Published in Egyptological In Brief, November 2012. By Kate Phizackerley

Those who know me will be unsurprised that when I reveal I have been intending to write something about Egyptian mathematics for some time. Barbara O’Neill kindly sent me a link to an open learning section on the Open University website, drawing on material prepared by Joyce Tyldesley for her students: http://openlearn.open.ac.uk/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=397149§ion=1.1

The material quotes opposing views of Arnold Buffum Chase and Gerald James Toomer:

The Rhind and Moscow papyri are handbooks for the scribe, giving model examples of how to do things which were a part of his everyday tasks.… The sheer difficulties of calculation with such a crude numeral system and primitive methods effectively prevented any advance or interest in developing the science for its own sake. It served the needs of everyday life …., and that was enough. – G. J. Toomer.

A careful study of the Rhind Papyrus convinced me several years ago that this work is not a mere selection of practical problems especially useful to determine land values, and that the Egyptians were not a nation of shopkeepers, interested only in that which they could use. Rather I believe that they studied mathematics and other subjects for their own sakes. – A. B. Chace.

It then poses the following question for the student:

Do you now feel able lo [sic] form a view on which, if either, of these judgements on Egyptian mathematics is the better justified?

A model answer is given in section 1.1.3. While this has some merit, I find myself in disagreement to some of the basic premises. Rather better is the conclusion of the module itself:

What this exercise has also shown is that the endeavour to understand past mathematics naturally leads to forming judgements about it, in much the same way as art history and criticism are cognate activities. There is a disappointment in the reaction of some historians that a civilisation favoured by the gods in so many ways did not contribute more advanced mathematics. There was perhaps no need for more sophisticated mathematical investigation, nor any perception of such a possibility.

Firstly, it seems unfair to say that Egyptian mathematics did not have a significant contribution to more advanced mathematics. We do not have full records from some Copper and Bronze Age civilisations but the Egyptians and Babylonians were the first cultures to recognise the existence of fractions of a number. Today this might seem unremarkable but in primitive societies all numbers were cardinal integers, a representation of the number of cows in a pen, fish in a basket or people in a group. Numbers were direct representations of a physical count. Fractions – or more explicitly shares in the Egyptian way of things – are perhaps the very first abstract mathematical concept. Half a person or a third of a cow are largely meaningless in physical terms, but the concept that five fish might be split into three equal parts each of which would contain one fish and a fraction changes pure counting into mathematics. It is, in a very true sense, the foundation of advanced mathematics which relies on abstraction of concepts from the real world within a number system and system of logic. Of course, modern mathematics plays with alternative number systems and logical frameworks, but I suggest that the essence of mathematics is stepping away from real world counting.

A fairer question then might be to ask why our mathematics seems to be so different to Egyptian mathematics. This question is inherent in the OU material. I don’t however see such big differences. It is true that the Egyptians used reciprocals rather than fractions so that 3/8 would instead be written as 1/4 + 1/8. To us this seems cumbersome, for instance 2/17 becomes 1/12 + 1/51 + 1/68. Try 2/17 on a modern calculator however and the answer is 0.117647058823529… with the digits actually stretching to infinity. The Egyptian fractions may seem cumbersome but they do accurately represent the answer to the question of 2 divided by 17 in a way which is impossible in modern decimal notation. Does this mean that modern decimal notation is inferior to Egyptian mathematics? While 1/12 + 1/51 + 1/68 is more cumbrous than 2/17 it is still more concise than the infinite decimal fraction, or arguably even less cumbersome than a decimal like 0.1176470588235294.

But, you argue, “I have a sense of the size of 0.1176470588235294 but not of 1/12 + 1/51 + 1/68” Therein lies the answer. Those working with a number system regularly develop an intuition about things like size which is alien to those unaccustomed to that system. For all we know, an Egyptian scribe might well have had the same intuitively feel about numbers represented in their sum of parts fractions to our own modern sense of numbers. Of course, ability varies from person to person and there is no reason to believe that all Egyptians were comfortable with mathematics any more than people are today. Some people struggle with numbers, for others they just seem easy.

The OU material describes Egyptian mathematical technique as a “method of systematic ‘trial and error’”. At first glance this may also seem a primitive approach but again I disagree. Many modern computer algorithms are structure trial and error to home in on an answer. Moreover, while many non-mathematicians use a single method for multiplication or division, those more comfortable with numbers are likely to use a variety of techniques depending on the sum required. For instance, if asked to multiply 14 x 16 the sum I do in my head is 152 – 12 = 224 rather than a more traditional multiplication. The Egyptian approach based on doubling is one of the many approaches I might use. It’s not always the best method, but then neither is any other method.

Conclusion

While some people look at Egyptian mathematics and see only its differences to modern representations of numbers and calculation techniques, I see instead the foundation of modern mathematics. In moving beyond counting of physical objects we might say that the Egyptians actually invented mathematics. Their mathematics was not highly advanced – it was inherently practical in nature – but they started the world down the path which leads to modern mathematical ideas and techniques.

Modern academic papers refer only to Egyptian practitioners as scribes. Perhaps we should better recognise their contribution and call them mathematicians.

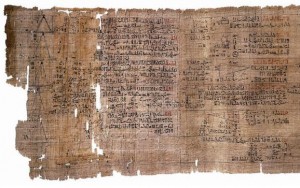

Images – public domain images sourced from WikiMedia Commons

By

By