Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 4, February 27th 2012.

By Garry Beuk

PART 1 – The Early Years

Introduction

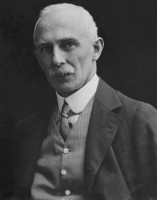

In this article, I will explore the contributions that Arthur Weigall (figure 1) made to the field of Egyptology. I knew of Weigall’s involvement as a reporter during the excavation of Tutankhamen’s tomb by Howard Carter, and his open criticism of Carter and Carnarvon’s exclusive reporting agreement with the Times, but later discovered that he had already had an impressive career in Egypt. That in fact by the time he came to cover Carter’s discovery his career in Egyptology was already over and he had not returned to Egypt in over nine years. What exactly did Weigall accomplish? What brought about the premature end of the apparently promising career of a young man who, despite his rapid advancement, seemed to fade so completely from the world of Egyptian archaeology.

Early Life

On November 30th 1880, Arthur Edward Pierce Weigall was born in England. His early life was marked by the tragic death of his father, Captain Arthur Archibald Denne Weigall, who died in active duty in the same year that Arthur was born. Weigall’s life was molded by the father he never knew. War relics lined the walls of his childhood home and Weigall himself expresses this influence clearly when he looks back and remarks, “Throughout my childhood he was a legendary figure to me: a man of heroic mold, whose quiet eyes looked down at me from the wall” (Hankey, 2007).

His mother Alice (Cowan), known as Mimi, and his older sister Geanie raised him with little support. Mimi was a revivalist Christian missionary, and dedicated the early years of her son’s life working to change the lives of destitute prostitutes in south London as. Weigall witnessed some of the most extreme and unhealthy living conditions prevailing in London at the time, conditions that nearly resulted in the death of his sister, who contracted diphtheria. In 1887 Mimi moved her children to a rural home in Chorlton (south Manchester), and accepted the position of the Lady Superintendent of the City Mission Work in Salford. Many of these experiences had a lasting effect on young Arthur. He would never share his mother’s compassion for the women she served but later in life he wrote a novel, Burning Sands (figure 2), based on his childhood experiences that perhaps served a therapeutic role, incorporating biographical elements.

School – The Beginning

In 1892, at the age of 11, Arthur left his female-dominated household and was enrolled in Hillside School in Malvern (Worcestershire) The all-male boarding school was his first taste of independence and he had some difficulty adjusting to life without his mother, he found it difficult to conform to the standards expected of young men at the elite school. His unhappiness expressed itself in fits of bad behavior that resulted in his being “sent to Coventry,” a form of punishment that meant that he was excluded from all communication from the school faculty and the student body. Weigall suffered spiraling depression and his behavior grew more erratic at one point leading him, , to smash a window, cutting his wrist as he did so.

In 1895 his mother, Arthur and Geanie moved to Buxton in northwest England, where Weigall’s paternal grandfather had been a vicar. Arthur was enrolled in Wellington College, a school deep in tradition, established for the sons of army officers, and where generations of the Weigall family had attended classes. English boarding schools were divided into “houses,” and students were usually placed in the same house as previous family members who attended the school. He was placed in Kempthorne’s House, where other Weigalls had been before him, and found himself once again surrounded by boys from exclusive families, leading him to experience feelings of inadequacy similar to those he had experienced at Hillside.

His fits of rage escalated to physical manifestations with fists and feet flying, which no doubt caused his classmates to distance themselves even more from this ill-suited individual. School officials either did not recognise, or if they did, did not encourage his artistic talent, and passed the years relatively unnoticed. His chances of a career in the Army were sinking away, and he would later reflect on this and say “(there) seemed little likelihood of my having the brains to pass the exams” (Hankey, 2007).

At this time drastic changes occurred in his home life. His mother married his former tutor Reverend George Craggs, who soon moved the family to Everton (Liverpool). Geanie was sent off to finishing school in Switzerland, whilst Weigall himself went to stay with his uncle.

Egypt Calls

Unsuited for the discipline of formal education, Weigall left Wellington at the age of seventeen and visited his father’s brother, Mitford, the vicar of Frodingham. Inspired to research his family’s lineage, through the Weigall line, he discovered his grandmother’s Irish heritage, and read about an Irish tradition that claims a connection between the Irish and Pharaonic Egyptians. Almost immediately this far off exotic land took a hold on Weigall. In his own words he describes this revelation; “Thus I turned to books on Ancient Egypt, and therewith I became so deeply interested in this romantic land that I forgot all about pedigrees and family records, and devoted all my spare time to studying the history of the Pharaohs” (Hankey, 2007).

Weigall spent every free moment he had digesting books on the subject of Egypt. His mother, concerned for her son’s welfare, worked to secure him a future as an accountant. Surprisingly, as he had given it little effort, Weigall passed the required exam and was hired by a leading firm in London. Although employed, he continued to seek out his true calling. Eventually a chance meeting with Denison Ross, Professor of Oriental Languages at University College London changed his life’s direction. Ross encouraged him to develop his interest in Egypt and use his talent for drawing to forge a new path, that of an Egyptologist.

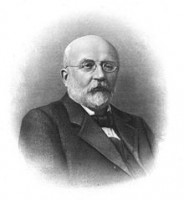

Ross introduced Weigall to the eminent Egyptologist Percy Newberry (figure 3). Newberry encouraged him to remain on the safe path of accountancy, but recognising the benefits of his artistic talent hired him for his first job in archaeology, to do tracings for the British Museum. Destiny would call and young Arthur Weigall would never look back at the drab prospects of life as an accountant, the lure of Ancient Egypt was impossible for him to ignore.

In 1900, under pressure from Mimi to continue his education, albeit in a profession she did not believe was suitable for a man of his pedigree, she enrolled him in Oxford University. In her book “A Passion for Egypt” Julie Hankey offers an excellent summary of the situation as follows: “the ludicrous situation arose in which Weigall was officially being crammed for Greek and Latin, while unofficially he was trying to teach himself oriental languages” (2007, p.23). Perhaps based partly on his previous experiences with formal education Arthur’s heart was not in the task of preparing for University life and he failed “the Smalls” (entrance examinations), which were a requirement for entry into the University as a whole. However in the same year he did, , publish his first academic article on Egyptology, which appeared in the Journal for the Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology.

Mimi was determined that her son was going to receive a proper education but at that time Oxford did not offer instruction in Egyptology. This resulted in the family once again relocating, this time to Leipzig where Arthur enrolled in a German University. He planned to study under Georg Steindorff, the Professor of Egyptology, but first had to learn to read and write German. Berlin not only offered the distractions of big city social life, but also a fantastic museum that he visited for hours on end. Weigall’s past academic short comings would prove no different at Leipzig, when it came to formal study his lack of self discipline had an enormous impact on his learning and as a result, he never became proficient in German and his work with Steindorff was limited to the basic deciphering of hieroglyphs.

1901-1904 – Petrie

Weigall was forced to abandon his studies when an outbreak of smallpox caused Mimi to uproot the family and return to England. Weigall soon forgot all about Leipzig and a degree when he was introduced to the famous specialist in ancient Egypt, Matthew William Flinders Petrie, and was offered a job as the great man’s assistant (figure 4). This he quickly accepted, and his dreams finally appeared to be within his reach. Weigall’s first jobwith Petrie was to catalogue the archaeologist’s hieroglyphic inscriptions. This took place in Petrie’s office at University College London where Petrie was the Professor of Egyptology. Petrie had already obtained the status as the father of modern archaeology and Weigall must have been awed to work so closely with someone he held in such high esteem.

As Petrie’s trust in Weigall grew, Weigall’s duties increased. He was soon given the task of weighing ancient weights, the results of which Petrie published in “The Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology”. If Weigall lacked discipline in formal education, he clearly made up for it when given real life challenges. Petrie was so impressed with his skill and dedication that he offered him an unpaid Assistant’s position in the field. Weigall was finally headed to Egypt where he joined up with John Garstang and Arthur Mace who were also working as assistants for Petrie. He then travelled to Abydos with Petrie and his wife Hilda. Their introduction to Petrie’s archaeological style and somewhat eccentric lifestyle would begin in the First Dynasty Royal cemetery. When this work was completed Petrie moved his students to a newly discovered Twelfth Dynasty cemetery about a mile south.

Weigall was given a shovel and the command of 50 men with whom he was to work side by side. This must have been quite an experience for a 21 year old man, and the work itself uncovered a huge granite sarcophagus within a maze of passages in the limestone cliffs. Any other artifacts that may have at one time been present had long ago been removed by robbers.

Adventure is what Weigall was seeking and perhaps he got this in abundance. In his documentation he describeshow he was clearing these passages when the entrance to a subterranean royal tomb was uncovered. From the dark a voice called out “Go away, mister. We have all got guns.” (Weigall, 1913). Then a gun was fired at him: this was Weigall’s introduction to the oldest profession in Egypt, the tomb robber. Weigall was understandably shaken by the incident, but the thieves were arrested the next day and Petrie sent Weigall a note imploring him to keep moving on the clearance of the tomb.

It is a well known fact that Petrie and his wife Hilda ran a tightly controlled excavation and extravagance was not an option. Petrie and his wife worked the assistants at a fever pace for hours on end, and then provided a minimal amount of food. In his own words Weigall describes the reality of camp life, “One lives in a bare little hut constructed of mud, and roofed with corn stalks or corrugated iron; and if by chance there happened to be a rain storm…one may watch the frail building gently subside in a liquid stream on to one’s bed and books.” (Weigall, 1913) Weigall would gain invaluable experience from his association with Petrie but by the end of the season of 1902 he had had all he could take and expressed to his former mentor Percy Newberry that “I can’t go on with Petrie, I have got so weak and horrid from this beastly food.”(Hankey, 2007).

Following this he went to work with the German archaeologist Friedrich Wilhelm von Bissing in a paid position where he could utilise his artistic talents by copying tombs at Saqqara. In 1902 he worked in the mastaba of Kagemni and then in the mastaba of Mereruka in 1904. Weigall loved the freedom his work provided him. He had ample time to explore his surroundings and gain a real appreciation for the beauty of Saqqara, the desert and its surroundings. The experience awoke his desire to plan future literary projects and even introduced him to the mummy pits, which inspired in him a terror of mummies collapsing down around him as he crawled through the narrow passages.

1904-1905

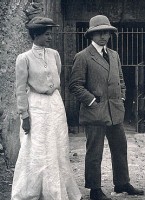

It was in the summer of 1904 that Weigall met and fell in love with an American lady, Hortense Schleiter who was travelling through Europe with her mother (figure 11). After a whirlwind romance they became engaged seven weeks later.

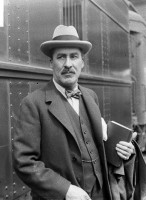

In 1905 Weigall’s dreams came true when he was appointed as Chief Inspector of the southern region of Egypt, based in Luxor, a post hat became available when James Quibell who held the position of Chief Inspector, was moved to Saqqara. Howard Carter (figure 5) backed his appointment and this support may have arisen because of Weigall’s background which was considered to be that of an “uneducated gentlemen”, and would make him less of a rival. Carter believed the position would be subordinate to his own, an assumption that proved to be incorrect.

Weigall realised that his days of excavation would have to come to an end, not due to the protocol of the position, but rather to his own belief that he “always felt that the work of an inspector was to inspect and safeguard and not to excavate” (Hankey, 2007). Weigall’s new position and the salary that came with it, made Hortense’s father see his daughter’s romance in a new light, leading him to allow the two to wed, which they did on October 11th 1905.

In January, 1905 Howard Carter, now stationed at Tanis, sought a trade of posts with Weigall. The offer was quickly refused by Weigall, and the Director General Gaston Maspero (figure 6), was left to smooth things over with Carter. A few months later Carter resigned from his position, a fall out caused by his refusal to play politics and apologize to the French for perceived wrong doings. Weigall, who had previously held high regard for Carter’s work was disillusioned when he discovered that after 12 years in the field, Carter had only visited 20 of the 250 sites in his district and only knew of 100. Weigall was of the opinion was that Carter was a far better excavator than inspector (Hankey, 2007), a job his heart certainly could not have been in. Figure 3

Money doesn’t buy Weigall

The Antiquities Department was in urgent need of money for excavations. Regulations regarding excavating were very loose and Gaston Maspero, head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, would grant wealthy individuals concessions to dig throughout Egypt. Armed with money but lacking knowledge of proper technique, damage to artifacts and sites was inevitable.

Weigall took his position seriously and recognized this, insisting that these patrons hire a qualified archaeologist to supervise their excavations. The first of these patrons was the powerful Theodore Davis whom Weigall describes as, “a very charming American gentleman who in his old age, used to spend his winters on a dahabiya at Luxor, and there became interested in Egyptology.” (Romer, 1981) Shortly after the Weigalls arrival in Luxor, Davis discovered the extraordinary tomb of Yuya and Tuya in the Valley of the Kings. At the suggestion of Maspero, and on the insistence of Weigall, Davis reluctantly hired Edward Ayrton (figure 7) to be his “learned man.” Maspero and Weigall were at odds on this many times. Weigall would refuse a wealthy patron access to Upper Egypt without an archaeologist and Maspero would simply give them a concession in an area of Egypt outside of Weigall’s influence. Maspero could only see the profits that that these concessions provided, whilst Weigall stood by principals that would set future standards to protect the fragile history of Egypt.

From Luxor and Aswan to Nubia to Wadi Halfa Weigall would travel vast areas in this first year, protecting the 250 sites that had previously been neglected. He would swiftly hand out punishment to locals, confiscating stolen antiquities hidden in Bedouin tents. Weigall was not intimidated by government agencies, something that he demonstrated when he prevented irrigation officials from beginning work to dig a canal that he considered a threat to the Tombs of the Nobles at the Gurneh necropolis. Despite the differences between the two men, in his annual report Maspero recognized Weigall’s accomplishments and his success in protecting and setting up systems of policing the sites to protect them until future archaeologists could properly preserve and document them. This brief harmony between Maspero and Weigall would not last much past this first season.

1905-1907

Weigall and his wife travelled south past Aswan through territory now covered by lake Nasser and into Nubia, where they were introduced to a culture where the inhabitants carried weapons, but were as Weigall described, “peaceable and cheerful” (Hankey, 2007). The initial building of the Aswan dam was completed in 1902 (figure 8), but plans were in place to raise the dam which would increase damage to temples, forts and cemeteries that had already seen unprecedented damage. Weigall’s job was to complete a report on how to minimize the damage to these historically important landmarks. A Report on the Antiquities of Lower Nubia, that should have been done years previously by Carter, was completed in record time. The rushed report was nonetheless the most comprehensive done to date. It included drawings, detailed descriptions of temples and their inscriptions, grave sites and other ruins throughout Nubia. It also contained over 200 photographs of the sites and a detailed history of the Nubian people.

Weigall also saved many inscriptions in Aswan that would otherwise have been destroyed when the Department of Public Works was quarrying for rock to build the dam. He hand painted numbers next to over 1000 inscriptions preventing them from being blasted from history. Weigall believed that many of the customs and habits of modern Egyptians mirrored those of their ancient descendants, and that the study of the modern people would answer questions about their ancient counterparts. In his publication Weigall states “Perhaps the most serious objection that can be made to the presence of the reservoir in Lower Nubia is that the rising of the water has led to the routing out of the inhabitants from the ancient mode of life before that life has been studied. These people have stagnated for so long that they have retained their old customs for a greater period of time than have any other of the races of Egypt” (Weigall,1907). This indicates that he was less concerned with the fact that villages were lost, but rather that they were lost before they could be documented. Whatever his motivations, the attention Weigall focused on Nubia would bring about great changes, and as early as 1908, excavations run by Randall MacIver and Leonard Wooley were taking place in a large cemetery in Upper Nubia. In addition, the French, English and Germans were copying temples in danger of being flooded and Signor Barsanti was repairing and strengthening temple foundations.

Weigall confronted the Department of Public Works (DPW) again in 1907 when they started to blast in the now nonexistent quarries of Akhenaten. Started by the king for his building program at Thebes, these quarries in Gebel el-Silsila were remarkable in showcasing the skills the ancients had in cutting stone. The DPW had requested permission to blast, which Weigall quickly denied. The DPW started work anyway, but were forced to stop when Maspero reluctantly stepped in after Weigall threatened to resign. With Theodore Davis’s discovery of KV55 and the controversy surrounding the identity of the mummy found in the tomb, the year was a busy one for Weigall (figure 9). The mummy was first reported to be Queen Tiy, but when examined by Grafton Elliot Smith, Professor of Anatomy for the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , it was found to be a male. This gender change caused the mummy to be re identified as Akhenaten which is a debate that continues to the present day.

The discovery drew upon Weigall’s ability to record history in colorful dramatics when he published a biography on Akhenaten in 1908. Although well received by the public and critics, it did not do much to impress scholars. His mix of facts and theory somewhat blurred the lines between serious archaeological study and work for public consumption, and he created a work that although enthralling, leaned too much in the direction of speculation.

The Tombs of the Nobles

The Theban Tombs of the Nobles (figure 10) are located in the low hills of Shekh abd’el Gurneh and further north in El Assasif between Hatshepsut’s temple and the Ramasseum. They are rock chambers carved for the nobles of the Eighteenth Dynasty. What was unique to these tombs, and a complication for excavation and preservation, was the fact that many were accessible only through modern homes built on top of them.

After returning from Nubia in November of 1905, the preservation and documentation of these mortuary chapels became Weigall’s obsession for the next six years. The work was difficult as the worst predator of all, people, had been destroying the painted scenes for centuries. Wet squeezes, outlining of the scenes in heavy lead pencil for copying, smoke damage from torches and campfires, and worst of all, sections hacked out for sale to museums and private collectors, had done immeasurable damage throughout the ages.

Documentation through sketching and painting had been completed by many in the past, but nothing had been done to preserve the temples and stop the deterioration of the priceless paintings. Weigall was determined to correct this, and had a wall constructed to prevent overnight illegal excavations. Weigall understood that punishment only went so far in changing the behavior of thieving peasants, and instead he chose to attempt to change the conventional thinking of educated Egyptians. He held a meeting with the higher class residents of Luxor and successfully secured funding that was used to repair and safeguard many of the previously threatened tombs.

With the financial backing of British industrial chemist Robert Mond, by the 1909 – 1910 season the protection was completed, and a system for continued study was put in place. Weigall felt that Museums greatly contributed to the problem of stolen antiquities, by inadvertently creating a market to secure the best and most original artifacts for display, each country wanting it’s own museum to have the best collection. His solution was that the original artifacts should remain in Egypt and high quality reproductions used in Museums. His passion on this topic was most evident when he published Archaeology In The Open in 1911, which openly criticized Western Museums for just this sort of behavior. In dramatic fashion Weigall proclaimed the sale of artifacts to create “black murder in his heart.”(Weigall, 1913) He utilized his ability through gentle persuasion, to influence and secure agreement from prominent local dealers not to purchase fragments they knew to be stolen.

Conclusion to Part 1

Weigall found a great deal of success pursuing an unlikely goal, that of an excavator. His modest background and lack of education did not prevent him from obtaining an even more unlikely role, that of an Inspector. He did not fear confronting wealthy patrons or government agencies in an attempt to protect and document monuments spanning from Luxor to Nubia. Weigall travelled extensively these first seasons, involved in numerous excavations, and his attention to the preservation and detailed recording of the Tombs of the Nobles saved them from likely destruction.

In part 2 (Edition 5), I will look at more accomplishments that Weigall made as he became a more seasoned Inspector. I will also investigate how his drive for success, recognition and promotion caused him to make choices that inevitably tarnished the reputation he had worked so hard to achieve.

Bibliography

Hankey, J., 2001, A Passion for Egypt, Taurus Parke Paperbacks

Hawass, Z., 2005, Tutankhamen and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs, National Geographic Society

Reeves, N., 1990, The Complete Tutankhamen, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London

Romer, J., 1981, Valley of the Kings, Castle Books

Weigall, A., 1909, Travel in the Upper Egyptian Deserts, William Blackwood and Sons

Weigall, A., 1910, The Life and Times of Akhnaton, Thornton Butterworth Limited

Weigall, A., 1913, The Treasury of Ancient Egypt, Rand McNally & Company

Image Credits

Figure 1, Arthur Weigall, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years.

Figure 2, Burning Sands, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years.

Figure 3, Percy Newberry, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years.

Figure 4, WMF Petrie, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years.

Figure 5, Howard Carter, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years.

Figure 6, Gaston Maspero, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years.

Figure 7, Edward Ayrton, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years.

Figure 8, Aswan Dam, Public Domain, First published prior to 1923, Copyright expired.

Figure 9, KV55 skull, Public Domain, First published prior to 1923, Copyright expired.

Figure 10, Tombs of the Nobles, GNU Free Documentation License, Credit for photograph attributed to Steve F.E. – Cameron.

Figure 11, Arthur Weigall and his wife Hortense, Copyright expired.

By

By