By Andrea Byrnes. Published on Egyptological, In Brief, on June 30th 2011.

Shown in England on BBC1, Monday 30th May 2011, 2030-2200.

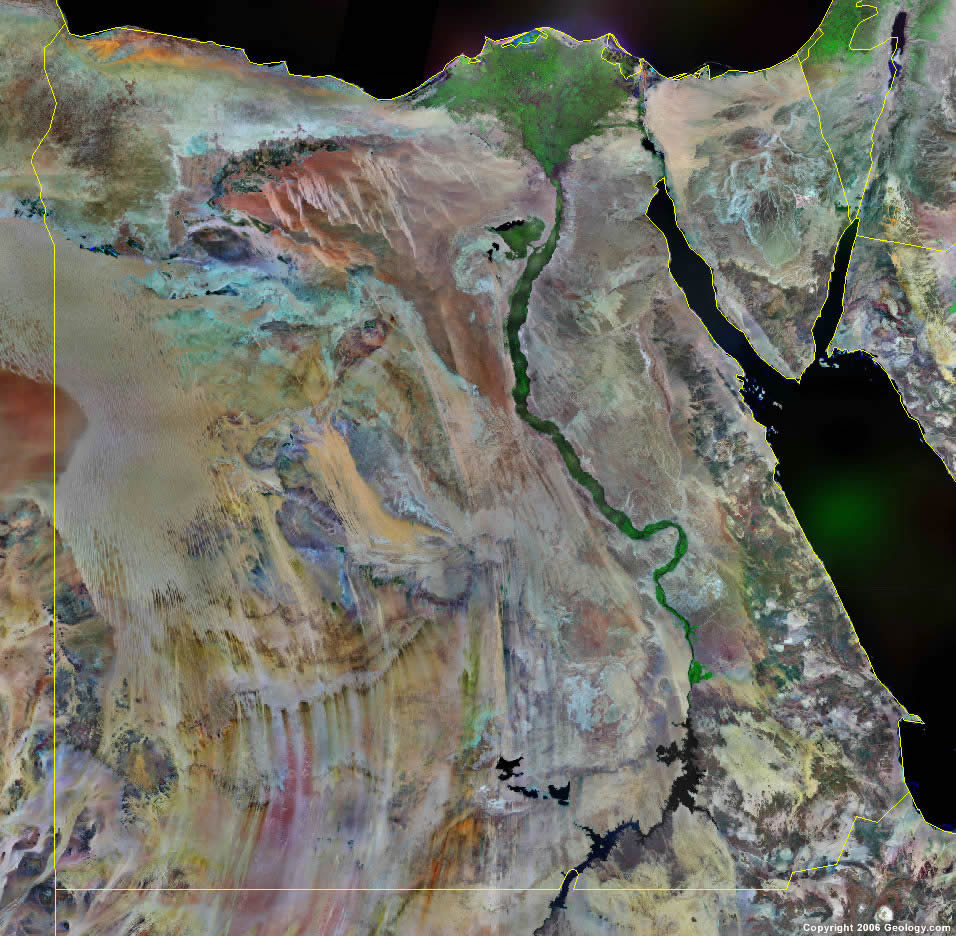

“Space Archaeology” is the new buzzword adopted by the BBC in its documentary “Egypt’s Lost Cities.” Not to be confused with the branch of archaeology studying orbiting space debris, it describes instead the use of satellite images to locate archaeological remains beneath the earth’s surface.

Dr Sarah Parcak has been using satellite images with infrared overlays for the last decade to locate sites which have not been previously recorded, identifying sites in staggering numbers and expanding knowledge about the extent and type of building activity throughout Egypt, challenging previous estimates of Pharaonic population numbers. Parcak’s aim is to map the entire of sub-surface Egypt from space, searching for settlements, temples, palaces and pyramids – the entire human landscape of Egypt in the past. Her work focuses mainly on Pharaonic structures but she has also helped to identify prehistoric sites.

The show, lasting an hour and a half, communicated Parcak’s work quite well, in spite of the two very distracting presenters Dallas Campbell and Liz Bonnin. Their combination of ignorance and wide-eyed astonishment made them a somewhat baffling choice for the job. The show jumped around between case studies of Parcak’s work and rather random visits to sites like the Great Pyramid and the Valley of the Kings, apparently thrown in for a bit of three-dimensional glamour. Similarly, there were interviews with well known Egyptologists like John Romer and Salima Ikram which, whilst interesting, were not always particularly relevant to the topic. A rather more focused approach would have reduced the show by half an hour, and would have made it more convincing as a documentary.

The satellite research does not require gimmicks to make it digestible. Parcak herself came over very well, explaining her research clearly and professionally whilst still conveying the excitement that she clearly feels about locating new and important sites. The parts of the show that stuck closely to Parcak’s work were the best, the case studies containing a real “wow” factor of their own.

The first site looked at in depth was the vast royal and elite necropolis of Saqqara, to the south of Cairo. Using satellite photographs Parcak had identified what looked like the foundations of a possible pyramid. On the basis of the size and location it was tentatively dated to the Middle Kingdom, and Parcak expressed her frustration about being unable to prove many of her theories because of the difficulties of obtaining permission to excavate. At Saqqara her request was rejected but Hawass eventually started to excavate there with his own team. They found what may be an enclosure wall for a pyramid complex but the Egyptian revolution interrupted investigations and it is impossible to say whose pyramid it might belong to at this stage.

At Tanis (inevitably “featured in Raiders of the Lost Ark”) a test trench was dug by the French mission working there to test Parcak’s findings. The discovery of a building just where she predicted already satisfied everyone concerned and, as Parcak said, “it’s something that validates the satellite work.” The centre of the Twenty First Dynasty, tombs in Tanis have produced riches equalled only by those in the Valley of the Kings, but is still quite poorly understood. Parcak’s work will certainly contribute to decisions about future survey and excavation. The satellite photographs of Tanis are staggering, showing a massive town extending in all directions, with a vast network of buildings and roads.

At Abydos Parcak was hoping that satellite imagery will find a missing tomb of one of Egypt’s earliest kings. Gunter Dreyer, heading the excavation of the tomb of King Djer, agreed to excavate a trench to locate what Parcak believes might be a collapsed tomb under up to 5m of sand, although she admitted that it was a one in 1000 shot. In the event nothing was located but clean sand.

At Abusir, not far from Saqqara, a number of 5th Dynasty pyramids were built with accompanying sun temples in the vicinity. To date only two of those sun temples have been discovered, but Parcak may have identified a third – a perfect square which seems to be a match for the standard layout of a sun temple. The show re-created its possible appearance in computer graphics, demonstrating why the structure is such a convincing candidate for a sun temple. There are no plans to excavate at this point, but the discovery is potentially very exciting.

The next site to be examined was the eternally fascinating jumble of bumps and dips outside Amenemhat III’s mudbrick pyramid at Hawara, to the southwest of Cairo. Herodotus reported that the building that once stood here, Amenemhat’s mortuary temple, was a “labyrinth” and to him it surpassed the glories of the pyramids. The satellite photographs belie the uninformative undulating earth beyond the pyramid. They show in amazing details the layout of the enclosure wall of a vast mortuary enclosure surrounded by a “rabbit warren” of houses and city streets. The mortuary enclosure was quite clearly a pinnacle of Middle Kingdom architecture.

Still in the Faiyum area the show shifted its attention to a palace complex where the royal wives and children of the 18th Dynasty had lived, one of whom was probably Tutankhamun. Although pock-marked by military bunkers the satellite images reveal original walls and features as well as an entire workers village and waterfront villas for its administration. Peter Lacovara, an expert on palace architecture, estimates that it will take decades to excavate the site.

Back at Saqqara attention shifted to the damage inflicted during the Egyptian revolution. Excavations at Parcak’s lost pyramid were abandoned when the protests erupted in January 2011. Returning to the site afterwards the cameras revealed some grim sights. Hundreds of newly constructed tombs have been erected on archaeological land, all built since Parcak’s last photographs had been taken. At neighbouring Abusir Parcak’s 2009 photographs showed an untouched area of potentially immense archaeological value whilst a post-revolution image showed “hundreds and hundreds of holes,” together with a bulldozer. Egyptologist Salima Ikram mentioned that when the revolution broke out the police mysteriously vanished en masse, leaving these sites vulnerable to damage and looting.

Putting to one side the inappropriate presenters and the unnecessary addition of glamorous sites and famous people, this was an excellently informative programme. At the end of the show Hawass was filmed commending the value of satellite imagery. Parcak’s work has revealed 1250 possible new sites in Lower Egypt alone, of which some 500 are in the Faiyum. Assuming that politics doesn’t stand in their way archaeologists will be at work for decades to come investigating the findings of Parcak and her team, and dramatically expanding our knowledge of Egypt’s past.

By

By