Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 4, February 27th 2012

By Andrea Byrnes

Part 2 – The cultural context

Introduction

In Part 1 the political background to and development of the Third Intermediate Period was described, emphasizing the way in which power became divided, both within the Delta and between the Delta and the south, where the Theban high priests became increasingly powerful. Part 2 looks at the blending of Libyan and Egyptian traditions, with new ideas expressed in funerary practices and in the role of religious institutions.

Libyan or Pharaonic Traditions?

Throughout the 22nd Dynasty the Libyan Meshewsh rulers clearly retained pride in their Libyan origins, continuing, as they had done in the 21st Dynasty, to refer to themselves as the “Great Chiefs of the Ma,” (“Ma” being short for Meshwesh) and had distinctive non-Egyptian throne names. Although their affiliations to their Libyan past were explicit, they adopted many Ancient Egyptian customs. It is clear that they saw no need to reinvent the administrative wheel and continued to maintain the existing system (Kemp 2006), whilst using a localized version of hieratic for documentation. Although their throne names appear to have Libyan origins, their prenomens were Egyptian, albeit somewhat contrived.

Thebes was far more obviously traditionally Egyptian in style and tone, thanks to the cults of Amun, Osiris and other important deities. Even on a local level it is clear that Theban people continued to adhere to the old cults. In Thebes, throughout the upheavals, existing cults were maintained. During the 22nd Dynasty and at the beginning of the 23rd Dynasty, while Amun continued to be dominant, small chapels to Osiris were built to the north of the Temple of Amun in Karnak. Under the reign of Osorkon II two rooms and a small forecourt made up the chapel Osiris Wep-Ished, now known as Temple J (Blyth 2006). Osorkon III erected another temple dedicated to Osiris “Ruler of Eternity” at Karnak, which is still quite well preserved. At the time it was outside the temple enclosure but was given a mud-brick wall with a stone entrance.

From domestic contexts small statues and stelae survive, all copying the Pharaonic style quite faithfully. Requests to the deities for assistance and memorials to the ancestors continued to be made.

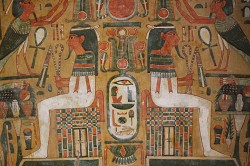

Paintwork on coffins and on stelae is some of the brightest and most beautiful to be found in museum collections. The colours are vibrant and the themes are traditionally Egyptian.

In the service of Amun at Thebes

By the Third Intermediate Period the Priesthood of Amun, which had been powerful throughout most of the New Kingdom, now had an overtly political component to it. At the beginning of the 22nd Dynasty Sheshonq I devoted considerable attention to Karnak, building a forecourt in front of the Second Pylon, a project managed by his son the High Priest of Amun Iuput, and designed by the architect Horemsef (Blyth 2006). Other 22nd Dynasty kings made smaller alterations to the temple.

The most senior position in the priesthood of Amun was the High Priest or First Prophet based at the Temple of Karnak. He was also the most important person in Thebes, second only to the king, and at times equal to him. The role of High Priest was supposed to be appointed by the king and the incumbent was usually a senior army general, as in the above-mentioned example of Iuput. Another king’s son from the 22nd Dynasty who was also High Priest was Prince Osorkon, son of Takelot II, who combined the role with that of Crown Prince, army leader and Governor of the South. As well as being responsible for controlling most of Upper and Middle Egypt, the High Priest was responsible for running the vast religious estates held by Karnak, and overseeing a vast staff of priests and administrators who managed day to day running of the Temple including the offerings to and rituals for the deity, and his oracle proxy and the maintenance of the fields and livestock belonging to Karnak.

Directly beneath the High Priest was the Deputy High Priest (or Second Prophet). The priesthood beneath them consisted of a complex and elaborate hierarchy that is still not entirely understood, but consisted of both male and female participants.

Of the female members of the priesthood the singers were the most numerous. The position of singer dated back to the Old Kingdom and by the Third Intermediate Period there were a number of different ranks of singer serving the cults of Amun, Osiris, Isis, Mut and other deities. By the 22nd Dynasty there were ranks of singer in the priesthood. The position of ‘Singer in the Interior of the Temple of Amun,’ which seems to have been particular to the 22nd through 26th Dynasties, was the most senior, and many who held the title were princesses or the daughters of mayors or other very senior members of Theban society. If they did indeed have access to the inner temple, an area restricted to the most senior members of the priesthood, their status was considerable. The lowest position was apparently the “shemayet,” a position that was confined to elite family members but was so frequently represented “that it seems that most households had members who were singers” (Teeter and Johnson 2009, p.26). Graves-Brown suggests that they were lay priestesses (2010). The positions were non-hereditary but family connections were clearly important although singers were able to work their way into more senior positions. Each rank had an overseer who was responsible for them, the head of whom in the Third Intermediate Period was the “God’s Wife of Amun.” The singers of the priesthood would serve as a choir when the priest was carrying out rituals, when the god (in the form of a statue) travelled and when festivals were held. Deities were thought to enjoy and be calmed by the sound of music, and musicians often played at funerals. The sistrum rattle had an especial magical role in the pacification of certain deities.

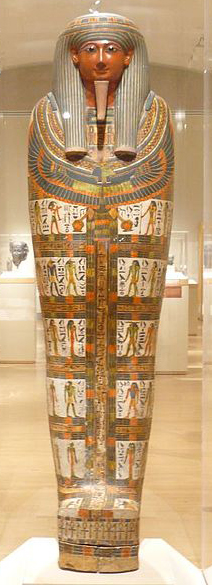

Thanks to the 2009 exhibition held by the Oriental Institute in Chicago, the best known “Singer in the Interior of the Temple of Amun” is Meresamun, a 22nd Dynasty priestess in the reign of king Sheshonq III (Teeter and Johnson 2009). Although her genealogy is not recorded, and her coffin is unprovenanced, the coffin is very well crafted and its voluminous paintwork is skilled and beautiful, reflecting the prosperity and prestige of Meresamun and her family. Nehmes-Bastet’s burial in the Valley of the Kings demonstrates the social status of singers and offers a valuable provenanced and seemingly complete burial.

Funerary Traditions in the 22nd and 23rd Dynasties

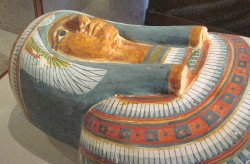

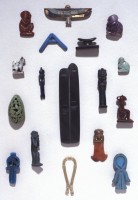

The funerary traditions of the 22nd and 23rd Dynasties were much less elaborate than those of previous periods, apparently demonstrating far less of an investment in the afterlife. Although individuals continued to be mummified and provided with coffins, there was far less emphasis on grave goods, which were usually limited to canopic jars, shabti figures (often in large numbers) and a single painted stela to Ra-Horakhty or, less commonly, Osiris. The mummified form was usually adorned with several amulets. Instead of tomb decoration, the coffins and cartonnage cases of many of the mummies were often painted in bright colours with elaborate scenes of typical Pharaonic subjects.

Apart from Amun the main deities to be highly regarded appear to have been Re-Horakhty, Sokar-Horus and Osiris, although many of the other Pharaonic deities still received attention.

Djanet (Tanis)

The Libyans in the north interred their royalty in tomb constructions completely distinct from any previous royal tomb forms, although their burials included Pharaonic elements. Although the tombs of the earliest 22nd Dynasty rulers (Shoshenq I and Osorkon I) have not been found, a number of other royal burials were located, together with tombs from the 21st Dynasty, by Pierre Montet in 1939. They were all located within the complex of the Temple of Amun in Djanet, rather than in the broader funerary landscape favoured by the Thebans.

Superstructires have survived for none of the royal tombs at Djanet, although elements of the substructures are now above the land surface. Strudwick and Strudwich suggest that the superstructures would have consisted of a pylon gateway, a small courtyard and a chapel (1999). Tombs were communal, containing not only royal family members but favoured individuals from the elite. The sparse tomb paintings often included the “Weighing of the Heart” scene from the Book of the Dead, previously known only from private tombs. No new mortuary texts were introduced. The only innovation was the identification of the dead person with the combined deity Sokar-Osiris and this was reflected in some burials where sarcophagi, instead of displaying human heads, were in the form of falcon heads (e.g. Sheshonq II and Talelot I). In their entirety the early Third Intermediate version of funerary practices formed a very different funerary model from that favoured by the New Kingdom rulers (Taylor 2010).

The earliest of the Djanet burials found by Montet is that of Osorkon II the 21st Dynasty sepulchre of Nesibanebdjedet I (NRT-I). The tomb also housed Osorkon II’s father Takelot I and his sons Takelot II and Prince Harnakhte C. The tomb was decorated with themes common in the 18th Dynasty including scenes from the Book of the Dead and the Amduat. Although the tomb had been thoroughly robbed, the remarkable quartzite sarcophagus of Takelot II remained, together with hundreds of shabtis and alabaster jars.

Sheshonq III, who succeeded Osorkon II, was buried in a very simple tomb (NRT-V) consisting of a small chamber with a half-dividing wall, and was decorated with scenes from the Amduat and “various less usual scenes and vignettes from the Book of the Dead” (Dodson and Ikram 2008, p.275).

Sheshonq IV was buried in the tomb of Sheshonq III (NRT-V). The following ruler, Pimay, was buried in a simple tomb (NRT-II) that was as simple as Sheshonq III’s but was undecorated. Sheshonq V was buried in the earlier tomb of Osorkon II.

The 1939 excavations also revealed, in tomb of the NRT-III, belonging to Pasekbkhanut (Psusennes) I, the existence of a king named Sheshonq II who had not previously been identified. Sheshonq II seems to have been removed here from another tomb (Dodson 1994), and was buried in a remarkable silver falcon-headed coffin within which his mummy was undisturbed, had a gold mask over its face, and was accompanied by elaborate and beautiful bracelets and pectorals made of gold and set with jewels and coloured stones. It is not quite clear exactly where in the sequence of kings Sheshonq II lies. The mummy of Sheshonq II was examined by Douglas Derry in 1939 who noted that the brain had been removed from the skull, as in traditional Pharaonic burials. The tomb later produced the remarkably rich undisturbed tomb of Pasekbkhanut (Psusennes) I of the late 21st Dynasty.

Private elite burials connected with the Delta rule, elsewhere in Egypt, showed very similar features as those of the royal family, suggesting “a blurring of distinction between royal and high elite burials” (Taylor 2010, p.226).

Thebes (Luxor)

Whether the general populace felt strongly about their religious institutions is difficult to tell, and at least a portion of society had, from the late 19th Dynasty onwards, rejected the threat of curses and the law and desecrated tombs in the Valley of the Kings. But the cult of Amun remained a powerful force in Upper and Middle Egypt and various cults continued to be observed, whilst members of the elite were buried in a simplified version of Pharaonic traditions.

Some High Priests were buried in the Valley of the Queens. Many others were found in a tomb near the temple of Hatshepsut known as the Bab el-Gasus, all highly decorated.

For private burials, different areas were favoured at different times. For individuals in the 21st Dynasty the Deir el Bahri area was favoured. Later on, the Ramessum area was preferred. By the 23rd Dynasty the site of Hatsheput’s Mortuary temple, now covered with debris, was chosen for tombs (Strudwick and Strudwick 1999). Unfortunately the sites around the Ramesseum are poorly preserved and have been badly robbed, depriving them of much of their value as a source of data, although it is clear that some tombs were used for different generations of the same family (e.g. the intrusive 22nd Dynasty burial in the 18th Dynasty tomb of Sennefer, TT99).

Tombs in existing rock-cut tombs of the Middle and New Kingdoms were reused. Intrusive burials occur all over the Theban necropolis, in the Theban Valley (the Valley of the Nobles), as well as in the Valley of the Kings. The intrusive burials of this period tend to be simple. Wooden coffins may be lightly decorated and encase mummified bodies that were sometimes provided with anthropoid cartonnage cases. Few, if any, grave goods are provided to accompany the deceased, a development may be connected with the reduced prosperity of Egypt, but may equally reflect new ideas about the afterlife.

The New Kingdom Tomb of Sennefer in the Valley of the Nobles at Sheikh abd el Qurna (TT99) was re-used in the 22nd or 23rd Dynasty by at least one family. The style of fine painting on one early 22nd Dynasty cartonnage mummy case dating to c.900 BC names one Djedhoriuefankh, and texts on two other wooden coffins in the tomb belong to two of his children (Taylor 2000). The remains of cartonnage in the tomb showed that the mummy cases were not built up around the wrapped mummy in the style of some mummy masks of the period “but were fashioned over a core of mud and straw, which was removed before the mummy was inserted” (Taylor 2000). The layers of linen that formed the cartonnage, up to 15 layers in one case, were soaked in glue or plaster to form a solid case. The mummy case of Tabakmut, shown on the TT99 website, shows a case very much in the style of earlier anthropoid coffins, with bright paintings of deities and familiar motifs. All of the wooden coffins in the tomb were anthropoid and given small amounts of decoration. No grave goods are recorded.

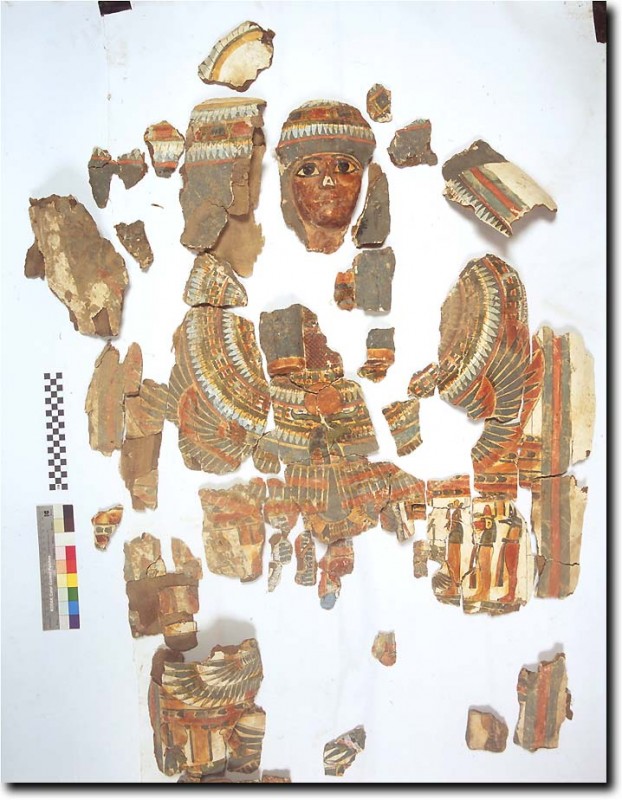

In the Valley of the Kings, both KV4 and KV45 received intrusive burials from the 22nd Dynasties (Reeves 1996). The only remains from KV4, the tomb of Ramesses XI, are the burnt remains of a 22nd Dynasty burial consisting of fragments of cartonnage coverage and a wooden coffin. KV45, the 18th Dynasty non-royal tomb of Userhet, consisted at its discovery of a single chamber full of rubbish, and produced the remains of two 22nd Dynasty mummies each in a double coffin. Donald Ryan’s excavations produced the fragmented remains of 44 roughly made mud-formed shabtis and a small limestone scarab. Although the remains are badly water damaged a cartonnage representation of a man’s face survives. The remains of four individuals were found, that Ryan interprets as a mixture of two original occupants of the tomb as well as the two intrusive burials (Ryan 1992). Reeves suggests, on the basis of faint graffiti at the entrance to the tomb that KV57 may have been used as a cache during the Third Intermediate Period (Reeves 1996, p204).

In the Western Valley the tomb of the pharaoh Amenhotep III (KV22) was excavated by Howard Carter, who found several fragments of late burials that Reeves and Wilkinson suggest are the remains of a king of the later 22nd Dynasty (1996, p.115). WV24, with a deep shaft dropping in to a roughly cut room, also produced remains thought to belong to the 22nd Dynasty, including the fragments of a child’s wooden coffin, fragments of cartonnage, mummy linen and human remains. The tomb is thought to have belonged originally to an unidentified individual of the late Eighteenth Dynasty.

Some tombs were modified, in some cases, for the new users: “New shafts were sunk in the courtyards of these tombs and inside the cult chapels; these shafts again led to small champers accommodating only two or three burials” (Taylor 2010, p.228). Elsewhere brick built chapels and tombs west of the Ramesseum and at various places in the Assasif area “appear to have been constructed in the forecourts of older private tombs” (Strudwick and Strudwick 1999). Taylor says that there is no visible rationale determining the usage of old tombs, with no evidence indicating that the Third Intermediate occupants were related to the original tomb owners (2010).

The arched storage vaults at the Ramesseum were employed for the building of new tombs, again consisting of small burial chambers reached by shafts. They seem to have been accompanied by small brick-built chapels, some with stone fittings, some with decoration similar to that in Ramesside tombs. One of the tombs in the Ramesseum, the tomb of Nakhtefmut (Ram88), has reliefs showing scenes from funerary texts and one fragment (Philadelphia E1824-6) shows the tomb owner’s daughter Djedmutiusankh. Both the art and the hieroglyphic scripts are very much in the style of the New Kingdom. Throughout the rest of Thebes burials of officials continued to be made in older tombs during the entire period: “In many cases this happened repeatedly, with one generation cleared out to make way for a new one” (Dodson and Ikram 2008, p.275).

In the 21st and early 22nd Dynasty coffins were often beautifully painted, with one or two outer coffins often containing an inner coffin of painted cartonnage (made of linen, glue and plaster) that closely moulded the form of the mummy. As with tomb Ram88 the themes were traditionally Pharaonic. On the coffin of Meresamun, for example, are beautifully rendered images of the four Sons of Horus, Ra as a falcon, Wepwawet, Apis and various symbols including Wedjat eyes, the Isis knot, the Djed pillar and the hieroglyphs for eternity, life and dominion (Teeter and Johnson 2009). Coffin design became simpler as the 22nd Dynasty proceeded.

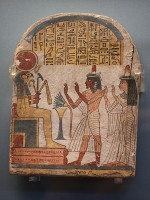

Grave goods were limited to papyri containing scenes from the Book of the Dead (often contained within the coffin), amulets within the mummy’s bandages, canopic jars (often empty), and an often large numbers of shabtis. A wooden stela often accompanied the dead, showing the deceased offering to a deity, usually Ra-Horakhty or, less often, Osiris.

In the case of the mummy of Meresamun earlier traditions of mummification seem to have been partially maintained (Teeter and Johnson 2009). The brain was removed, the abdomen was emptied via an incision in the usual place, and the void was packed. Limbs were wrapped separately, with arms to the side and then the entire body was bound together to create a single mummified form. Amulets were sealed in the wrappings. However, new treatments were also employed during the 21st Dynasty, most of which were continued during the 22nd Dynasty (Taylor 2010). These included packing materials beneath the skin to reduce the impact of the process of desiccation, cosmetic procedures including the insertion of artificial eyes and the painting of the skin (yellow for women and red for men), and the re-insertion of the body’s organs, wrapped, into the stomach cavity. Taylor concludes that “restoring the physical integrity of the corpse had assumed a greater importance than before” (2010, p.232). After the 22nd Dynasty many of these innovations were abandoned.

Instead of funerary chapels, the cult temples of deities now took on a funerary role as well, with statues of non-royal individuals now erected in the temples as the focus of offerings.

There were no more elite burials in Thebes after the 23rd Dynasty.

KV-64 – Nehmes Bastet

Nehmes-Bastet was a Chantress of Amun, the daughter of a priest of Karnak. She was, therefore, very much a product and member of the controlling elite in Thebes.

The coffin of Nehmes-Bastet was intrusive, occupying an earlier tomb. As we have seen, the idea of re-using earlier tombs and monuments was a common one even amongst the Royal family in Djanet, where earlier New Kingdom components were re-used by the Libyan rulers. In the 21st, 22nd and 23rd Thebes the re-use of earlier tombs was standard practise.

KV64, a roughly hewn room at the bottom of a shaft, is thought to have been made during the 18th Dynasty. It was provisionally located during survey work conducted by the University of Basel in January 2011 and confirmed in January 2012 when the shaft was cleared. The walls of the tomb were bare rock with unrefined surfaces.

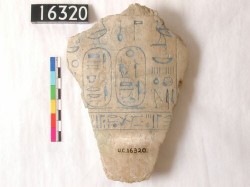

The wooden coffin of Nehmes-Bastet was the first major discovery after the tomb was opened. The 18th Dynasty layers of the tomb have yet to be investigated, but the presence of the 22nd Dynasty coffin was announced to the media in January 2012. Photographs showed a rather roughly carved wooden mummiform coffin with a sculpted face, painted with large hieroglyphs that identified the coffin’s owner as a woman named Nehmes-Bastet. The coffin was accompanied by a small painted stela. When the coffin was opened an undisturbed mummy was found. No decoration of the tomb itself had been attempted in the 22nd Dynasty.

The nationality of Nehmes-Bastet is not yet known. Although her name is Egyptian, the reference to the feline deity Bastet indicates possible affiliations to the north, where the cult centre of Bastet was based. It is possible that Nehmes-Bastet either had Libyan genealogy, had married into the royal family or that her name was chosen to indicate loyalty to the northern kings.

Until more details about the hieroglyphs on her coffin and the painted stela are revealed, it is not possible to know what sort of rank she held as a singer within the temple of Amun.

Her burial was modest, but was broadly consistent with other private burials of the time: she was interred in a tomb created for someone else and had very few grave goods, but her coffin was anthropoid, she was mummified and she was accompanied by a small painted stela . It is clear, however, that although the 22nd and 23rd Dynasty private tombs were never elaborate, Nehmes-Bastet’s was less elaborate than some others. She was not buried, for example, with one of the lovely painted cartonnage cases that characterized Meresamun and the individuals interred in TT99, and nor was the art-work on the outside of her coffin particularly fine. The stela, only partially visible in the photographs released to the press, may correct this view slightly when published.

Like other burials throughout Egypt at this time, some of the conventions of Pharaonic Egypt are maintained in this simplified form.

CT Scans of the mummy itself will undoubtedly be carried out at some point in the future, and may give new information both about methods of mummification employed at this time, any items concealed in the bandages, and details about the physical form of Nehmes-Bastet herself.

Conclusions

Nehmes-Bastet lived in a time of political fragmentation, when Libyan rulers held sway in Djanet and possibly had influence in Thebes as well. Both Libyans and local Egyptians seem to have maintained many of the same administrative systems, and continued to observe at least some of the cults that had been established in the previous 3000 years. Although ideas of an afterlife no longer required vast quantities of grave goods, some individuals still copied the Book of the Dead onto their tomb walls, and the practise of mummification was observed in most cases. In accordance with those modified beliefs, the family of Nehmes-Bastet buried her in the Valley of the Kings in a tomb built for and probably occupied by someone who had died 1000 years before her.

The evidence for the period is still very much open to interpretation and scholarly debate. The account provided in parts 1 and 2 has simplified matters considerably in order to provide a coherent account, but readers wanting to learn more about the complexities of the Third Intermediate Period are referred to the bibliography for more detailed analyses.

Appendix 1 – the Succession of Reigns

From the Digital Petrie website

http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/chronology/3rdintermediateperkings.html

Dynasty 21 (1070/69-946/945 BC)

- Nesbanebdjed (Greek Smendes) (1070/69-1044/43 BC)

- Amenemnisut (Greek Nephercheres) (1044/43-1040/39 BC)

- Pasebakhenniut I (Greek Psusennes) (1044/43-994/93 BC)

- Amenemipet (Greek Amenophthis) (996/95-985/84 BC)

- Osorkon (Greek Osochor) (985/84-979/78 BC)

- Saamun (979/78-960/59 BC)

- Pasebakhenniut II (Greek Psusennes) ( 960/59-946/45 BC)

The high priest of Amun in Thebes

- Piankhi

- Herihor

- Pinodjem I

- Masahalot

- Djedkhonsjufankh

- Menkheperre

- Smendes II

- Pinodjem II

- Pasebakhenniut (Greek Psusennes)

Dynasty 22 (946/45-about 735 BC)

- Sheshonq I (946/45-925/24 BC)

- Osorkon I (925/24-about 890 BC)

- Takelot I (about 890-877 BC)

- Sheshonq II (about 877-875 BC)

- Osorkon II (about 875-837 BC)

(after Osorkon II Egypt is no longer united: several kings still rule from Tanis, the others in Upper Egypt)

- Sheshonq III (about 837-798/785? BC)

- Sheshonq IIIa (about 798-785 ? BC)

- Pamui (about 785-774 BC)

- Sheshonq V (about 774-736 BC)

The Upper Egyptian line

- Horsiese (about 870-850 BC)

- Takelot II (about 841-816 BC)

- Padibast (about 830-80/800 BC)

- Iuput I (about 816-800 BC)

- Sheshonq IV (about 805/00-790 BC)

- Osorkon III (about 790-762 BC)

- Takelot III (about 767-755 BC)

- Rudamun (about 755-735 BC)

- Ini (about 735-730 BC)

Dynasty 23 (818-715 BC)

(a term from the Hellenistic kinglists, applied by different Egyptologists to different groupings of kings: it is used here for numerous local kings of the late ninth and eighth centuries, not ruling from Tanis, whose rulers form the Twenty-second Dynasty, or from Sais, whose rulers form the Twenty-fourth Dynasty)

- Padibast II (in Bubastis/Tanis) (about 756-732/30 BC)

- Iuput II (in Leontopolis) (about 756-724 (?) BC)

- Osorkon IV (about 732/730-722 BC)

- Psammus (?) (about 722-712 BC)

Dynasty 24 (727-715 BC)

- Tefnakht (about 740-719/17 BC)

- Bakenrenef (Greek Bocchoris) (about 722-712 BC)

Bibliography

Please note, additionally, that a new Facebook page dedicated to the Third Intermediate Period was launched in February 2012 (http://www.facebook.com/groups/239832019441502/) in which Aidan Dodson announced that his new book on the Third Intermediate is to be published sometime after mid March 2012. It is entitled: Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance (American University in Cairo Press). His comments about it imply that it will challenge some of the existing interpretations.

Blyth, E. 2006

Karnak: Evolution of a Temple

Routledge

Derry, D.E. 1939

Note on the Remains of Shashanq

Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 39 (1939), p.549-551

Dodson, A. and Ikram, S. 2008

The Tomb in Ancient Egypt

Thames and Hudson

Graves-Brown, C. 2010

Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt

Continuum

Grimal, N. 1988 (English translation 1992)

A History of Ancient Egypt

Wiley-Blackwell

Kemp, B. 2006 (second edition)

Ancient Egypt. Anatomy of a Civilization

Routledge

Kitchen, K.A. 1996 (second 1986 edition, reprinted with new preface)

The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC).

Aris & Phillips Limited.

Manley, B. 1996

The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt

Penguin Books

Murnane, W.J. 1983

Penguin Guide to Ancient Egypt

Penguin Books

O’Connor, D. 1983

New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period

In Trigger, B.G., Kemp, B.J., O’Connor, D. and Lloyd, A.B. Ancient Egypt: A Social History

Cambridge University Press

Reeves, N. and Wilkinson, R.H. 1996

The Complete Valley of the Kings

Thames and Hudson

Ritner, R.K. 2009

The Libyan Anarchy. Inscriptions from Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period

The Society of Biblical Literature

Robins, G. 1997

The Art of Ancient Egypt

The British Museum Press

Ryan, D. 1992

The Valley Again

KMT 3(1), Spring 1992, p.44-47

Schaden, O. 1991

Preliminary report on clearance of WV–24 in an effort to determine its relationship to royal tombs 23 and 25

KMT 2(3), 1991 p.53-61

Strouhal, E. 1992, 1996

Life of the Ancient Egyptians

Liverpool University Press

Strudwick, N. 1997-2010

Re-use of TT99 in 22nd and 23rd Dynasties

http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/tt99/history/reuseD22.html

Strudwick, N. and Strudwick, H. 1999

Thebes in Egypt. A Guide to the tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor

British Museum Press

Taylor. J.H. 2000

Coffins and cartonnage cases

Website: The Tomb of Senneferi, Theban Tomb 99

http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/tt99/report00/coffins.html

Taylor.J.H, 2003 (third edition)

The Third Intermediate Period, from The Oxford Hisory of Ancient Egypt,

In Shaw, I (ed.) 2003, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt

Oxford University Press

Taylor, J.H. 2010

Changes in the Afterlife

In: Wendrich, w. (ed) 2010. Egyptian Archaeology

Wiley-Blackwell

Teeter, E. and Johnson, J.H. 2009

The Life of Meresamun: A Temple Singer in Ancient Egypt

Oriental Institute Museum Publications

https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/pubs/catalog/oimp/oimp29.html

Wilkinson, T. 2010

The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. The History of a Civilization from 3000BC to Cleopatra

Bloomsbury

University of Basel 2012a

Press Release, 22nd January 2012 (in English)

http://aegyptologie.unibas.ch/forschung/projekte/university-of-basel-kings-valley-project/report-2012/

Last checked 15th February 2012

University of Basel 2012b

Video of the opening of the coffin on Video Portal:

http://www.videoportal.sf.tv/video?id=d038af77-abd0-4b27-9bc3-9694887eb104

Last checked date

By

By