the Dead papyrus belonging to the general Nakht. This protype of the monster-being pays no heed to Canon of Proportion rules which were applied in later representations. The image Nakht had to contemplate was a fairly naturalist open-jawed crocodile head coloured blue/gree, merged with a tawny wild mane, front paws and middle body of a lion, with a red coloured stubby rear-end and feet of a hippopotamus.

To see the image and find references to previous work: see John Taylor (2010)p. 220 in the British Museum catalogue “Journey through the afterlife – Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead”. Also available in the British Museum’s website at: http://bit.ly/NQCtb2 (click on the image to enlarge it and see more detail).

By

By