Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 4, February 27th 2012

By Brian Alm

(Editor’s Note: This is a companion piece to accompany Part 4 of Brian Alm’s series on Ancient Egyptian Religion in this edition of Egyptological, but can be read as a stand-alone article.)

Introduction

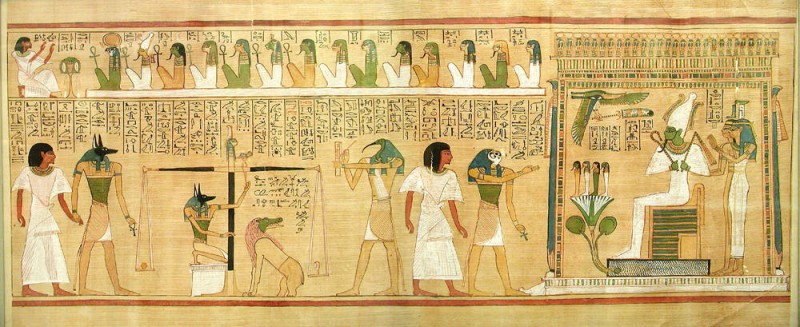

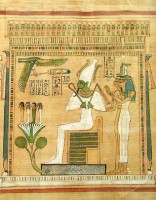

This article looks at the most important scene in a funerary text that the Egyptians called the Book of Going Forth by Day, better known today as the Book of the Dead. It consists of a series of spells to help the deceased tackle the challenges of the Afterlife. The subject of this article is the vignette (illustration) accompanying Spell 125, the scene in the Court of Judgment, where the worthiness of the dead is assessed before he or she is granted entry to the Afterlife.

The Book of the Dead was one of a series of New Kingdom funerary texts, all of which have their roots in texts from earlier periods, which will be mentioned below.

In the Book of the Dead, the key figure in the Court of Judgment — a place known as the Hall of Double Justice, or Hall of Two Truths — is Osiris. His prominence is only fitting, since the objective of all the ritual that has gone before is to give the deceased access to the Afterlife. Osiris sits there on his throne, waiting for the Judgment to be carried out so that he can welcome the deceased into Eternity. He is calm and stationary — the very image of stability. Indeed, a common symbol for Osiris, and a common amulet placed in mummy wrappings, was the Djed pillar, indicating “stability” and known as “the Backbone of Osiris.” The scene at the throne is static and eternal.

The action is at the other end of the picture, where three key deities are performing their duties. The jackal-headed Anubis is weighing the heart of the supplicant as the ugly beast Ammit, known as “The Devourer,” “Bringer of the Second Death” — a hybrid monster, part lion, part hippopotamus, part crocodile — crouches by the scales drooling, waiting to gulp down the failed soul. The ibis-headed Thoth is poised to record the verdict on his slate. Various deities are ranged around the scene, serving as Judges or in other roles important to the ritual or the ideology that had developed over the span of many centuries. Overlooking this scene is the Ba — the winged representation of the personality of the deceased — perched and ready but not yet able to take flight as a risen being.

Even though Osiris is pictured at the far end of the Judgment scene, indicating the conclusion of the proceedings, his presence nonetheless dominates the scene, as a confirmation of the ultimate purpose of all this.

Picturing the final confirmation of the truth, justice and order of things in the same scene as the Judgment, when the success of the soul remains dicey (at least theoretically), seems akin to flipping to the last page of the book to see how the story turns out. The difference is that in the Egyptian case, the deceased wrote the book. Not technically speaking, no — but copies of the Book of the Dead were stockpiled in the shops of scribes, waiting for the blanks to be filled in with the name of the deceased when the time came. The purchaser with foresight, or, in the case of an unexpected death, his or her heirs, could go to a shop and order a customized Book of the Dead with the spells he or she wanted, or could afford, and have the name put in then.

So the outcome was a foregone conclusion, even though the ideology had to be reckoned with — the threat of failure, even though theoretical, was the counterpoise to success: the Egyptian concept of Duality. The dead were called hesyu, “the Blessed Dead,” “the praised ones,” so the living, too, must have had confidence that the departed would prevail over death. In fact, the book came with a guarantee: in Chapter 70 of the Theban Recension of the Book of the Dead, it says: “As for him who knows this book on Earth, he shall come out into the day, he shall walk on Earth among the living, and his name shall not perish forever” (Faulkner 1998, p. 108). So many deities are associated with destiny and the potential for life — Meskhenet, Shai, Heket, the Seven Hathors, and others — it seems that even at birth the die was cast.

Let’s always bear in mind that both present life and eternal life were expressed with the same word, ankh, and that the Egyptians called this the Book of Going Forth by Day, not the Book of the Dead. Even the title of the book presumes that the soul will succeed. It is nonetheless an exciting play.

The Literature of the Underworld

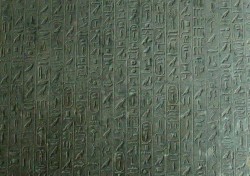

The Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom were exclusively for the king. Osiris first appeared in his role as god of the Afterlife in the Pyramid Texts, but the primary emphasis was a celestial Afterlife, and it was restricted to royalty. These texts were inscribed only on the walls inside pyramids, beginning with Unas in the 5th Dynasty, but it’s clear that their roots go back much earlier, even into predynastic times.

The Coffin Texts, introduced in the Middle Kingdom, developed the ideas of the Pyramid Texts and extended the promise of the Afterlife to the commoners. This was a confirmation of the so-called “democratization of the Afterlife” that had begun perhaps as early as the late Old Kingdom but had taken hold in the First Intermediate Period. Now, with this development, all the dead were to be called “Osiris.” In the Coffin Texts Osiris took up permanent residence in the Underworld (Duat) as lord of the dead. The Coffin Texts were written on coffins, particularly inside the lid, so the deceased could read them easily.

In the New Kingdom the chief document was the Book of the Dead, which had made its first appearance in the Second Intermediate Period and offered, ultimately, a selection of 192 spells to anyone who could afford to buy a papyrus scroll, customized for his or her personal guidance into the next world. These guidebooks to the Afterlife were placed in the coffin or nearby, within easy reach of the deceased.

For the pharaohs, there were other texts, too, that emerged in the New Kingdom: the Book of Amduat (first used by Hatshepsut), the Book of Gates (Horemheb), the Book of Caverns and the Book of the Earth (both Merenptah), the Litany of Ra (Thutmose III), and others, which present variations on a common theme: the sun’s nocturnal journey back to rebirth and the deceased’s participation in that triumph over death (Dodson 2008, p. 129ff).

All three main bodies of underworld literature — the Pyramid Texts, the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead — offered spells to guide the deceased safely through the mysteries and obstacles of the Underworld on the journey to Eternity. For the common people the Book of the Dead — the culmination of the earlier texts — made the journey to the Afterlife not only possible but personal: Eternity was open to all who could pass the Judgment in the Hall of Double Justice and be declared Justified (Vindicated).

The question arises, why would the royalty want to allow such a prize as eternal life be extended to the common rabble? I believe the answer is clear: if people had to justify themselves in order to achieve it, they would have to account for their support of order during their lives, and on their level that meant the social and civil order. It was the duty of Egyptians to uphold order through their devotion to the pharaoh and their behavior toward one another.

Deities of the Underworld

Let’s look at the characters in this drama that is playing out in the vignette of Spell 125. The protagonist, of course, is the deceased, since the whole play is about him. It’s not about belief in a creed or the strength of his orthodox faith — it’s ultimately about order, and what the deceased has done to preserve it. Saying what he did (or did not do) was tantamount to reality, so words would do if actual deeds fell short. But the words had to be exact, because they were the magic in the ritual. When the dead man made these declarations before the 42 judges, or assessors, in the Hall of Double Justice, magic converted his words into statements that became true.

This litany was the “Negative Confession,” in which the deceased had to state all the wrongdoings he had not committed, addressing each Judge correctly by name and denying a particular fault: “O Wide-strider, who came forth from Iunu, I have not done wrong,” “O Swallower of Shades, who came forth from Kernet, I have not slain people,” “O Terrible of Face, who came forth from Rosetjau, I have not destroyed food offerings,” “O Breaker of Bones, who came forth from Herakleopolis, I have not stolen food,” “O He Who Does Not Allow Survivors, who came forth from Busiris, I have not disputed the king,” and so on.

The goddess Maat, shown as a feather in the scale pan, is the deification of the concept of maat: truth, justice and cosmic order. She appeared in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts, along with many others who still remained in the New Kingdom texts, often in altered, updated or syncretized roles. By the New Kingdom she was considered to be the daughter of Ra; as such, she was also the sister of the pharaoh. Think how important it was for the individual Egyptian’s life to support and contribute to order in Egypt: his eternal life depended on it. Now, at the Judgment, his reverence for the pharaoh, ethical behavior and contribution to order must face up to the daughter of god.

Anubis (Anpu) was the god who prescribed the funerary rites and the god who governed embalming — with the help of Upuaut (also spelled Wepwawet), “Opener of the Ways,” who guided the dead to the Afterlife. Anubis dates back to the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom, in which his daughter was given as Kebehut, the goddess of freshness, to demonstrate that without death there is no rebirth. All of Anubis’ titles express this role: he was the Conductor of Souls, Khenty Amentiu, “Foremost of the Westerners”; Nebtadjeser, “Lord of the Sacred Land”; Tepy-djuef, “He Who is Upon His Sacred Mountain”; Imy-wet, “He Who Serves in the Place of Embalming”; and Khenty sekhnetjer, “Foremost of the Per-Wabet” (the embalming tent). In many New Kingdom tombs he is shown tending to the mummified form of the deceased, as a jackal.

Whatever their other duties were, several deities also had some role in the funerary ritual or in the Underworld. Egypt was a culture focused on the continuation of life beyond death, and so we have, for example, the ibis-headed Thoth (Djehuty), the patron deity of knowledge and wisdom, the inventor of hieroglyphic writing and creator deity of Hermopolis (Khemennu), who is also presiding over the Weighing of the Soul and recording the verdict on his slate.

Some other good examples, which may be overlooked in a brief peek at the Judgment scene, are the two goddesses Meskhenet and Renenutet, standing together left of the scales, whose appearance now “marks the end of one cycle of existence and the beginning of another” (Taylor 2010, p. 221). Meskhenet is the goddess of childbirth, and also of destiny; at a child’s birth, she predicted his future and now, at his death, she comes to the Judgment to testify as to whether he was true to his destiny and will now speak “true of voice.” Renenutet (“Snake who Nourishes”), a goddess of fertility and harvest (“Lady of the Fertile Land”), was also a goddess associated with newborns, as well as the goddess who now protects the mummy wrappings — the cocoon enclosing the life waiting to be revitalized. In addition, she is associated with Shai, also a deity of destiny, or fate, who’s shown standing by the heart being weighed. Shai has accompanied the child all his life and now appears at the Judgment to report on how he behaved.

Once the deceased has passed the Judgment, he or she is said to be “justified” or “vindicated.” Horus (Hor), who now leads the Justified by the hand from the scales of Justice to the throne of Osiris, is the syncretization of the original solar Horus (Horus the Elder, Lord of the Sky) and the Osirian Horus, son of Osiris and Isis, whose four sons protect the canopic jars. As a member of the family of solar gods, the falcon form of Horus, known as Ra-Harakhty (Horus of the Horizon), wears the Ra disk over his head. As the Osirian Horus, he wears the double crown (sekhemty) of Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt. The syncretized roles link him both to the origins of cosmic order and to the pharaohs, all of whom were descended from him — the apostolic order of Egypt.

Horus as the first father of pharaohs and the apostolic succession were ideas founded in a myth known as the Great Quarrel, or the Contendings of Horus and Seth. Horus had to face Seth, his evil uncle, who had killed his father Osiris, in a trial before the gods to decide who would rule Egypt: the older, more experienced, shrewder and stronger Seth, or Horus, the direct descendent of Osiris, who held the birthright. Ultimately Horus won and hereditary succession was ordained by the gods and established on Earth as law; thus the succession of pharaohs was to be dynastic, and not subject to challenge by mortals — and for most of Egyptian history, that did indeed work.

It is important to look beyond the ostensible issues of this trial and see it as an ethical dualism: a struggle between good and evil principles, which depends on ethical behavior to preserve the order of the cosmos. On a cosmic scale, it is a contest between order and chaos. In the world of mortals, that is the issue that will be weighed on the Scales of Justice — one man’s little part in the grand and eternal drama of the universe.

Arriving at the throne of Osiris, we see four small figures standing on a lotus, whose scent is pleasing to the gods. These are the Four Sons of Horus, who protect the canopic jars that hold the liver, intestines, lungs and stomach of the deceased. Each son of Horus is paired with a goddess, much like the male-female pairings in the theology of Hermopolis, as aspects of order in binary balance:

– Human-headed Imseti with Isis (Iset), the wife of Osiris, who, incidentally, instituted marriage as a function of social order.

– Falcon-headed Qebesenuef with Serket, “Mistress of the Beautiful House” (the embalming pavillion), a goddess of protection — especially from scorpions (Serket Hetyt, “she who causes the throat to breathe”), and Horus’ former babysitter; she was also the goddess of conjugal union — she protected couples from being disturbed while they were making love (the Egyptians left nothing to chance).

– Baboon-headed Hapi with Nephthys (Nebthet), “Mistress of the Mansion” (her headdress spells her name: neb+t and hut), and, as the “Goddess of the Desert’s Edge” (i.e., the delicate balance of barrenness and fertility — again, Duality), she is the goddess of the moment when the annual flood comes.

– Jackal-headed Duamutef with Neith, a prehistoric goddess of warfare, given to aggressiveness and belligerence, but also a nurturing and protective mother goddess who invented weaving and blessed the bandages used in mummification.

The emphasis of all this symbolism — the Sons of Horus and their associations with these goddesses — is on the protection of life and order.

Behind the throne of Osiris stand his sisters Nephthys and Isis (who is also his wife) — the Two Kites who mourned Osiris when he was killed, and now mourn all those who have died, with their shrill and mournful kite-like cries along the path to the grave.

At last, there is Osiris himself (Usir/Usira, in Egyptian), who had around 100 names, among them “Mighty One” (user = powerful), He who Triumphs over Putrefaction, Lord of the Living, the Good One, the Good Shepherd, Lord of the Universe, Ruler of Eternity, King of the Gods, et al.

Osiris holds a crook in one hand, for herding and protecting sheep (referring to his role and epithet, “the Good Shepherd”), and a flail in the other, for threshing grain (he had been an early god of fertility who evolved into a god of herding and farming). The flail was Nekhekh and the crook was Heka (heka is also “magic” and “ruler” — an example of the Egyptians’ fondness for multiple meanings and verbal puns). When Osiris evolved as god of the Underworld, these became the symbols of his supreme power — the power of resurrection. In some scenes his throne rests on a plinth, angled on one end, that is actually a hieroglyph for the letter M, i.e., maat.

Osirian religion appears to have taken root in predynastic times, but it really gained traction late in the Old Kingdom, where Osiris first appeared as a god of the Afterlife, in the Pyramid Texts, and through the First Intermediate Period. By the Middle Kingdom Osirian religion was the dominant faith among the people. This was primarily because his cult offered them eternal life and also because he was more like them than the solar gods were: he did not create himself or hatch from a cosmic egg, he had lived as a mortal being, with human joys and sorrows, he was a family man with a wife and son, and he was the victim of horrible injustice, the treachery of his brother Seth. He died, too, just as mortals do — but he rose again, and now offered that good fortune to all Egyptians.

Although Ra and Osiris shared many qualities, they were never syncretized into one deity; they kept their separate identities. Ra remained supreme as the solar god and principle of Creation and Osiris reigned as lord of the world beyond. Osiris did become syncretized with Sokar, a very early god of the Underworld, and also with Ptah, as Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. There is logic in that syncretization: by accruing the power of Ptah, god of craftsmanship, Osiris reinforced his ability to remake the dead as living beings.

While maintaining their separate jurisdictions, it seems that Ra and Osiris did assume complementary roles, something like two halves of one idea of god in Eternity, as the emphasis on both Ra and Osiris in the New Kingdom funerary literature demonstrates. As we will see in Part 5 of this series, tomb architecture in the New Kingdom also reflects that idea.

Conclusion

We have seen, in this admittedly generic view of the Judgment scene, a drama in which all the key themes of Egyptian religion are played out: Maat (order), Duality, and Heka (magic) have all been represented in the triumph of the responsible Egyptian over death.

References

Dodson, Aidan and Ikram, Salima. 2008, The Tomb in Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London

Faulkner, Raymond O., Ogden Goelet. 1998, The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day. Chronicle Books, San Francisco

Taylor, John H. 2010, Journey through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, Harvard U.P., Cambridge, Mass.

Wilkinson, Richard H. 2003, The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, New York

Wilkinson, Toby. 2008, Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, London

By

By