By Janet Robinson. Published on Egyptological, In Brief, 31st May 2012.

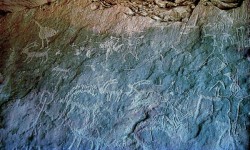

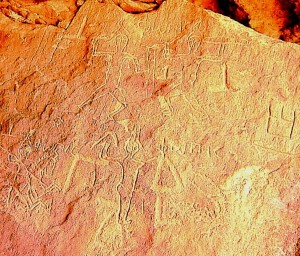

In the transition to Late Antiquity, an undercurrent of vernacular culture across the Roman Empire was beginning to reassert its voice, as people on the margins of society grew in confidence. Many people were illiterate, or at least were only able to write their own name. So how can we be sure when and how this happened? One way is to listen to the voices of local people and ordinary travellers, as they took their rest in the shade. [Figure 1 – to see the full sized images in this article please click on the small image] There are, of course, extant papyri which offer elite views of the Empire. But even the most private of records – a graffito – is a record, a cameo event, with a story to tell. It was of significance to its writer and therefore may be of consequence to us. [Figure 2 ]

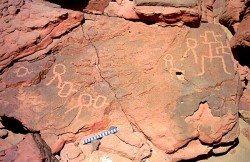

Travellers inscribed their names in Greek, Latin and other characters on rocks along the main routes to ports, quarries and mines in the Egyptian Eastern Desert. There are many of these graffiti messages and signatures. Some provided dates for their visit and the purpose of travel, while others are probably tribal signs. [Figure 3 ] The Egyptian Eastern Desert was heavily used at various times before the construction of the Suez Canal.

Later travellers exploited Roman wells and cisterns wherever possible. There were Muslim pilgrims, for example, on their way to and from Mecca. Records show that during the Napoleonic War the British Army dug wells such as Bir Ingleezi near Quseir, to facilitate travellers journeying from India to Cairo. Throughout all these ages the Eastern Desert was home to varying numbers of resident Bedu tribespeople. Never was it as busy, however, as it was during Roman times. [Figure 4 ]

A Romano-Egyptian called Phopis

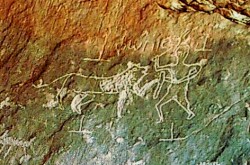

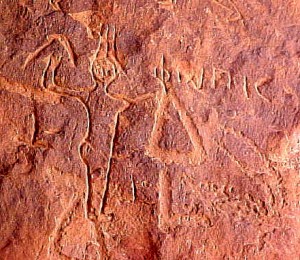

Phopis seems unusual. He was an Egyptian resting well away from the Roman military roads. There is no apparent reason for his presence at Hans Winkler Site 21, a small rock-shelter in upper Wadi Qash, where he engraved his name and drew some fascinating little pictures. [Figure 5] There are other even more ancient drawings at the site and plenty of tribal marks from various periods. Even though Wadi Qash became a pilgrim and British military route, nobody appears to have noticed Phopis. Perhaps he was overlooked simply because many of the graffiti sites are small and hard to see in the strong desert glare. The place was eventually located in the 1930s and published as Site 21 by Hans Winkler who at that time was in the desert looking for visible proof of predynastic and early dynastic activity. Phopis was obviously much later in antiquity, but despite this, Winkler was intrigued and published the name, description, and site photographs.

“The cave-like shelter is unique. Man in Phrygian cap fighting a lion with sword and shield, man in Phrygian cap on horseback in the attitude of St George, two men in Phrygian caps fighting each other with sword and shield. Min carved by the same artist. Every drawing is accompanied by the word Φωφις.” Hans Winkler 1938:6-7

In January 1999 archaeologists working near Wadi Qash looked for Site 21, which had not been mentioned since Winkler’s death in World War II. They went up the wadi as far as the well Bir Qash without success, though by chance they recorded another signature, “Kronios”, not seen by Winkler. They also found the signature of Apolloskephalas (Apollos son of Kephalas) across the wadi from Phopis. [Figure 6] The team eventually found Phopis and published him in French in the Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale (BIFAO 99) and in English in the Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum (SEG). The French publications are invaluable for research. However, much of what they have written appears inconsistent or careless as, for example, in the quote below in SEG which the authors lift from Winkler without citation.

“Rock-cut graffiti in a cave-like shelter on an alternative route south of the principal road from Koptos to Myos Hormos. Edd. Pr. H. Cuvigny, A Bülow-Jacobsen, BIAO 99 (1999) … … 2329: 174/175 nos. 84-88. Signatures. Five similar graffiti accompanying drawings incised on the rock (man wearing Phrygian cap fighting a lion with sword and shield; man wearing Phrygian cap on horseback, two men wearing Phrygian caps fighting each other with sword and shield; Min): Φώπιc” SEG Vol. XLIX 1999 pp.706-7

What do we know about the name Phopis?

The name Phopis (Fwpis) is an unaspirated version of Phophis (Fwfis), an ancient Egyptian name attested as Φωφις in the Demotic Namenbuch (DNB). [Figure 7] The hieroglyphic equivalent is Pȝ-ḥf – snake. Phopis’s handwriting indicates that he is most likely to have been in the Eastern Desert (Roger Bagnal pers.com.) in the first or second century AD. This period fits in with what is known about Roman activity in the area, but trying to achieve more precise dating is a problem. There are few clues in the pictures except perhaps the presence of the ancient Egyptian ithyphallic god Min. [Figure 8] However, by the second century AD there was a general decline in his worship, even though the god had been assimilated as Pan into the Graeco-Roman pantheon. Min/Pan seems to have been challenged by Alexandrian deities and disappeared during the transition into Late Antiquity. From this it could be concluded that that Phopis was a first century traveller. Or it could be a later anachronism and Phopis was just old-fashioned.

| Name | Greek | Egyptian | Bibliography | |||||||

| Phopis | trans-literation variant of: |

|

Pȝ-ḥf |

|

A useful resource is the English-language internet portal Trismegistos, which lists information gleaned from papyrological records, allowing researchers to begin locating the activities of various groups of people living and working in Roman Egypt. It should not be assumed that this site is only of use to Greek and Roman specialists. Names have long histories and may be little changed until Christian and Muslim times. Finding individuals in scholarly literature has hitherto been an extremely arduous task, involving visits to specialist libraries such as those of the Egypt Exploration Society and the Institute of Classical Studies. Even Trismegistos has its limitations in only looking at papyri, and does not appear to contain the many names inscribed on pottery ostraca and rock surfaces. In Trismegistos, for example, there is no mention of Phopis (Fwpis), though Phophis (Fwfis) is listed. It may therefore be assumed that the name, as spelled at Wadi Qash site 2329 (Winkler 21), is unknown to the Trismegistos Graeco-Roman specialists, and that it may not as yet have been brought to their attention. Phopis seems to be the only person of this name-variant and is therefore unique – as indicated by Hans Winkler. In the case of Phophis – the root name, however, Trismegistos has uncovered fifty-four examples and offers a list of documents in which the name is attested. There are also two graphs. The geographical chart shows the topographical spread of the name saying that it occurs in Thebes, Gebelain, Elephantine and Edfu but not, apparently, in the Nile Delta. The chronological chart reveals that the name Phophis seems to have been most popular from the first century BC to the first century AD.

The evidence strongly indicates that Phopis was an Egyptian with a local name. All we know is what he chose to reveal through his inscribed name and pictures. He may have been a military man or a merchant. As he rested off the guarded roads he could well have been avoiding paying his taxes. Of course individuals would have travelled between Roman quarries such as Mons Porphyrites to the north of Site 21 and the gold mines further south. By selecting Greek characters to write his name Phopis has added his voice to the history of Egypt in the Roman Empire.

Select Bibliography

Bagnall, R. (1993) Egypt in Late Antiquity ch. 7

“Languages, Literature and Ethnicity”

Brown, P. The World of Late Antiquity CE 150–750 (1971)

“Part Two: Divergent Legacies “

Garnsey, P. & Humfress, C. (2001) The Evolution of the Late Antique World

Heather, P.J. (1994) Literacy and Power in the Migration Period’, in A. Bowman

& G. Woolf (eds.), Literacy and Power in the Ancient World

Jones, A.H.M. (1964) The Later Roman Empire, Ch. 24: “Education and Culture”

Jones, A.H.M. (1966) The Decline of the Ancient World

Image Credits

Photos all copyright Paul Robinson

By

By