Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 4, February 27th 2012

By Brian Alm

Introduction

Ultimately everybody has to deal with the final fact of life: death. How the Egyptians dealt with it was so profound in its cultural breadth and depth that it gives rise to the biggest misconception about them: that they were fixated on death. It was just the opposite: they were fixated on life. But we have to understand that for them, death was neither final nor fact. The Afterlife was a continuation of the present life, and for both they used the same word, ankh. Figure 1. For them, death was a portal between this world and the next, and the business of the funerary texts was to provide the instructions and magic required to get there, despite the mysteries and challenges of the Underworld. What we call the Book of the Dead the Egyptians themselves called the Book of Going (or Coming) Forth by Day. That puts it in a far different light. But we will follow convention and call it the Book of the Dead.

The Book of the Dead, which first appeared in the 17th century BCE, is the culmination of two prior texts, the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom and the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom. The Pyramid Texts, which were exclusive to the royalty, included about 800 spells and the Coffin Texts, which extended the promise of eternity to commoners, had more than 1,000. In the New Kingdom there were other funerary texts, too, for the royalty, but the Book of the Dead remained the compendium of spells for all Egyptians. By about 600 BCE it had 192 spells, all but 79 of them inherited from the Coffin Texts. People simply picked the spells they wanted in their Book of the Dead, or could afford.

The destiny was always life in Eternity; only the demographics changed. In the pyramid of Unas (5th Dynasty, 2375-2345 BCE, per Ian Shaw’s Oxford chronology), this inscription from the Pyramid Texts assures the king: “You have not gone away dead. You have gone away alive. Go and follow your sun, and be beside God, and leave your house to the son of your begetting. You shall not perish, you shall not end. Your identity will remain among the people even as it comes to be among the gods” (Hawass 2007, p. 40). When the Afterlife was opened to commoners, in the First Intermediate Period, this destiny was the common expectation.

Egyptian friendships ran deep — “ankh ib” was a close friend: one who lives in the heart. Closest of all friends was a spouse, both here and in the hereafter. Figure 2. They even wrote letters to the dead. A well-known example is the letter Dedi wrote to her husband Intef, around 2000 BCE, pleading for him to help their servant girl Imiu, who was ill. “If you don’t help your house will be destroyed,” Dedi wrote. “Don’t you know that it is this serving maid who maintains your house? Fight for her! Watch over her!” (Teeter 2011, p. 157; Time-Life 2004, pp. 137-38) This letter is remarkable not only because it was written to a dead husband, railing at him as if he were still there in person, and not only because it indicates that Intef, now among the gods, was in a position to actually help with earthly problems, but also because it demonstrates the genuine care and concern that Egyptians had for others, especially those of lower station. Later on, we’ll see why that is so significant.

Concepts of the Afterlife

Ra, the sun, was reborn each day, in an endless cycle of death in the West and resurrection in the East. The certainty of the sun’s return each morning and the regeneration of the crops each year made it just as certain that the dead would be resurrected. The land of the dead was called The West (Amentet), the eternal realm of “the Westerners,” and “Lightland.” Figure 3. “The portals of Lightland open for you… Your heart rejoices as you plow… you go outdoors each morning, you return each evening… you waken gladly every day, all afflictions are expelled. You traverse Eternity in joy” (Lichtheim Vol. II 2006, p. 18).

Beyond the grave they expected life would continue, but without pain, affliction or unpleasantness. Murals in the tombs of commoners show them plowing their fields dressed in pure white clothing; obviously there is no dirt in the Afterlife. Their heaven was a garden where they would float on the Lake of Flowers and enjoy the cool breeze. They would go on with their lives — farming, fishing, playing games, even making love. Inscriptions in the tomb of the 18th Dynasty scribe Paheri confirm: “You thrive on water, you breathe air, you drink as your heart desires, your eyes are given you to see, your ears to hear what is spoken, your mouth speaks, your feet walk … your flesh is firm” (Lichtheim Vol. II 2006, p. 17).

“The Egyptians believed in and created a world of supernatural forces so vivid, powerful and inescapable, that controlling one’s destiny within it was a central preoccupation” (Kemp 2007, p. 11). Even their games reflected their preoccupation with destiny. The popular game senet, which was played by the living from the 5th Dynasty on, previewed the journey they would one day take on their own, equipped with the magic of words to unlock the gates and pass through to Eternity. Figure 4. Senet means “passage” — a passage from life through death to life.

Before going on, there are two things we must touch on: the Egyptians’ view of the created world and their understanding of the self as a complex of integrated aspects.

The Three Worlds: Nut, Duat and Ta

The Egyptians believed there were three worlds: the world above, Nut; the world below, Duat; and the world in between, Ta (Earth). The soul of the deceased could travel between these worlds through “false doors” in the tombs and mortuary temples. Figure 5. The false door was “the most potent place in the tomb, as it was the point where the worlds of the dead and the living came together” (Dodson 2008, p. 17). This door was the portal through which the birdlike ba could fly up to visit the living or soar among the stars.

In the Great Pyramid of Khufu the small shafts that rise on an angle through the tomb from chambers deep inside are passages for the soul to ascend to the sky, north to join the “imperishable” circumpolar stars, south to join Ra at the Equator. The soul could also travel to Duat, which was not precisely the “Underworld” but an “Afterworld” or, better yet, “Otherworld,” as Barry Kemp calls it, because the blessed dead existed in a spiritual world that was both above and below at the same time — one of the many peculiarities that frustrate us but did not trouble the Egyptians.

The Aspects of Being

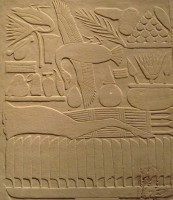

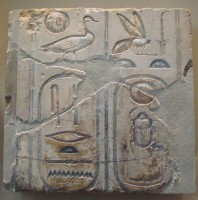

- Figure 6. A complete individual was constituted of integrated aspects of being called kheperu, “manifestations,” as in Horemheb’s throne name (prenomen) Djeserkheperura, “holy are the manifestations of Ra” (reading right to left: Neb-tawy Ra-djeser-kheper-u-setep-en-ra Mery Amun-Ra). Kheperu is the plural of kheper, the scarab beetle.

The Egyptians believed that a person was constituted of several integrated aspects called kheperu, or “modes of existence” (Taylor 2010, p. 17). Kheperu is usually translated as “manifestations,” as in Horemheb’s throne name Djeserkheperura, “holy are the manifestations of Ra.” Figure 6. All of these aspects were interdependent; whatever affected one affected all. Most books focus on five or sometimes only three of them; if you dig into the Book of the Dead you will find there are nine. The others are khaibit or shuyet (the shadow), khu (the brilliant, spiritual casing or aura), sekhem (form, image, power), and khat/khet (the living body/the body after death), which, upon mummification, becomes a sah, a spiritual body.

But for simplicity’s sake, let’s concentrate on these five, the most important: ka (spiritual double, life-force), ba (personality, character, uniqueness), ib (heart), ren (name) — all of which exist in the living person — and the akh (the transfigured being, the glorified form of the deceased), which is the person’s eternal spirit transformed by the union of the ba and the ka at death.

The life-force, the ka, came into being at the person’s birth and accompanied him through life. After death, the ka had to be sustained in the tomb with offerings of food and drink, and the prayers of those left behind. The provisions did not have to be real; models and pictures on the walls would do, thanks to the magic of prayer, ritual and word, and those things written in stone would last forever even if the “Appeals to the Living” — requests inscribed on the tomb for passersby to offer a prayer to sustain the deceased in the Afterlife — went unheeded. Figure 7.

The ka remained in the tomb with the mummy, but the ba — the personality and unique character of the person — could travel to the heavens or visit the living on Earth. Figure 8. So the spiritual life-force and the personality both survive death, but of course a person also has a body, which is a necessary vessel for the spiritual aspects; in fact, so necessary that Old Kingdom tombs often included “spare” bodies: statues (D’Auria 1988, p. 44). A statue also had a ka, and could substitute for the physical body of the deceased if it should somehow come to harm.

At death, ritual and magic could turn the deceased into a new form, a union of the ka and the ba, called an akh — an “eternal and unchanging being made of light” (Dodson 2008, p. 16) who could “dwell among the gods” (Taylor 2010, p. 17). Akhu, the “Shining Beings,” were the Blessed Dead who had joined the gods, and so they were revered, but they also remained personal and present. In her letter, Dedi was addressing Intef as an akh who could intercede and even help out around the house. But how, the skeptics among us may ask, is that possible? There was no mystery or problem for the Egyptian mind in all this. We don’t see the sun at night, but it must be there because it always comes back in the morning; therefore it is logical to believe in the unseen.

And besides, just as in all things Egyptian, there was magic. In Part 1 I discussed heka, magic, as a fundamental of Egyptian religion. Another term for magic was akhu, which was particularly associated with deities who dwelled in the realm of the dead — specifically the magic that a person can perform after death. Magical practices “aim to coerce gods and supernatural beings to perform the will of the deceased” (Goelet 1998, p. 146). Akhu comes from a root word meaning “to become effective” (note also the discussion of akhet in Part 2).

Now let’s return to the ba for a moment, and see why the name (ren) is so crucial. Figure 9. Each day, the ba would ascend to the sky, and each night return to the tomb, eternally — as long as it could find the tomb, which meant that the name on it had to be clear — and provided that the proper prayers and incantations were made, both by the living and by the “living words” inscribed in the tomb. If the name was chiseled off, the ba would not be able to find its home and the dead person would cease to exist. This is the reasoning that underlies the damnatio memoriae, the practice of removing a person’s name, thereby eliminating the possibility of his existence for all eternity. Figure 10.

The heart (ib) was the center of wisdom, morality, character and memory. Thought and will originated in the heart, which was also the repository of conscience and carried the permanent record of a person’s behavior in life. Therefore, the heart had to be prepared to support the person when he was judged in the Hall of Two Truths instead of blurting out some dark secret, and so there was a magical spell to make sure of that, BD Spell 30B: “O my heart of my mother, O my heart of my being! Do not rise up against me as witness, do not oppose me in the tribunal, do not rebel against me before the guardian of the scales! … Do not make my name stink before [the judges]… Do not tell lies about me in the presence of the great god, the lord of the West [Osiris]!”

The crucial thing to note here is the magical power of the word: words could create reality. “Once it was written down, it was inherently magical and could make whatever was written true, especially when spoken aloud, an act which breathed life into words” (Dodson 2008, p. 15). By speaking the words of Spell 30B the deceased gets control of his heart, so it won’t betray him. Words are magic: they create fact.

In summary, the human form after death incorporates the ka, the ba and the ren (name), all of which the person possessed in life, but now the person also assumes a new form, an akh, that can both visit the living and associate with the gods.

Preparation for Entering Eternity

Death could be managed philosophically; decay could not. The physical body had to be dealt with. The Egyptians believed it was necessary to go into the Afterlife with the body intact and preserved — they abhorred the prospect of putrefaction. So they prepared the corpse by draining the bodily fluids, removing four organs (the liver, lungs, stomach and intestines), which would accompany the body after mummification, and discarding the brain, which they thought was useless because its only apparent purpose was to produce mucus. The heart was left in, because it was the seat of the self.

The procedure started in the Ibu, the Place of Purification, where the body was washed and ritually purified. Then it was taken to the Uabet (also called Per-nefer, “the House of Beauty”), the embalming tent where the organs were taken out and put in canopic jars. (After the 21st Dynasty, the organs were put back in the body, and canopic jars could be simply symbolic replicas.) Figure 11. These canopic jars have a symbol-rich lore of their own: each one is a son of Horus, oriented toward a certain cardinal direction, with its own tutelary goddess to protect a particular organ, and, in the New Kingdom, a distinctive head for a lid:

From the discussion of duality, numbers and heka in Parts 1 and 2, it will be immediately clear that the Four Sons of Horus are an expression of order and magic.

Under the supervision of the chief embalmer, Hery-seshta, “he who controls the mysteries,” and the other funerary priests (Hemu-Ka, “Ka servants”), the body was mummified by first drying it out with natron (a crystalline form of sodium carbonate and bicarbonate) for 40 days, then stuffing linen rags, straw or sawdust in the body cavities and the face in order to restore the human shape, then wrapping it in 500 square yards of linen bandages, which alone took 15 days. The whole process took 70 days (7, the magic number), during which the proper spells and incantations were recited by the Hery-heb (lector priest) to enlist magic in the transformation of the corpse into a mummy, the “eternal image” of the deceased, which was now a perfect form called a sah. Figure 12. The wrappings were “a kind of cocoon from which new life could emerge” (Taylor 2010, p. 20). Of course, the mummy could not physically rise from the tomb, but the inventive Egyptians solved that problem with the ba and the akh. Precious, protective amulets (Figure 13) were placed throughout the wrappings to ward off evil; this did not produce the intended effect, however, since amulets were among the treasures that attracted tomb robbers.

There were three levels of mummification, depending on quality and price, but even so, certainly no more than 10 percent of the population could afford it; a rough estimate: six months’ wages. Tombs had to be prepared and stocked with provisions and costly grave goods. This might seem excessive to us, but unlike us, the Egyptians believed you really could take it with you.

Let’s say you are a 42-year-old, 19th Dynasty scribe named Ptahhotep, who has died. Your friends say you “went west,” you are now a “Westerner,” and from now on they will call you “Osiris Ptahhotep.” They were sorry to see you go, and they no doubt felt a sense of distance between themselves and you, a gulf that you have crossed but they have not — much as we may do today, contemplating the body of a person we’ve known. But the Egyptians had an answer for that strange mystery: the ka has left but only temporarily, just wait 70 days and it will be back to reanimate our friend who now lives in the tomb, the “House of the Ka.” Your tomb has everything you will need in the Afterlife, including — most importantly — a copy of the Book of Going Forth by Day to guide you on your way. Now, what lies ahead for you?

Your mummy is taken across the Nile on a boat; fore and aft sit two mourners, your wife and another woman, assuming the roles of Isis and Nephthys, the “Two Kites,” after the bird of prey with a mournful cry. Ashore, you are carried on a sledge, accompanied by your family, friends, priests, servants and professional female mourners who throw dust on their heads and trill like kite birds. (You can hear that very sound today when Arab women trill their tongues to express emotion.) Mourners walk behind the sledge, pulled by men and oxen, ahead of a second sledge carrying the canopic chest or shrine. Servants grease the way with offerings of milk. Then the priests, followed by the embalmers, servants, male muu dancers and musicians, and finally the ox or calf that will be sacrificed: its foreleg will be used in the graveside ritual, after which the animal will be the main course of the funeral banquet. Funeral processions have been common since the 6th Dynasty, so the procedure is well established and it must be performed exactly.

Upon reaching the tomb, your mummy is placed upright and your son, dressed in the leopard skin of a sem priest, touches your mouth with a meskketyu wand, like an adze in the shape of the glyph setep (“chosen”), and a pesesh-kef knife, “a model of the one used to cut the umbilical cord of the baby and necessary for the soul’s rebirth” (Dodson 2008, p. 20) — everything about this whole process is concerned with the renewal and continuation of life. The sem priest says, “I touch your mouth, that you may speak.” This is the Opening of the Mouth ceremony. Figure 14. Now you will be able to use words to put the power of magic at your command as you proceed through the gates of the Underworld and then defend yourself in the Court of Judgment.

This ritual has been conducted since at least the 4th Dynasty, and no doubt much earlier — the pesesh-kef knife goes all the way back to the Predynastic Period (Wilkinson 2008, p. 177). Now in the New Kingdom the ceremony involves 75 separate acts. The sem priest touches your eyes, ears, knees, restoring life to your senses and limbs. You are committed to the grave, the tomb is sealed, and those you’ve left behind begin partying — they’ve brought along enough food and drink for a lavish feast. At the end of the event, everything involved — the leftovers, dishes, pots, flowers, embalming tools and materials, everything — will be buried as well. Figure 15. Your family and friends will return to your tomb each year, during the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, to celebrate your life among the Blessed Dead.

Meanwhile, you find yourself traveling through seven gates in the Underworld. At each gate you are stopped and challenged to say three names: those of the gatekeeper, guard and announcer; at the first gate, for example, “He whose face is inverted,” “Eavesdropper” and “The loud-voiced.” You are equipped to do this: you have a voice that has been restored in order to speak the words of power, and you have the necessary knowledge, from Spell 144 of your Book of Going Forth by Day.

Judgment in the Hall of Double Justice

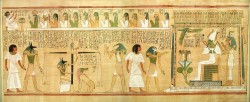

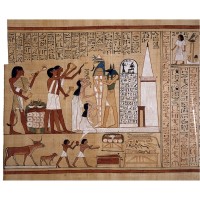

At last you find yourself in the Court of Osiris, presenting yourself for Judgment in the Hall of Double Justice (or the Hall of Two Truths). Figure 16. As the names imply, there will be two parts to the process. First you must address the 42 assessors (or judges) by name, one at a time, each time denying a specific sin. “I have not done crimes against people, I have not mistreated cattle, I have not blasphemed a god, I have not robbed the poor, I have not caused pain, I have not cheated, I have not stolen, I have not committed falsehood, I have not acted in lust, I have not slandered,” and so on. This is the Negative Confession, where you account for how you’ve treated other people, especially those not as well off as yourself. You must testify to your ethical behavior.

Now, to be sure you are not lying, Anubis weighs your heart on the scales against a feather of truth, which is Ra’s daughter Maat. If your heart is not weighed down by wrongdoing, Anubis will report to Thoth, “He speaks true of voice” (ma’a kheru — that is, you are aligned with maat: truth, justice, order; the order of the cosmos), “he is Justified.” This comes as a relief, because the beast Ammit waits, drooling, to devour your heart and eliminate you from existence forever if you are proven false — known as “the Second Death.”

- Figure 16. Judgment in the Hall of Double Justice: the deceased addresses the Negative Confession to the 42 judges and Anubis weighs the heart against a feather, Maat, to verify the truth of the confession while Ammit, the Devourer, crouches and drools, waiting to eat the soul of anyone found unworthy. Thoth records the positive verdict and Horus leads the Justified to the throne of Osiris, who welcomes him into Eternity. Before Osiris are the Four Sons of Horus; behind, Isis and Nephthys. Photograph copyright Trustees of the British Museum.

Now Thoth asks, “Why have you come?” “I have come here to report.” “What is your condition?” asks Thoth. “I am pure from evil,” you say. “To whom shall I announce you?” “To him whose roof is fire, whose walls are living uraei [cobras], the floor is water.” “Who is he?” “He is Osiris.” (You are careful to follow the precise order and form of the litany, and again to report the names and recite exactly as called for — the words themselves are your magic keys.) Thoth announces the verdict: “I am making just the name of the royal scribe Ptahhotep, who is united with Osiris. His heart came forth on the scales of justice and evil was not found. Proceed,” Thoth tells you, “you are announced.” Thoth writes down the verdict and Horus leads you by the hand to the throne of Osiris, who welcomes you into Eternity.

Now, could anyone really be that innocent? No. “The Book of the Dead takes for granted that the [deceased] will have done some bad things… The Egyptian view allowed for two contrary streams of thought, one which denied that any wrongdoing had been committed and one which sought ways of avoiding punishment for the fact that it had” (Kemp 2007, p. 57). And although being devoured by Ammit and eliminated from Eternity was a theoretical possibility, in practice no one ever reported that as his or her fate. Needless to say, it would not have been a good career move for a scribe to record the failure of a pharaoh to be judged worthy, and no commoner would have spent six months’ income on a papyrus that ended on such an unhappy note. Nonetheless, the possibility of failure did exist, and the Egyptians took that very seriously. The funerary texts were there to provide protection by instruction.

The shortcoming people feared most was failure to do their part in upholding order in Egypt and therefore in the cosmos: the violation of maat. They knew of such people — they were the mutu, “the damned,” people who had been executed as enemies of the state (Taylor 2010, p. 23). Therefore the Second Death was a real concern, and in this balance of cause and effect, the cause was clear: the mutu had committed the worst possible sin — they had been enemies of order.

All along, we have been seeing how myth steps in to support an idea. One of the foundation myths of Egypt is the dispute between Seth, representing chaos, evil and barrenness, and his brother Osiris, representing order, goodness and fertility. There is no good without the possibility of evil, no order without the threat of chaos, no life without both male and female principles: so this duality must exist. Ammit the Devourer had to be taken seriously as an idea even if the theoretical threat she represented could be circumvented.

So now we have a practical sense of how order was to be maintained on Earth: morality and ethics. Cosmic order (maat) had its earthly complement in earthly order and justice, in doing right, maintaining ethical behavior — decency, honesty, fairness, moderation, charity, goodness and right living. And these ethical principles were well covered in the 42 petitions of the Negative Confession: the life you led on Earth would be examined and judged at the Weighing of the Soul. Preservation of order was an obligation of the living. “There was no declaration of religious belief, no test of faith…. What counted was how you behaved and not what you believed” (Kemp 2007, p. 54). The secular texts of the Middle Kingdom — the Wisdom Texts, the Instructions — had applied ethical considerations to the maintenance of social order. Now the Book of the Dead puts all that on the grand stage in the Hall of Judgment, as religion.

In Part 5 we will go on along with the Blessed Dead, and explore their eternal home: the tomb, and its meanings.

Photo credits

All photographs by Brian Alm unless otherwise stated.

References

D’Auria, Sue, Lacovara, Peter and Roerig, Catharine H. 1988, Mummies & Magic: The Funerary Arts of Ancient Egypt. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Dodson, Aidan and Ikram, Salima. 2008, The Tomb in Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London

Goelet, Ogden. 1998, commentary in The Egyptian Book of the Dead (R. O. Faulkner, O. Goelet, tr.; Eva von Dassow, ed.), Chronicle Books, San Francisco

Hawass, Zahi. 2007, Pyramids. White Star, Vercelli, Italy

Kemp, Barry. 2007, How to Read the Egyptian Book of the Dead, W.W. Norton & Co., New York

Lichtheim, Miriam. 2006, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Vol. II. University of California Press, Berkeley

Shaw, Ian, ed. 2000, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford U.P., New York

Taylor, John H. 2010, Journey through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, Harvard U.P., Cambridge, Mass.

Teeter, Emily. 2011, Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge U.P., Cambridge

Time-Life Books (editors). 2004, What Life Was Like on the Banks of the Nile. Caxton Publishing, London

Wilkinson, Toby. 2008, Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, London

Author’s Note: No one should attempt to understand ancient Egypt by reading just one book, or even a shelf of them, but if I were pressured to recommend just one, or two, books for a study of the Book of the Dead specifically, they would be Taylor’s Journey through the Afterlife and, as a necessary companion volume, Kemp’s How to Read the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

By

By