Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 4, February 27th 2012

By Howard Middleton-Jones

For Howard’s introduction to the topic of Coptic heritage see his previous article in Edition 3

Introduction

Although the religions of ancient Egypt and Coptic Christianity are fundamentally different, there are a number of parallels and similarities between the internal arrangements and layouts of the Pharaonic temples, and those of the later Coptic churches. Both Ancient Egyptian temples and Coptic churches were places of worship, each containing space designed to incorporate symbolic elements and to allow for the performance of specific activities. They were built according to certain formulaic conventions that dictated how that space should be employed by different levels of the clergy and the public. The most common features that temples and churches share are an inner sanctuary with shrines, and an outer courtyard.

The Sanctuary

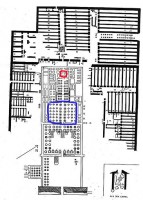

Three shrines are often located in the inner sanctuary of ancient Egyptian temples , each shrine being dedicated to the Holy Triad, a group of three gods, or divine family. This divine family normally consisted of a father, a mother and a child. An example of a Holy Triad or cult gods is the Theban triad Amun, Mut and Khons (Plan A)

This form may parallel the internal arrangement of the Coptic church, such as the three eastern chapels, demonstrating clear similarities with the idea of the Holy Christian family of Joseph, Mary and Jesus Christ as a child, or the concept of the ‘Father, son and Holy spirit.’

An example of this form may be seen at the monastery of Anba Bishoi, Wadi el-Natrun, in the Church of St. Pshoi, its founder, where a triple sanctuary is located. The north sanctuary is dedicated to the Holy Virgin, the middle sanctuary dedicated to its founder, St Pshoi, and the southern sanctuary dedicated to John the Baptist.

In the Pharaonic temple the shrines are arranged around a courtyard, while in the Coptic Church the shrine is located within the ‘haikail’ or central apse. This contains three altars, where the ‘high altar’ contains the Holy relics of a Saint or martyr. These relics are often placed in a coffin-like timber box and covered with silk and brocade (Figure 2).

Churches in Egypt also arose out of the plans of later Christian Byzantine and Roman Churches, such as the Roman Basilica. However, it was not until the 4th century AD that the larger structures appeared in Egypt under the sponsorship of Emperor Constantine. He and his mother, Helen (an avid collector of Christian relics) did much to promote Christianity throughout the Empire and it was she who laid the original chapel foundation which is now the site of the Greek orthodox monastery of St Catherine’s in the Sinai.

The Basilica type construction can be seen in the large open floor plan area and the use of vaults, arches and the materials utilised in their construction. The Church at Hermopolis Magna (ancient Egyptian Khmun) at El-Ashmunein (Coptic ‘Shmounein) in the governate of al-Minya is a good example of this type of construction.

Another site that demonstrates an excellent example of the use of a Basilica style layout is the Coptic Church integrated within the temple of Hathor at Dendera, located in Qena north of Luxor on the West Bank of the Nile (figure 3). The Church comprises a nave with two aisles and a trefoil-shaped sanctuary.

Building material was limited to whatever was available locally, and because of the lack of availability of timber in Egypt, this often led to the re-use of building materials from earlier temples. In many Coptic Churches it is common to observe the occasional integrated stone with hieroglyphic characters. An example of this isthe cartouche of Amenemhat I (12th Dynasty) which was discovered within the walls of the monastery of Dayr el-Baramous in the Wadi el Natrun. Other churches made use of existing Pharaonic temples, sometimes even utilising tombs, using the existing structure that only needed slight modifications to adapt them for Christian use. One of these temple conversions can be found in the mortuary temple of Ramesses III in Medinet Habu. Here one of the temple courtyards was converted into a church to serve the people of the Coptic town of Jeme, which had grown up around the temple. Many columns from that period still survive at the site (figure 4).

At Amarna, a Coptic (possibly monastic) settlement high on the hills that overlook Akhenaten’s town, re-used the New Kingdom rock-cut tomb of Panehsy as a church. The conversion of a rock tomb posed particular challenges, and features incorporated were presumably considered to be of liturgical importance. The tomb divided the main space into two, with the space around the altar mirroring the secluded, inner sacred spaces of ancient temples; niches for water vessels suggest water played a part in Coptic ceremony, reproducing on a small scale the cleansing waters of sacred temple lakes; and a niche cut into the rock and fashioned with a hemi dome which both harks back to Old Kingdom domes, and is a precursor to later built domes as explained later in this article.

Domestic worship

Some Christian religious activity occurred beyond the confines of the church, and these bear little resemblance to either Pharaonic or Coptic arrangements for formal worship. Because of the on-going Roman persecution during the early Christian period in Egypt, , the Coptic Egyptians were forced to gather and worship in the privacy of their own homes. The Greek word for Church, ‘Ecclesia’ originally referred to ‘assembly’, and did not refer to an actual building. Rather, it referred to a location where people gathered for liturgical celebration. Later, some houses were enlarged, adapted and furnished with the trappings for Christian worship. In this way the ‘House Church’ appears to demonstrate the natural progression of a small communal space into a sacred space.

In ancient Egypt, parallels may be found in the Amarna period, where a new religion was introduced and the old gods rejected in favour of a new single deity, the Aten. However, in domestic areas of the town, items have been found that indicate the affiliation of residents with some of the traditional icons of the old religion , namelyamulets and statuettes representing ideas that were closely tied in with the theology that had evolved since the Old Kingdom.

Monastic Architecture

It was in the Coptic Church’s monastic tradition thatworship and the resulting architectural traditions diverged significantly, although one element, the cupola (or dome) survived. In Ancient Egypt the priesthood was centred on vast temple complexes, and the priests themselves were drawn from elite families, whereas in the monastic tradition, although many monks did come from wealthy families, there was no restriction on who could become a monk. In Egypt, one of the most prominent ideas of monastic worship was that of isolation.

Although in later centuries the Pharaonic and Roman temples were re-used as places of Christian worship, the majority of early Christian monastic sites were developed out of rock hermitages and sacred places. This is evident in the number of locations that the Holy Family visited on their flight into Egypt. Many churches and monastic sites were developed in the immediate vicinity of these sacred sites.

The early monastic hermitage sites demonstrated the lone ascetic style that the monks experienced, many of which were distributed throughout the deserts of Egypt. Hermitages were isolated dwellings usually found on the desert margins, and occupied by a single individual. Hermitages could be man-made, or as in some Egyptian examples, could be caves used to achieve high levels of isolation. Two well known sites are located at Wadi el-Natrun in the Nile Delta, north-west of Cairo, and at the more deserted area of Wadi el-Rayan in the Western Desert near Fayum (Figure 5).

In the 2nd to 4th centuries AD the hermitage sites at Wadi el-Natrun developed into small clusters of individual small ‘houses’, or ‘manshobias’ for use by the monks.

The ‘manshobia’ consisted of two rooms and a well, while additional areas for prayer, worship and eating were added later. The materials used were mainly mud brick, twigs and palm branches from the nearby lake area. Bishop Samuel al-Syrians of the monastery of St. Syrians reconstructed one of the larger Manshobias’ in the 1990’s, where several monks would have originally inhabited.

Many smaller ‘cells’ were also constructed for the individual monk, where monasteries developed around these cell clusters and which continued to be used for the occasional ‘ascetic’ experience (figure 7).

A similar type of monastic housing was discovered at Kellia, north east of Wadi el-Natrun, where over 1600 monastic ‘units’ were found. The Kellia site demonstrates the fusion of the ascetic (anchoritic) and that of the cenobitic (communal) lifestyle later developed by the monasteries. At Kellia, monks would live alone, or in groups of two or three, for most part of the week, coming together on Sundays for worship and meals, thus forming a communal group.

The site was founded by St. Amun in the 4th century, an anchoritic figure, but developed the idea of monks living side-by-side. The construction of these ‘houses’ was similar to that of the manshobias at Wadi el-Natrun, but in Kellia they were mainly constructed of unbaked brick. They were also more complex in their layout, design and contents. The area around Kelli and Wadi el-Natrun produced a high quality mud brick, which consisted of a combination of reasonably high surface water and the excellent silt material available produced a longer-lasting, brick of higher quality.

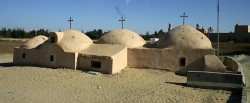

With the increasing size and complexity of the monasteries, and the standardization of some of their features, the cupola or dome was introduced (figure 8). This basic dome structure can be traced to the Old Kingdom, which is evident at the tombs of the 6th Dynasty nobles at Saqqara. The tombs consist of sloping corridors with an arch of bricks leading to the individual tomb and chamber. One of the oldest brick vaults known dates to circa 2680-2180 BC.

The dome in Coptic architecture was constructed of dried mud brick, rubble-stone and also wood when it was available. During the 5th century the dome was built above three apses, thus offering three cupolas, representing the Holy Trinity, while later in the 6th and 7th centuries five cupolas were often built. By the 7th and 8th centuries a large central dome was constructed with the smaller domes covering the sanctuaries.

The Main central dome was often painted with an icon of Jesus Christ accompanied by angels and saints, the premise being that the dome reflected and confirmed the building in an earthly heaven and a heavenly earth.

Throughout the early Christian period in Egypt, the monasteries were subject to constant attacks by desert raiders, Roman persecution and then the Persian invasion in the early part of the 7th century AD,. Many Churches were destroyed during these periods, as a result of which the monks began to secure the monasteries with high walls and the introduction of the ‘qasr’ or keep. The purpose of the ‘qasr’ was to offer a safe area in times of attacks, whereby a small drawbridge would give the monks access and would also be pulled up into a recess in the wall to prevent the raiders from entering the Church (figure 9).

The potential for constructing new Churches in modern times is complex and bound up in political and religious issues, where the Islamic majority have regulations stipulating certain limitations on building Coptic structures. However, in recent times the cathedrals of Aswan and Cairo have been built in keeping with many of the ancient traditions, and on the West Bank in Aswan a completely new large Church has been under construction since 2010.

In light of the recent revolution in Egypt coupled with hopefully positive changes for a brighter future for the people and culture of Egypt, we may witness a renaissance in the way the Coptic heritage is considered and a resurgence of building construction within the Christian community.

Bibliography

Gabra. G 2002 Coptic Monasteries. Egypt’s Monastic Art and Architecture. AUC press Cairo.

Gabra. G, J.M van Loon, G (eds) 2007 The Churches of Egypt. AUC press Cairo

Samuel al Syriany, Bishop, Habib B 1996 The Coptic Dome

Website reference.

Temple of Dendera layout, accessed February 10th 2012

http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/denderatemplecomplex.html

By

By