By Andrea Byrnes. In Magazine Articles on Egyptological. April 3rd 2012.

Introduction

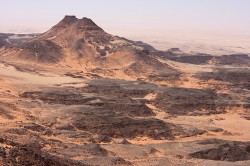

Rising 300m above the desert floor, and covering an area the size of Switzerland, the Gilf Kebir is one of the most arid and inhospitable places in the Sahara. Located in the Egyptian Western Desert, near the Libyan border a 100km north of Sudan, it shares a latitude with Abu Simbel (figure 1). For over 100,000 years the Gilf Kebir was home to generations of hunters, followed by two thousand years of use by nomadic herders, between around 4300 and 2500BC. It was only re-discovered in 1926, and since then it has been the subject of numerous expeditions for exploration, archaeological and geological investigation and, more recently, tourism. Very remote and arid, it remained an almost pristine landscape until recent decades, perfect for field research. Even NASA researchers have studied the Gilf Kebir to evaluate conditions that might prevail on Mars.

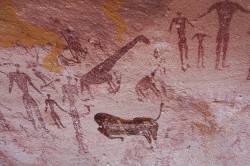

Although there are rich remains from before the last glaciation, this article looks specifically at the post glacial period when the southern Saharan areas emerged from hyper-aridity to produce Sahelian and savannah conditions of shrub, grasses and rough pasture, with summer rains moving north into Egypt in Gilf Kebir c.8200 to 2700BC. Vegetation emerged, attracting herds of wild animals. Hunters followed them and settled into patterns using the Gilf Kebir as part of much larger territories. Some groups eventually adopted newly introduced domesticated animals that could be herded over large areas but required major changes to economic, logistical and social practices. As well as ephemeral settlement remains, consisting of hearths, large numbers of stone tools, and remnants of meals, some of the groups who moved through the landscape of the southwest Western Desert left beautiful rock art in caves and shelters, both engraved and painted (figure 2).

The people represented by these four periods were Homo sapiens sapiens, like us. Although without our knowledge and resources they had our same basic needs and desires, practical and technical skills, the ability to learn, exchange knowledge and adapt to change, and the skill to build and maintain long distance social connections.

The Character of the Gilf Kebir

The Gif Kebir consists of two plateaus, divided by a gap which has become sand-infested. Both plateaus are laced along their eastern edges with wadi systems (dried up river valleys), sometimes several kilometres long. The western side towards the greater Sahara presents the appearance of an impenetrable wall. To the north the cliffs are being subsumed by the ever shifting sands of the Great Sand Sea. Geologically, it is composed of Nubian Sandstone with occasional volcanic intrusions, the entire plateau sitting on the considerably ancient Pre-Cambrian basement complex.

Figure 3. Vegetation is very sparse on the plateau of the Gilf Kebir, but small shrubs and desert adapted plants still survive

The Gilf Kebir lies in the eastern Sahara in a part of the desert known either as the Libyan Desert or, in Egypt, the Western Desert. Today it has no freshwater supplies, and its vegetation and sparse wildlife depend on the 2-5mm annual rainfall for survival. Some woody species still survive in the bases of a few wadis, including Acacia, Balantes and Maerua, but these are few and far between (figure 3). Some small shrubs and plants seem to survive. After rainfall, however, around 15 species of ephemeral grasses spring to life, providing remarkable levels of coverage of the plateau and wadi floors. It supports a staggering amount of unlikely wildlife including desert foxes, gerbils, gerboa, reptiles (including lizards, scorpions and snakes), and a wide variety of insects (including locusts, beetle and butterflies). When you wake up in the morning in a desert campsite in the most remote area you will find your tent surrounded by tiny tracks. Before they were hunted out in modern times, the Gilf wadis and plateaus still supported Barbary sheep.

The desert surrounding the southern Gilf Kebir is marked with seismic and meteoric craters and the ground is littered with basalt, lava bombs, fossils, strangely shaped remnants of former lake sediments (yardangs) and prehistoric objects including stone tools made on silicified sandstone, grinders, mortars and fragments of ostrich eggshell. Although it is largely barren today, it supports the same range of fauna, although more sparsely, that inhabits the Gilf Kebir itself.

Consequences of finding the Gilf Kebir

The rediscovery of the Gilf Kebir and its subsequent exploration is an attractive story, the subject of a number of books, academic papers and articles. It was identified in modern times by a team sponsored by Prince Kemal el-Din, the son of former Khedive Hussein and cousin to Prince Farouk, who gave it the name Gilf Kebir (Great Barrier). The Prince furnished his team with Citroen Kargasse vehicles equipped with caterpillar tracks, like tanks, and accompanied by a camel train. He was accompanied by the tiny and almost deaf geologist John Ball who had previous experience of the Western Desert both as a member of the Light Car Patrols in the First World War and as a veteran of several exploratory expeditions. They reached the Gilf Kebir in 1926. In an era of successful Libyan Desert explorers, this was no small achievement.

The discovery of the Gilf Kebir sparked a revival of interest in the legend of Zerzura. Zerzura was a centuries-old legend but was best known from the 15th Century Arabic “Book of Pearls,” a treasure hunting guide which describes the lost oasis of Zerzura, where huge gates open into a world of jewelled wealth where the king and queen sleep eternally. In the 1830s Sir John Gardiner Wilkinson was told the story whilst he was staying in Dakhleh Oasis and published an account of the legend, bringing it to the notice of a wider Western audience, including military officer Ralph Bagnold.

Bagnold was one of many British army officers stationed in Cairo with time on their hands. Whilst others entertained themselves in Cairo, Bagnold and his friends began to explore the Egyptian deserts, braving the extreme desert conditions in a Model T Ford. Learning from their initial forays and devising technical and operational solutions to enable them to go further, they made huge advances in desert travel, and with his companions Bagnold advanced deep into the Western Desert, conquering the vast and seemingly impenetrable dunes of the Great Sand Sea (figure 4).

They soon became so fascinated with the desert that, hearing about the lost oasis, they formed themselves into the “Zerzura Club” a loose affiliation of interested and active members who met on an annual basis to discuss new plans for locating the fabled place, concentrating their efforts on the Gilf Kebir. Acquiring a small biplane they soon identified specific green wadis as possibilities. Having identified rock art and prehistoric remains, they published in popular and academic publications, which sparked the interest of European archaeologists. One of their members was the skilled cartographer Patrick Clayton, who was responsible for producing maps of the Gilf Kebir that are still in regular use today.

One of the first explicitly archaeological expeditions to the Gilf Kebir was led by Zerzura Club member Laszlo Almasy in 1933. He accompanied ethnographer Leo Frobenius and archaeologist Hans Rhotert. They discovered the “Cave of Swimmers,” immortalised in the film The English Patient (figure 5), and multiple prehistoric assemblages. Sadly the collection of items that Frobenius returned to Europe was lost in the Second World War. Another expedition in 1938, this time led by Bagnold, took rock art expert Hans Winkler and archaeologist Oliver Myers to the area. Myers collected a significant collection of stone tools and pottery sherds which were later studied to great effect by William McHugh in the 1970s. Most of the work over the last three decades has been carried out by the University of Cologne.

Figure 6. Desert research is a logistical operation, requiring extensive planning that allows for problems.

Desert archaeology presents a number of challenges. The logistics of a trip into one of the most arid places on the planet are difficult, requiring teams to take all the fuel, food and water that they will need for however long they remain. Cars get stuck in the sand and engine parts suffer from the heat, sand and strain (figure 6). All rubbish must be taken back, and there must be spare cars and kit in case of failures. Working conditions, even in the winter, can be uncomfortably hot, and sand gets into everything – including delicate equipment. Snakes and scorpions are often present. The archaeology itself also presents complications. Deflation, the process by which wind removes sand from desert surfaces, often leaves all artefacts of different ages on the same surface, sometimes making it difficult to tell where one occupation ends and another starts. The same processes revealed faunal remains which, though preserved by the arid conditions, exposes them to the wind and causes them to break up, making them difficult to identify. Rock art, although instantly engaging, is very difficult to date and is therefore often difficult, if not impossible, to tie in with other archaeological data. Finally, tourists have severely depleted some of the richer sites of their more distinctive artefacts, a fact already bemoaned by Bagnold thirty years ago, which means that valuable data has been lost.

Climate and the environment

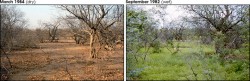

Figure 7. Vegetation in the Sahel follows seasonal rainfall. This is an example from modern Senegal showing the difference between March and September in the same year.

In the wetter early mid Holocene (post-glacial humid period) the monsoonal conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa today extended north into Egypt and subjected the Gilf Kebir to heavy but short summer rainfall, whilst further north the temperate conditions of the Mediterranean presided, with longer periods of lighter winter rainfall. Under the summer monsoonal conditions depressions on the plateaus and the deep wadis which collected rainwater were much better suited to vegetation than today, but the relative poor quality of the soil and the average of only 150mm of rainfall per annum and intensely high evaporation rate meant that these would never be richly populated with either vegetation or fauna, and intense seasonal variation meant that it would only have supported hunters and herders during the rainy season (figure 7).

In two of the eastern wadis of the southern plateau, Wadi Bakht and the Wadi el-Akhdar, both several kilometres long, sand dunes formed natural dams across the wadis, capturing water and creating seasonal lakes. In the Wadi Bakht the lake covered 6600 square metres and surviving sediments reach 10m in depth – it was clearly a considerable water source. Unfortunately the remarkably high evaporation rates in the Western Desert would have depleted it quite rapidly, over a period of several weeks or a few months. Likewise, depressions in the surrounding desert filled with water (called playa lakes), creating seasonal settlement foci for mobile groups. The environment resembled today’s Sahel and savannah conditions. The water table was inaccessible, several 100m below the surface of the plain.

Later, at around 3200BC, the return of the monsoonal zone to more southerly areas brought temperate Mediterranean-type conditions to the Gilf Kebir and areas on the same latitude. This meant the loss of the short but heavy summer rains, to be replaced by longer but less intense winter rains that were more consistent, and fell during the evening and night when evaporation levels were lower. Although they did not fill the playa lakes in the same way, they did provide small pools of water and much larger areas of longer term good quality pasture.

Charred wood remains have produced evidence for the trees that survived during the period of human occupation and includes Acacia, Ziziphus, Maerura Crassifolia, Tamarix and Balanites, all adapted to semi-arid conditions and all useful indicators of the prevailing climate. The two wadis seem to have been used on an alternating basis with long periods of time before switching to the alternate. Linstadter (2002) suggests that this was to allow the recovery of shrubs and small trees, vital for firewood, which implies that although wood was available, it could not sustain human populations indefinitely.

From hunters to herders and back again

The occupation of the Gilf Kebir is divided into four periods, Gilf A, B, C and D (Gehlen 2002) that span the 5000 years when the area was habitable, before climatic downturn forced migration out of the area. Although artefact scatters and evidence of settlements with hearths and tools were found throughout the Gilf Kebir, in smaller wadis (for example Wadi Sura, Wadi Wassa, Wadi Firaq), and a few sites on the plateau, the main concentration of sites is in the two wadis on the eastern side of the southern plateau: the Wadi el Akhdar and Wadi Bakht already mentioned, together with their dune-barrier lakes.

Hunting communities

Post-glacial hunters

From 8300 to 6800BC the climate was favourable for the re-occupation of the desert areas, with short but intensive monsoonal summer rains. The earliest settlements in the Gilf area (Gilf A) are found from 8100BC. Multiple indications of Epipalaeolithic presence are found in the Gilf area. Epipalaeolithic is a term used to indicate a hunting economy, characterised by small blade tools, usually very finely worked, many hafted to form arrows (figure 8). It was the first of the hunting economies to migrate back into the Sahara following the Late Glacial Maximum. Small groups travelled over large distances to take advantage of resources at different times of the year. The Gilf assemblages are typical of the Epipalaeolithic. Best represented at the Wadi el-Akhdar and Wadi Bakht, the toolkit consisted of elongated triangular pieces, slender points with finely worked edges and carefully modified blades. There are numerous similar temporary camps found in the southwest Western Desert at this time.

Hunters with pottery

From 6500 to 4300 BC (Gilf B, sometimes referred to as the Middle Neolithic) the monsoonal conditions persisted, with summer rains continuing to fill local pools and lakes, and filling barrier dunes that crossed Wadi Bakht and Wadi el-Akhdar with deep reserves of water. The ephemeral settlements of these visitors are concentrated in the Wadi al Akhdar and the middle reaches of the Wadi Bakht, concentrated on the dunes around the lake. Only a few sites were found on the plateau and there was a single settlement on the eastern plains.

Settlement sites from this period in this area consist of artefacts abandoned in situ, often accompanied by hearths and animal bones. Different types of artefacts accompany sites of different dates. The sites from Gilf B are particularly large, extending up to 10,000m2, with artefact concentrations of up to 2000 items per square metre. As well as stone and bone tools and pottery, ostrich eggshell beads were made and grinding stones were used.

The hunters who used the Gilf during this period obviously could select from a generous choice of game, including ostrich, desert hare, Barbary sheep and a number of ungulates, like gazelle, antelope and addax. There are notable differences from the earlier Epipalaeolithic including a different type of blade technology and the presence of sherds of pottery.

The stone tools represent a very broad range of activities dominated by small tools, including beautifully standardized and shaped microliths in triangular and trapezoid form, long blades and a few uncharacteristically large tools (figure 9). The level of standardization and the skill required to make these tools was quite labour intensive, an investment of time, indicating the importance of the precise function of these tools as hunting tools, and the range of tools is much more extensive than those left during the Epipalaeolithic. Most of the raw materials for tool manufacture were available nearby on the plateau, and several very small sites have been found near outcrops of quartzite that have been clearly had chunkgs removed from them, less than 1km from the Wadi Bakht, clearly used exclusively used for resource exploitation and tool manufacture.

The pottery, found at nearly all sites and represented by thousands of sherds, has no decoration apart from simple edge notches. It is of a fairly coarse type. Saharan ceramics, predating those of the Near East, are a feature of post-glacial Saharan communities and knowledge of pottery manufacture seems to have spread from the western Sahara to the east, appearing first wherever hunting communities were partially sedentary, living in one area for most or much of the year to take advantage of a broad mix of resources like fishing, hunting and fowling.

The Western Desert was well occupied at this time, coinciding with a hiatus in Nile occupation. The assemblages have affinities with the neighbouring wider areas including the southern Great Sand Sea, eastern areas of southern Egypt and the Selima Sandsheet, giving some idea of what sort of connections these groups had.

Herders who hunted

Labelled the Gilf C period, (also sometimes known as the Late Neolithic) between 4300 and 3500BC this is a period of significant change, introducing domesticated animals into the subsistence economy of groups who used the Gilf Kebir as part of their annual livelihood strategy.

Cattle seem to have been domesticated indigenously in Egypt (e.g. Gautier 2002) , but sheep and goat were imports from the Near East. The earliest evidence of sheep and/or goat in Egypt comes from the Eastern Desert. Sheep and goat are often impossible to distinguish in the archaeological record and are therefore usually referred to by a generic term like ovicaprines, which will be used here. The wild ancestors to domesticated ovicaprines were not indigenous to Egypt, and the earliest domesticates were probably introduced from the Near East, where they are chronologically much earlier. From the Eastern Desert they spread west and south into other areas of Egypt and Africa. Unlike wild fauna of the same size, domesticated animals cannot acquire water through plant leaves during times of stress but must drink water. Cattle require more water than sheep and goat, and require much better pasture, so sheep and goat tend to be favoured in semi-arid and Sahel-type areas where conditions are unpredictable (figure 10).

At this time the monsoonal front was already retreating back to the south, and the intense but brief summer rainfall was replaced with winter rainfall that fell less intensely but more evenly and usually during the cooler parts of the day when evaporation rates were less. There was also less surface run-off, allowing the rain water a chance to saturate the soil. Similarly, the plains around the plateaus would have encouraged winter and spring pastures. These conditions would have favoured a pastoral lifestyle, but it is unclear where these groups acquired their herds and how they were related to the previous hunters, if at all.

The faunal record demonstrates that these groups used a mixture of wild and domesticated species in their diet. The domesticated animals represent a huge change in lifestyle, which will be discussed below. Dominated by sheep and goat, the remains of domesticated cattle have also been found, reflecting images in rock art. The Gilf C visitors also hunted to supplement their diet and preserve their herds for when that meat was actually needed. Their prey includes ostrich, giraffe, desert hare, gazelles and desert fox. Desert foxes, natural scavengers and eternally curious, may have been easy prey.

The Gilf C is initially represented well at both Wadi el-Akhdar and Wadi Bakht but towards the end of the period settlement was only found in Wadi Bakht. It is possible that the Wadi el-Akhdar barrier dune failed at this time, forcing people to move to Wadi Bakht, where it was still in tact. The artefact inventories are found in both of the main wadis, but in smaller concentration. Whereas the big camps of the Gilf B could reach 10,000 metres square in the wadi, those of the Gilf C only reached 100 square metres with a correspondingly low artefact density at each site. Settlements by then are much more widely distributed, both in the playa area, sometimes on the dry play surface, but there were also a much greater number of sites found on the plateau itself, some quite large. The larger sites were clearly not just for material collection but were used for longer term stays, presumably with herds to benefit from new pasture lands. Smaller plateau sites seem to have been used in a similar way to the Gilf B, for raw material collection, but extended much further towards the centre of the plateau. This is a much broader and more skilled use of the different biomes and resources available in the Gilf Kebir, demonstrating a clear understanding of both the seasonal landscape and its advantages to domesticated livestock.

The stone tool kit is much more standardized than that of the Gilf B, and far less labour intensive to produce (figure 11). It consists of a larger and less diverse toolkit with only few microlithic components, suggesting that hunting was much less important. McHugh suggests (1975) that the tools from this phase favour plant-harvesting and wood shaping.

Pottery use continued but with different types of decoration consistent with other areas. Unlike that of the Gilf B it is well fired, thin-walled and decorated either with incised or impressed decoration. A common motif is herringbone patterns made by impressing a comb into the surface of the unfired vessel (figure 11). Fewer desert settlements are found at this time, but new settlements, closer to the Nile, are attested including the Nile-fed Faiyum near Cairo, with a full range of domesticated animals and cereal crops.

The desert returns

The key concept underlying all practices for herders in marginal areas is predictability. If rainfall is predictable in terms of volume and the location in which it falls, local routines will be unchanged, moving to known pastures at known times. If these variables change, however, it may be necessary to move to different areas to find pasture. This sort of occasional variability is common and can be easily factored into a year’s movements. The real challenge comes when variability develops into unpredictability. If rains fail, fall where pasture won’t grow or where land is already claimed by a different kinship network, groups may have to take more unusual measures to manage the new levels of livelihood stress. This may take the form of using food stuffs normally avoided, travelling further afield to find new pastures, reducing stock, or seeking assistance from the wider family and social network. In severe cases drought may occur. A single season of drought will not wipe out a group or its livestock, but repeated seasons lead to long term distress. As drought follows drought the options for sustaining life reduces, and drastic measures need to be taken, if possible, to avoid starvation. The most obvious of these is long distance migration.

When the climate started to become drier by 3200BC, after the collapse of the dune barrier around3300BC, lakes no longer formed and pastures no longer flourished. There were few options available to herders, dependent upon predictable sources of water, who found themselves in the midst of a process of desertification. At Gilf Kebir, thanks to the rainfall attracted by the highland areas, settlement lasted longer than in the surrounding plains, but it could only last so long. Between 3200 and 2700BC, there are some sites belonging to an ephemeral Gilf D. Interestingly, there is a return to a high percentage of microliths, transverse arrowheads, blades and narrow flakes. This suggests that this group, whether connected or not with the previous herders, were largely hunters. There are few remains of what the Gilf D visitors consumed, except for some large mammals, but there have certainly been no remains of sheep and goat located to date, with only possible remains of cattle. Following the Gilf D, the area was abandoned (figure 12)

After the last herders abandoned the area they had a number of options – to move south into the Sudan or Chad, west into Libya, or east to the oases or the Nile. The oases, occupied throughout the humid period and still occupied now, were probably already stretched to capacity. There is no sign of Gilf cultural traits at the Nile.

Communities on the edge

Although the Sahel and savannah conditions of the Gilf Kebir area were capable of supporting human life, it was not always an easy life.

As we have seen, the need to respond to changes, which are marked in marginal areas, led to change in livelihood management and social relationships. Hunting and herding, though sharing some characteristics like mobility and the need to maintain social networks over large distances, had different operational systems.

Hunters

Hunting activity focuses on the acquisition of foods on the hoof, supplemented by plant foods collected in the area of temporary camps. Together the proteins and fats supplied by game and the carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals supplied by plants provided a healthy diet. Where game was readily available on a predictable basis, such as at lake or riversides, hunting groups could be semi-sedentary, but in more marginal areas both herds and hunters were highly nomadic, following well worn routes as part of a seasonal pattern of exploitation. The barrier dunes at the Gilf Kebir would have provided a short respite from ongoing mobility.

In order to maintain the genetic and social integrity of their groups, they will have had connections with other groups, meeting at certain times of the year to exchange goods and marriage partners, but kinship ties can be quite loose. Hunting groups tend to have co-operative skills, although individuals are often required to make independent decisions. Enormous flexibility of behaviour is required in order to balance the needs of co-operative activities with the requirement for self-reliance. The lack of property ownership, communal or individual, means that few political problems arise.

Herders

The reasons for the establishment of pastoralism by hunting groups is not well understood and is much debated. Whilst many of the benefits seem obvious, there are serious downsides too, as with any major change in livelihood management. The major benefits are that cows and ovicaprines are efficient convertors of plant food to stored food (i.e. meat), often consuming plants that humans would either prefer not to consume or are unable to digest. They also represent a reliable stock of protein, dairy products, fat, skins and bone. In modern pastoral societies they usually represent capital and, as such, can become important indicators of status.

On the other hand they require considerable changes in lifestyle and attitude. Instead of following herds and settling in resource-rich areas, concerned only with the welfare of members of the community, herders are forced to consider the welfare of both the community and the herds that support it. Herds require pasture and water. Sheep and goat are more tolerant of poor conditions than cattle, but must still be tended and moved when necessary. Protection and a degree of nurturing are required. Disease can wipe out entire herds, and depending on the specie, can take years to restore to its former state. Concepts of ownership and status attached to the on-the-hoof investment become important. Movements through the landscape change, with groups sometimes becoming divided for parts of the year. Some grazing lands may be shared by some, but not all. Social and kinship networks become immensely important not only for the trade and exchange, but to build relationships of mutual respect and dependency that could be leveraged during times of economic difficulty. The entire dynamic of life was altered.

In Wadi al-Akhdar and Wadi Bakht the archaeological remains point to a mixture of domesticated and wild animals being used. Stone tools were used for hunting, preparing skins, chopping wood and harvesting grain plants. Grains and roots were ground using pestle stones and flat mortars (figure 13), probably cooked with water and herbal flavours to make the types of porridge and sauces common all over Africa today.

The routine of moving through the landscape in marginal areas was also essential for incorporating meetings with other groups into those movements. Similarities between the Gilf Kebir and Gebel Uweinat, 100km to the south, suggest that the two areas were used as a single territory on a seasonal basis with groups shifting during the summer rainfall to take advantage of the lakes, and returning to the Gebel Uweinat area where natural wells would help them to survive the winter dry period. Today the Baragaig of Tanzania cover 16,0002 miles during their annual treck in semi-arid lands.

Beyond ecology and economics

Given the archaeological focus on ecology and the subsistence strategies, it is sometimes difficult to bring such communities to life, but in the case of Gilf Kebir the amazing art work allows us a glimpse of the world through prehistoric eyes. The art is a constant reminder that although artefacts on the ground seem simple and crude, the lifestyles lived by people, their knowledge of the vast eastern Saharan landscape and the economic decisions made during times of rainfall vairablity and pasture availability are anything but simple.

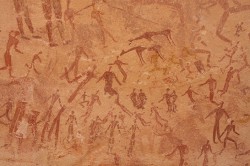

There are two types of rock art in the Gilf Kebir area – the engraved and the painted, both of which offer vivid insights into the world moved through by hunters and herders. It is conventional, in the Gilf area, to consider the engravings as usually, but not exclusively, the earlier of the two forms, and it certainly shows wild fauna – giraffes, horned ungulates like gazelle, antelope, Barbary sheep, bovids and ostriches, sometimes shown in the presence of hunters with canines. Some of the scenes depict the interaction between hunters, hunting dogs and their prey. Others show stand-alone animals or animals in groups. Examples of very fine engravings are found in Wadi Hamra, Wadi Abd el Malik and the Mestekawi-Foggini cave (the latter best known for its painted scenes).

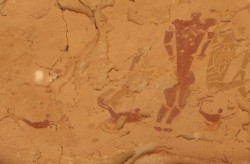

Still undamaged, the wonderful Mestakawi-Foggini cave (also known as Wadi Sura II), was named for its discoverers who found it in 2002 to the northwest of Wadi Sura (figures 14 and 15). Hundreds of painted images, looking as fresh as when they were painted, cover a huge mass of a rock wall, reached by scaling a steep dune. As well as wild animals (dominated by ostrich and giraffe) are negative hand impressions, humans in vast numbers engaged in a variety of activities, and inexplicably odd figures, some based on humans, but the most peculiar based on something that looks like a lion, without heads. See the accompanying Photo Album. There is one similar, very faded, in Wadi Sura. This cave, showing no domesticates, almost certainly predates the introduction of domesticates.

The best known of the rock art is probably the Cave of Swimmers on the east site of the northern plateau, now a shadow of its former self. Discovered in 1933 it is one of four rock shelters identified by Rhotert in the tiny Wadi Sura. It shows figures of all sorts, in yellows and reds and browns, but is named for the curiously shaped little figures who do indeed appear to be swimming across the rock face (see figure 5). Naturally, multiple interpretations have been made of these scenes, some more plausible than others. A few metres away the Cave of Archers, in an even worse state of preservation, has some beautifully painted figures of cattle and shows archers with bows and arrows.

Figure 15. Ostrich at Mestekawi-Foggini, with the form of the main body of the bird suggested by neck, legs and tail rather than actually painted.

The introduction of domesticates also introduced the ideas of property and ownership. Herd ownership is usually concerned with shared resources owned collectively or owned by individual families but herded collectively, so complex social systems build up about the management of these resources and the communal decisions that need to be made around them. Often, spiritual belief and ritual help to bind small communities and formalize social systems. The strange headless animals at the Mestekawi-Foggini cave may well indicate that ideas of a supernatural sort were shared by the groups using the cave.

Nomadic life, even when semi-nomadic, is all about routes, places and connections. Modern herders have a close relationship with their landscape, imbuing special places with their ideas and meanings. At certain times of the year social gatherings are organized between groups who may move over vast distances throughout a year, to renew social networks, exchange information and perform rites of passage, with festivities, celebrations and much enjoyment. The rock art of the Gilf Kebir certainly gives a sense of this life beyond the simple economic routines of everyday life, celebration, endless activity and appreciation of both the natural and spiritual worlds. Even without attempting to interpret the scenes shown, the sense of life being a very vivid place with complex layers of belief and interaction comes over clearly.

It is clear that social links, whether for trade or mutual social support, were indeed maintained over large distances. Distinctive artefact types appearing at sites sometimes 100s of kilometres apart indicate connections between those areas.

Conditions on Mars

In the 1970s a fossil river system was discovered in the Gilf Kebir area on satellite images. Many 1000s of years older than the post-glacial settlements described abvoe, it explained many previously puzzling features of the desert landscape including the sands of the Great Sand Sea, the formation of the oases and the shape of some parts of the river Nile. It is now known as the Gilf River System. NASA became interested in the combination of hyper-arid conditions, the relict river system and the varied topography as an analogue for conditions on Mars. Ralph Bagnold’s name comes up again at this point. In 1977 NASA invited him, at the age 0f 81, to address a conference comparing the landscapes of Mars and Earth. As artid and remote as it is, the Gilf still has a role to serve.

Unsupervised tourism

Figure 16. Gilf Kebir tourism was on the rise until the January 2011 revolution, with some highly responsible tours (such as the one in the photo) but there have been a worrying number of irresponsible tourists, unsupervised by qualifed guides.

Even though Michael Asher, who probably ought to have known better, went looking for Zerzura in the 1980s, that legend has probably been put to rest. Unfortunately, the latest visitors to the desert, tourists, are often not interested in harmless exploration. Until the Egyptian revolution, annually over 2000 people were journeying into the Western Desert. Many of the tour companies are highly responsible, with fully trained guides and attendent archaeologists (figure 16). But others are less concerned about the desert heritage and without adequate (or any) supervision some tourists have helped to undermine the formerly pristine archaeological record. Artefacts have been hoovered off the desert floor and into people’s souvenir collections. Rock art has been subjected to brushing with oil or water to bring out the colours for photography and people have been videoed pushing tracing paper onto rock art to trace the art with pencils and pens.

Even though the area has now been declared a national park by the Egyptian government there is still a lot of work required to teach not just the tourists but those responsible for them about how to treat both the portable archaeology and the rock art.

Conclusion

The Gilf Kebir, a vast plateau area scarred with dried river valleys, and surrounded by savannah and Sahel plains with seasonal lakes and pools, was used over a 4000 year period after the last glaciation by hunters and then herders, experts at maximising the exploitation and production potential of environmentally challenging areas. Their lifestyles involved travelling over great distances and trading with a number of different areas. The Gilf Kebir today is arid and inhospitable but its prehistoric remains speak of a time when people lived challenging and vibrant lifestyles in this far-off corner of Egypt.

Image Credits

All photographs copyright Andrea Byrnes, except:

Figure 1 – Public Domain, courtesy of NASA, modified by Andrea Byrnes

Figure 7 – Compilation and titles NASA, Photographs courtesy USGS and USAID. (both US Fed Govt: Public Domain)

Figures 8, 9 and 11 – sketches redrawn from Gehlen 2002 by Andrea Byrnes

Bibliography

All web links checked 2nd April 2012

Asher, M. 1986

A Desert Dies

Penguin Books

Bagnold, R.A. 1935

Libyan Sands: Travel in a Dead World

Michael Haag Ltd

Bagnold, R.A. 1982

Foreword

In El Baz, F. and Maxwell, T.A.

Desert landforms of Southwest Egypt: A basis for comparison with Mars

Washington

Bagnold, R.A. 1990

Sand, Wind and War: Memoirs of a Desert Explorer

The University of Arizona Press

Ball, J. 1927

Problems of the Libyan Desert

Geographical Journal, volume 70

Bierman, J. 2004

The Secret Life of Laszlo Almasy – The Real English Patient

Penguin

Bollig, M. and Bubenzer, O. (eds) 2010

African Landscapes: Interdisciplinary Approaches

Springer

Embabi, N.S. 2004

Geomorphology of Egypt

Cairo

Foder, E. 2005

In Linstadter (ed)

Wadi Bakht

Africa Praehistorica 18 (p.169-211)

Gautier, A. 2002

The Evidence for the Earliest Livestock in North Africa: Or Adventures with Large Bovids, Ovicaprids, Dogs and Pigs

In Hassan, F. Droughts, Food and Culture: Ecological Change and Food Security in Africa’s Later Prehistory

Kluwer Academic, p. 195-208

Gehlen, B., Kindermann, K., Linstädter, J., and Riemer, H. 2002

The Holocene Occupation of the Eastern Sahara: Regional Chronologies and Supra-regional Developments in four Areas of the Absolute Desert

In Tides of the Desert

Africa Praehistorica 14, Heinrich Barth Institut

http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/praehist/seiten/gehlen_etal2002.pdf

Kelly, S. 2002

The Hunt for Zerzura: the Lost Oasis and the Desert War

John Murray

Kropelin, S. 1987

Palaeoclimatic evidence from early-mid Holocene Playas in the Gilf Kebir

Paleoecology of Africa, Vol. 18 (1987), p.189-208

Kropelin, s. 2005

The geomorphological and palaeoclimatic framework of prehistoric occupation in the Wadi Bakht area”

In J. Linstädter, U. Tegtmeier (eds), Wadi Bakht – Landschaftsarchäologie einer Siedlungskammer im Gilf Kebir,

Africa Praehistorica 18 (2005), pp. 51 – 65

http://www.uni-koeln.de/sfb389/sonstiges/kroepelin/249%202005%20AP%2016%20Wadi%20Bakht.pdf

Kuper, R. 1993

Sahel in Egypt: Environmental changes and cultural development in the Abu Ballas area, Libyan Desert.

Krzyżaniak, L., Kobusiewicz, M., and Alexander, J. (eds)

Environmental Change and Human Culture in the Nile Basin and Northern Africa until the Second Millennium BC : 213-223. Poznan

Kuper, R. 1995

Prehistoric Research in the southern Libyan Desert.

Cahier de recherches de l’institut de papyrologie et d’égyptologie de Lille, 17 (1995)

Kuper, R. 2002

Routes and Roots in Egypt’s Western Desert: The Early Holocene Resettlement of the Eastern Sahara.

In, Friedman, R. (ed), Egypt and Nubia: Gifts of the Desert. British Museum Press.

Kuper, R. 2006

An attempt at restructuring the Holocene occupation of the Eastern Sahara

In Koeper, K., Chlondnicki, M., and Kobusiewicz, M.

Archaeology of Early Northeastern Africa

Poznan

Kuper, R. and Kropelin, S. 2006

Climate-Controlled Occupation in the Sahara: Motor of Africa’s Evolution

Science, vol 313, 11th August 2006, p.803-807

Linstädter, J. 2002

Rocky islands between oceans of sand – Archaeology of the Jebel Ouenat / Gilf Kebir region, Eastern Sahara

In Atlas of Cultural and Environmental Change in Arid Africa

Heinrich Barth Institut

http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/praehist/seiten/linstaedter_2007_sfb389_atlas.pdf

Linstädter, J. 2003

Middle and Late Neolithic in the Wadi Bakht region (Gilf Kebir, Egypt)

In Krzyzaniak,L., Kroeper,K. and Kobusiewicz,M.

Cultural Markers in the Later Prehistory of Northeastern Africa and Recent Research

Poznan, p. 129-144

Linstädter, J. (ed) 2005

Wadi Backht – Landschaftsarchaologie einer Siedlungskammer im Gilf Kebir (SW Agypten)

Africa Praehistorica 18.

Linstädter, J. and Kröpelin, S. 2004

Wadi Bakht Revisited: Holocene Climate Change and Prehistoric Occupation in the Gilf Kebir Region of the Eastern Sahara, SW Egypt

Geoarchaeology: An International Journal, Vol. 19, No. 8, 753–778 (2004)

http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/praehist/seiten/linstaedter_kroepelin_2004.pdf

McHugh, W.P. 1975

Some Archaeological results of the Bagnold-Mond expedition to the Gilf Kebir and Gebel Uweinat, Southern Lybian Desert

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol:34 (1975), p.31-62

Riemer, H. 2007

When hunters started herding

In Aridity, Change and Conflict in Africa

Collquium Africanus 2, Heinrich-Barth-Institut

Peters, J. 1988

The palaeoenvironment of the Gilf Kebir- Jebel Uweinat area during the first half of the Holocene: The latest evidence.

Sahara 1: 73-76

Pollath, N. 2009

The prehistoric gamebag: The archaeozoological record from sites in the Western Desert of Egypt

In Riemer, Forster

Desert Animals in the Eastern Sahara

Colloquium Africanum 4, HBI

Sampsell, B.M. 2003

A Traveler’s Guide to the Geology of Egypt

American University in Cairo Press

Schon, W. 1996

Ausgrabungen im Wadi el Akhdar; Gilf Kebir (SW-Ägypten), Teil 1 – 2.,

Africa Praehistorica 8, Heinrich Barth Institut

Shaw, W.B.K. 1936

Rock Paintings in the Libayn Desert

Antiquity 10, 38.

Siliotti, A. 2009

Gilf Kebir National Park

Geodia

By

By