By Garry Beuk. Published in Egyptological, Magazine Edition 8, 18th April 2013

Introduction

Figure 1. Labib Habachi, as shown on the cover of Jill Kamil’s biography “Labib Habachi: The Life and Legacy of an Egyptologist”

The story of Labib Habachi was predictable (figure 1). For centuries Egyptians suffered from the prejudicial views of foreigners arriving in their country. Some came in search of treasure, others in pursuit of knowledge and many simply to pass time because they had the wealth to do so. Half-hearted efforts were made by a few to train Egyptians as excavators, such as when a University was opened in 1869 in Bulaq. Lacking support and adequate funding it proved unsuccessful, closing its doors in less than five years.

Gaston Maspero, director of the Antiquities Service best defined the prevailing feeling of the times by continually denying excavation permits to Egyptians. He defended his actions by stating “Egyptians are only interested in finding treasure and are not motivated by scientific passion.” (Thomas, 2007)

In this article I will show how Habachi overcame adversity and discrimination from some of the most unlikely of sources, rising to take his place alongside the great Egyptologists of his era.

His Early Life

Labib Habachi was born on April 18th, 1906 in the village of Salamun in Middle Egypt (Figure 2). Described by Habachi as the “coldest place in Egypt”, Salamun is located between Mansoura and the waterway Bahr al Saghir. His father, Ibrahim Habachi was a Christian merchant supporting his family by bottling and selling honey and converting the honeycombs to candles for sale to the Coptic Church. Little is known of his mother Mauna; Habachi, her fourth son rarely spoke of her except to say that she had a hard time, having given birth to and caring for a total of 12 children.

For unknown reasons, but likely financial, Habachi was sent to live with an older married sister at her family farm when he was only 18 months old. Here he witnessed the transient life style of poor migrant workers, people he built solid relationships with and whom he related to throughout his entire life.

Life in Rural Egypt was dangerous, unlike modern times there were no inoculations. Refuse dumps and congested canals caused cholera and dysentery to be widespread. Habachi faced the constant threat of exposure to diseases such as conjunctivitis, typhoid, malaria, bilharziasis and ankylostoma. During the summer of 1907, in a country whose population was estimated at twelve million, an astounding three thousand children alone died every month. One might say that surviving early childhood was Habachi’s first major life achievement.

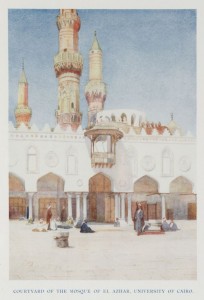

Although not residing with him, Habachi’s father was still very much in control. He directed his son in law to send Habachi to a Quranic school called a Kuttab. Here Habachi was instructed by a teacher known as a fiqi. The fiqi, who received extensive training at al-Azhar University (Figure 3), combined education and regimented discipline in the class itinerary. The Instruction was intense, focusing on basic fundamentals and far superior to what most children living in the country received.

At the age of six Habachi was next enrolled in a private Coptic school in Mansoura. The education was not tailored to students for their academic progression as most eventually dropped out to farm on their families land. Lacking structure and discipline Habachi’s grades suffered and his father, fearing for his future, sent him to live with his brother Ibrahim, a teacher in Cairo.

Ibrahim tutored Habachi for a year and then, recognizing his brother’s potential, enrolled him in a Maronite School. Established by missionaries in the eighteenth century the Maronite School was rooted in tradition and based on Eastern Christian Church fundamentals. In addition to basic studies the instruction included lessons in French and English. The instructors took discipline to extreme measures including corporal punishment for students not meeting the required standards. It is the Maronite School and its austere monks that Habachi first credits with halting his academic demise, stating that they were “responsible for the growth of my character”.

A Degree – But No Job

Later, after successfully graduating from Maronite in 1923, Habachi attended Fuad I University, presently known as Cairo University (Figure 4), to study mathematics. Whilst he was a very dedicated and successful student, he greatly disliked mathematics and the intense competition amongst the 150 students in the department.

Habachi’s father had envisioned him becoming a teacher like his brother, a well respected and good paying profession. However, Habachi had other ambitions; he had heard that a new Department of Egyptology run by prominent European instructors had been created. After much deliberation he considered requesting a transfer, but first he had to convince his father that the move was in his best interest. His father was not at all supportive of his plan; Habachi stated his father “was bewildered, he refused to listen to me” (Kamil, 2007). He could not understand why his son would give up a promising career for what was an un-established profession, especially for Egyptians. Habachi was relentless, finally convincing his father and officially transferring. In the class Habachi found his true calling; he felt a sense of pride and belonging working with his classmates. Inspired by the beauty and magnificence of his ancestors’ monuments Habachi received exceptional grades, graduating with a BA in Egyptology in 1928.

Habachi’s expectations were great; all the others in his graduating class were promptly assigned positions within the Antiquities Service or the Cairo Museum. Having been born in Egypt and doing so well at the University, surely a position would be forthcoming. Months passed by without an offer and Habachi appealed to Selim Hassan (1887-1961) (Figure 5), the professor at the University in charge of making appointments to open positions. Hassan responded to Habachi’s inquiries by simply referring to a candidates “good character” as being essential for appointment to coveted positions. Habachi was left to wonder if he would ever be given the opportunity to rise above his humble origins.

1928 – 1942- Long Road to Promotion

Personal tragedy struck Habachi when his father died in 1928. Never having seen his son acquire success in a field he was skeptical about to begin with, he had remained vocal in his disappointment up until his death. Habachi had little choice other than to wait patiently for news of an appointment; in fact he waited for over two years before one was finally made in 1930. Although as qualified for a position as his peers, the department was run by distinguished Europeans and available positions went to them first. When the decision of an appointment came, it proved to be a very minor position as an itinerant inspector with the Department of Antiquities.

The job took Habachi to many posts in Egypt, resulting in his having to be constantly on the move. He was responsible for 500 kilometers on both banks of the Nile, from Armant which is south of Luxor to Adidnan on the Sudanese border. He often travelled between the first and second cataracts gaining extensive knowledge of Nubia. Habachi, although under a great deal of stress made the most of his situation and later credited it with giving him the skills to become an experienced excavator. He cited that unlike his contemporaries he had the opportunity to learn “dirt archaeology” from some of the more experienced Egyptologists, such as Guy Brunton who instructed him whilst in Middle Egypt on how to record items in situ. This important practice of studying objects in their natural or original position assists excavators in gaining a more accurate picture of how an object or structure was used by a society and at this time it was not being taught in the classroom setting.

It is refreshing to see Habachi’s openness when he reflects back on this time period, acknowledging that he lacked the necessary commitment to his position. Habachi admits that he was more interested in visiting with colleagues and friends, drinking, joking and playing cards. This “party” mentality likely played a significant part in stalling his career. He missed important opportunities to exhibit his skills, including when famed British Egyptologist Walter Emery (Figure 6) made the major discovery of a royal burial of the king of the Nobodai tribe in Nubia, one which Habachi should have been present at, but was not. Summing up his first appointment as an inspector, Habachi grimly states “I see the certificate that provided me the necessary credentials for the position did not imbue me with enthusiasm” (Kamil, 2007).

Although he may have lacked the initial dedication, Habachi was certainly not unproductive. His understanding of the class based system, and how it related modern Egyptians to their ancient counterparts endeared him to his countrymen. Villagers trusted him, far more than they did his foreign colleagues and they kept him informed of potentially important artifacts as they turned up. For example, villagers of Qasr al-Deir reported to Habachi that a large statue of a camel had been unearthed in their village. They were certain that the ancient artifact was responsible for the deaths of numerous family members including newborns. The villagers ardently begged Habachi to immediately remove the statue. Upon investigating and excavating the area he found several small artifacts but no sign of the mysterious camel statue. Regardless, many years later upon returning to the village the residents recalled Habachis efforts and credited him for the fact that the families had experienced fewer deaths and many healthy births.

Habachi was a positive influence on the youth as well, encouraging children in Mansoura to properly report their discovery of exquisite granite blocks from the Temple of Isis. He later rewarded them, and encouraged their literary development with a valuable gift of books for their efforts.

Habachi was instructed, as were so many of his European counterparts, by the great William Flinders Petrie, whom had been granted a concession to dig on the eastern bank of the Nile between Asyut and Sohag. Habachi refined his knowledge of field archaeology and how to record objects in situ from the Father of Archaeology. Much like Petrie, Habachi refused to blindly accept conventional thinking. His theories, although based on sound evidence, occasionally resulted in unintentional controversy as they often conflicted with the accepted “expert” opinions of his peers. For example, he meticulously pieced together evidence disproving the long held belief that blocks from the Temple of Sais, dedicated to the goddess Neith, had been transported and reused in Alexandria. With a sense of purpose Habachi tirelessly travelled the Nile and found that the blocks had in fact been floated on the Nile, ultimately being used in Rosetta. He discovered that most of the houses and mosques from the end of the 16th century to the start of the 19th century had been at least partially constructed with blocks procured from Sais. He found additional blocks scattered in locations such as Dibi, Foua and al-Nahhariya, which are located on an old bend on the Rosetta side of the Nile.

Early in his career Habachi proposed the hypothesis that Tell el-Dabá in the Eastern Delta was the Hyksos capital. This was in direct contrast to the opinion by respected scholar Pierre Montet that Tanis (Figure 7) was the Hyksos capital. It was not until the 1980’s that Habachi found vindication when his opinion was confirmed by the renowned Austrian Egyptologist Manfred Bietak. It was now acknowledged that Tanis had been built from pillaged material and considered a secondary site, inhabited when the true capital of Avaris at Tell el-Dabá had been abandoned. This forced relocation occurred when the branch of the Nile that Tell el-Dabá was constructed on filled with silt and ancient attempts at dredging it proved unsuccessful.

Over fifteen years passed, during which Habachi was continuously overlooked for promotion and transferred no less than fifteen times. He again gained invaluable experience working with notable excavators such as Henri Chevrier at Karnak, Jean Capart at al-Kab and his Egyptian counterpart Zaki Saad at Helwan. In addition, he had the opportunity to work with Howard Carter in 1932 towards the end of Carter’s excavation of the Tomb of Tutankhamen. Habachi had been in charge of transporting the final forty cartons of artifacts from the tomb to Rex Engelbach, curator of the Cairo Museum. He recollected many years later that as the train rolled to a stop he met Engelbach, whom immediately requested the list of artifacts transported. Habachi was literally shaking with fear at discovering that he had left the packing slip that Carter had stressed was so important, in Luxor. Engelbach turned out to be extremely cordial about the incident and Habachi had found an ally to whom he would turn for professional consultation throughout his career. As for the historic Carter, Habachi’s brief and candid portrayal of him stated that; “He was meticulous in his work, possessive about the tomb, and extremely arrogant.”(Kamil, 2007)

Habachi’s first serious publication took place in 1937 when French Egyptologist Henri Gauthier accepted his report on the Fayum and it appeared in French in the Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte (ASAE). The report detailed Habachi’s transcription of fourteen columns attributed to Amenemhet III that William Petrie had discovered near the modern town of Kiman Faris. Habachi carried on where Petrie had left off, describing the structure in detail. A pavement of red granite and doors made of gold and silver brought new life, even if only in our imaginations, to a building which had long ago crumbled to dirt.

The Antiquities Department rewarded Habachi for his efforts in the Fayum by sponsoring his first professional trip abroad, to Greece. Habachi spent three and a half months in Greece, studying in the Museum of Athens. Upon his return to Egypt Habachi found his path to advancement once again blocked. Interestingly, much of the resistance was from a seemingly unlikely source, his Egyptian peer Selim Hassan. Hassan had studied under the great Egyptian excavator Ahmed Kanal and had found rapid advancement through the Department of Antiquities. He became the first Egyptian professor at the University of Cairo in 1928 and after graduating from Vienna University in 1935 was promoted to Deputy Director of the Antiquities Service. Throughout his career he would continually prevent Habachi from advancing in his own career. He had been the driving force preventing Habachi from being granted an initial assignment and this behavior continued through the 1960s, when he blocked Habachi from working on the Nubia Salvage Operation. It is difficult to comprehend the motivation behind Hassan’s behavior, why a successful Egyptian would not back the career of another countryman struggling for recognition. Likely, we need only look at the European Edwardian class system and the influence it had on the Egyptian social elite to find the answer.

Habachi suffered from a stigma that in many ways lives on in the present day, to be successful you have to come from, or marry into a successful family. Having been born to a relatively unknown rural Coptic family there was no place for him in the upper echelons of a society looking to emulate what it perceived as the success of their European benefactors. Simply put, in advancement opportunities, regardless of his education, talent and dedication Habachi faced a nearly insurmountable challenge. When competing with peers whom, due to birthright, fared better socially Habachi had a distinct disadvantage. Undeterred by this social stigma Habachi pressed on, spending the years of World War II recording and repairing damage done by vandals to temples and tombs.

1943 – 1945 – Success in Tell Basta

In 1943 Habachi was called upon to investigate in Tell Basta (Ancient Bubastis) due to the start of the construction of a military road through the site to connect Port Said with Alexandria. His findings halted the construction and resulted in a comprehensive report on The Temple of Bastet. The report brought much needed exposure to the problem of antiquities being stripped from the site and the ensuing destruction to the temple itself. It also led to the mandated protection of the temple and Habachi was granted first rights to excavate and document the ruins. His excavation of the surrounding area uncovered a fantastic find, a relief of Old Kingdom Pharaoh Pepi I and detailed four sided pillars still standing in situ. Habachi had discovered the ka-temple of Pepi I (Figure 8), the earliest known example of a ka-temple that had yet been found. He also unearthed the remains of a Roman temple and just to the north of the main temple a 20th Dynasty family tomb. The subsequent report to the Department of Antiquities in 1944 resulted in the publication of his award winning book entitled Tell Basta in 1957.

1946 – Excavations at Elephantine Island

In 1946 Habachi received his first major position when he was appointed Chief Inspector of Antiquities in Upper Egypt. Stationed in Luxor he was responsible for sites stretching from Qena in the North to Aswan in the South.

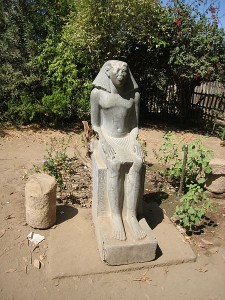

It was not long before Habachi was transferred to Aswan where his attention was soon drawn to Elephantine Island (Figure 9). In ancient times Elephantine, known as Yebu to the Egyptians, bordered Egypt and Nubia. It was heavily used in river trade leaving a wide array of antiquities for modern excavators. In a store house Habachi inspected statues that had been discovered by fallaha (peasant farmers) digging for sabakh, a fertilizer that is naturally derived from deteriorated ruins. The site had been partially excavated over a three week period by Egyptian archaeologist, Edouard Ghazouli in October of 1932. Ghazouli’s finds, high quality life size statues (Figure 10), all from the Middle Kingdom, fascinated Habachi. The fact that many of them were inscribed and devoted to a man named Heqaib caused him to question if the partially excavated sanctuary could hold more artifacts and perhaps even clues to the identity of what appeared to be a highly revered individual. First, funding needed to be secured to take on the expansive excavation and Habachi devised a plan to obtain it. The Restoration Committee was an Egyptian Institution within the Ministry of Awqaf that on an annual basis chose excavations to receive funding. At the conclusion of their tour and prior to making a final funding decision, they traditionally had a meal in Aswan. In Habachi’s current position he had the unique opportunity as host of the dinner to present his case to the committee in an informal setting.

Habachi knew that convincing the committee to allocate the required funds, an exceptional challenge, was his only hope to excavate. He planned an elaborate dinner and, playing upon the committee’s national pride in Egyptian excavators, was able to convince the group to visit the storeroom to view the long forgotten statues. Habachi was a brilliant speaker when focused on a topic and the committee was enchanted with him, leaving Aswan with their promise of funding. Excavation began on what became the passion and later the curse of his professional career, the Sanctuary of Heqaib (Figure 11), on January 29th 1946. Later, reflecting on this time period Habachi states “You cannot imagine how excited I was. I had a site, I had the money, and I had my diggers.” Euphoria did not last long; Habachi was under immense pressure when after four days of digging near the existing shrines nothing had yet been uncovered. His workmen became disillusioned as each passing day brought failure with every turn of the shovel.

Finally, on the tenth day, all hope having been depleted and his workmen openly questioning his decision to excavate, Habachi uncovered three statues. Shortly after this, any questions about the wisdom of his choice to excavate were put to rest. The excavation uncovered a single block sandstone chapel built for Imeni- I’atu, the overseer of a work gang, and it was inscribed with the name of Heqaib. Three other chapels were quickly unearthed including that of the Governor and Superintendent of Priests, Kha-kaure-Seneb as well as an undecorated chapel to the west. It was during this time that Habachi’s talents were for the first time universally recognized, if not officially by the Department of Antiquities then certainly by peers such as the current inspector of Upper Egypt, Henri Riad whom stated “Watching Labib in the field is a rare experience, he is so dedicated so optimistic.”(Kamil, 2007)

Habachi continued to excavate throughout March discovering many more artifacts and inscriptions attributed to Heqaib. Habachi theorized that Heqaib was deified and his suspicions were proven correct when four steles and a duct system for libations were discovered. The duct system started at the front of Heqaib’s shrine to the east and continued to the chapel of Ameny-Seneb to the west. The significance that libations for Heqaib were poured at his shrine, flowing through an offering table and then to a second offering table at a lower level continuing to the western chapel of Ameny-Seneb provided proof that Heqaib was probably worshiped as a god with divine power. His views were also supported by the finding that the name Heqaib became a common Middle Kingdom name. The cult of Heqaib remained popular, not coming to an end until the 13th Dynasty. Having found what he hoped was a springboard to success and acceptance by his peers Labib did not file a preliminary report. He wanted to ensure that when released, the formal account of the findings was complete, accurate and well written. He never anticipated that this decision would lead to the unfortunate chain of events that soon plagued him.

Conclusion

Although Labib Habachi was not born into prosperity, he was able to obtain the education necessary to become an Egyptologist. This was only the beginning of the difficulties he faced in his pursuit of his first job and then, more importantly to Habachi, acceptance from his peers.

Habachi had a stubborn determination to succeed, refusing to back down when he held a controversial opinion. Sometimes this was perceived as his lack of culture and played into the hands of those who opposed him in the Antiquities Department. Effectively stalling his opportunities for advancement Habachi never received the respect or recognition his accomplishments should have afforded him.

In part two, I will look at the impact Habachi’s excavations at Elephantine Island and the continued controversy with the Antiquities Department and foreign colleagues had on his career. I will also explore how marriage to a dignified and respected socialite advanced his opportunities beyond his most optimistic expectations.

Image Credits

Figure 1, Labib Habachi, Kamil, Jill, Labib Habachi The Life and Legacy of an Egyptologist

Figure 2, the village of Salamun, Copyright expired, Public Domain

Figure 3, Courtyard of the Mosque of Al Azhar, University of Cairo (1907), Public Domain

Figure 4, Interior of Hall of Instruction, University of Cairo, Egypt (1901), Public Domain

Figure 5, Selim Hassan, Creative Commons Attribution – Share Alike 3.0., Attributed to Mikerin

Figure 6, Walter Emery, Public Domain

Figure 7, Ruins of Tanis, Public Domain

Figure 8, Pepi I Copper Statue, Public Domain

Figure 9, Aswan, Elephantine, West Bank, Egypt, Creative Commons 2.0 license

Figure 10, Elephantine Island Statue, Creative Commons 2.0 license, Attributed to Karen Green

Figure 11, Sanctuary of Heqaib, Public Domain

Bibliography

Forbes, D., 2011, Giant of Egyptology Labib Habachi, KMT 22 No 1 p. 77–80

Ghali, M., 1991, The Coptic encyclopedia, volume 5, Macmillan

Kamil, J., 2011, Labib Habachi Remembered, KMT 22 No 1 p. 78-79

Kamil, J., 2007, Labib Habachi The Life and Legacy of an Egyptologist, The American University in Cairo Press

Thompson, J., 2007, Egyptians in Egyptology, Al-Ahram Weekly No 876 p. 1-5

Wilkinson, R., 2000, The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson

By

By