By Kate Phizackerley. Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 5. 3rd April 2012.

With a sister-in-law about to qualify as an NCT adviser (formerly the National Childbirth Trust for those who are not familiar with the organisation), it was perhaps inevitable that at some point I would write about childbirth in ancient Egypt. The specific topic which attracted my attention is the birth bower and its (likely) derivative the mammisi chapel.

The Mundane Birth Bower

The mundane birth bower had a practical role as a place of confinement, common in many cultures, for a mother during delivery of her baby and a purification period post-partum, usually at least two weeks (Westcar Papyrus). At least from the New Kingdom, bowers were a temporary tent-like structure formed of poles used to support mat screens, swathed in vines. It is believed that they were often built on the roofs of houses.

With an ephemeral construction, and sited on the roof of dwellings which themselves do not typically survive, there are no preserved examples. They are depicted on an ostracon from Deir el-Medina among others. A small ground floor room built around a mud-brick platform discovered in many houses at Deir el-Medina is believed to be an alternative form of bower, sometimes called a “birth box”.

Much less is known of birthing practices in the Old and Middle Kingdom periods.

Delivery and Midwifery

Delivery was primitive. Although there are hieroglyphs associated with fertility, such as the symbol for placenta, there is no known word for a midwife. Many commentators draw an inference from this that women lacked skilled midwifery support for childbirth, although recognising that a woman would have birth companions is set out in the Westcar Papyrus (see below). It is possible, however, that too much is read into this. In a society in which women had many pregnancies and had multiple birth companions, it is likely instead that one of the aspects of adult womanhood itself was a knowledge of childbirth and an ability to assist. It is possible that there was no need for a word because it was simply expected that any adult woman, especially one who had experienced childbirth firsthand, could fulfil the role of midwife.

Figure 2 – Kom Kombo relief of woman giving birthThis travel blog photo’s source is TravelPod page: Edfu & Kom Ombo – Day 7

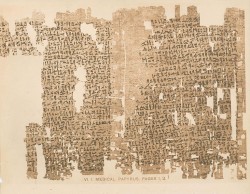

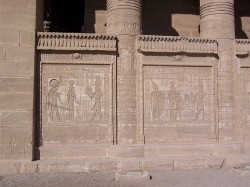

In contrast, wet nurses for royal and noble mothers are well-documented and it seems likely that a nurse would attend an elite birth. A wet nurse would also be employed by poorer families if the mother died in childbirth. Moreover, the Bible (Anon, Exodus Chapter 1) describes the enslaved Hebrews as having midwives and it seems unlikely that the Egyptians had not adopted the practice. Indeed, papyri such as the Ebers Papyrus and the Kahun Papyrus document medical remedies for contracting the uterus and for injuries to the perineum but women also relied on magic and the intercession of goddesses, particularly Aset (Isis), Hathor, Meskhenet and Taweret, for support during labour. Women, probably naked other than a girdle about their hips and with their hair piled upon their heads, gave birth either on their knees or squatting with feet placed on two birthing bricks, as depicted in a relief in the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Medina. The hieroglyph associated with birth also shows a kneeling women with the head and arms of a child appearing beneath her (Robins 1993, p82) and reliefs at Kom Ombo show women giving birth in this position, as well as squatting on a birthing stool (see http://www.flickr.com/photos/jaccodotorg/4168399043/). Many fertility figurines depicting women naked, except for a girdle and with elaborate hair arrangements have been found. (Strumpfel) The Westcar Papyrus describes the confinement and delivery of a woman named Reddjedet, including a description of a birthing stool with a hole in it through which the baby could pass. Five goddesses, Aset (Isis), Nebt-Het (Nephtys), Heqet, Meskhenet and Khnum, disguised as musicians were in attendance, suggesting perhaps that an Egyptian woman giving birth was commonly attended by five or more female companions. The reference to musicians is interesting as the sistrum rattle was generally used in Ancient Egypt to frighten away the God Set and the screens of the vine-swathed birthing bower were thought to have been representative of a marsh. In Egyptian mythology, Isis hid Horus from Set in the papyrus thickets of the marshes of Chemmis. It is therefore possible that the female attendants offered magical protection as well as practical and emotional support to the mother.

Column 3, 25-26 of the Kahun Papyrus also had a recipe for “Preventing acute pains of a woman” … on “the day she gives birth” suggesting that some herbal pain killer was available. The section is incomplete so it is not possible to assess its likely efficacy. Other sections give alternative remedies for pain relief. There are also papyri which include remedies for inducing labour. Unsurprisingly, despite these remedies the mortality rate of both babies and mothers was high.

While it may be thought that women were expected to become pregnant as often as possible, there must have been times when pregnancy was considered undesirable because the Kahun papyrus also has a recipe for preventing pregnancy: a wad of coated crocodile dung was used as a pessary to form a cervical cap.

The Birth Bower in an Amarnan Stellae?

Dorothea Arnold wrote the most comprehensive work about elite women in the Amarna period. She identified (p.98-100) a stela in the Neues Museum in Berlin (Figure 7) which she believes shows King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti in a birth bower. Arnold believes this view is reinforced by a Louvre fragment where a similar scene shows a “zeh netjer” reed structure,which ancient Egyptians would have associated strongly with birthing bowers.

Mammisis

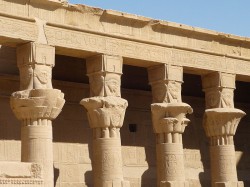

Egyptian birth houses (mammisis) are an important feature of many Late Period and Ptolemaic and Roman temple complexes. Being small temple edifices in their own right, their decoration is dominated by scenes that relate to the nativity and bringing up of the divine child of a local triad.

As the young god was identified with the king, birth houses were also places devoted to the cult of the living ruler. (Kockelmann)

Practical birth bowers should not be confused with these mammisi-chapels. “Mammisi” is a pseudo-Coptic word coined by Jean François Champollion to describe a special exterior chapel, typically aligned perpendicularly to the main temple and surrounded by an ambulatory, although mammisis may be an idealised form of a mundane birthing bower for ritualistic purposes. Described in many texts as peripteral (i.e. surrounded by an ambulatory of even size), Alexander Bedawy takes issue with the term because the front transverse aisle of the Denderah mammisi, for instance, is wider than the lateral or rear aisles, contrasting to the layout of true peripteral chapels in other Egyptian temple contexts. He proceeds to make the case for an architectural symbolism dating back to prehistoric times, such as in the height of screening mats and the use of actual or representational foliage to impart the virtue of a papyrus thicket in screening the birth from the God Set.

If Badawy’s thesis is correct, it seems likely that some of the key symbolism was incorporated into mundane birthing bowers as well. In an article in Edition 4 of Egyptological Magazine, Howard Middleton-Jones considered how the layout of ancient Egyptian temples influenced later Coptic churches and monasteries. There are clear parallels between the birth scenes venerated within mamissis and the Gospel account of the birth of Christ and the role of the Virgin Mary. We might also tentatively track a line of inheritance from the mamissi into the tradition of Lady chapels within many Mediaeval Catholic cathedrals, including the usual position outside the main processional space leading to the holy of holies or high altar.

There is further discussion of the stylistic development of mamissi by Kockelmann (see bibliography).

There are well known examples of mamissis at the temples of Denderah (two), Edfu, Esna (known only from texts) and Philae. The mammisi played host to rituals concerning the marriage of the goddess and the birth of a god and, by Roman times, the later mammisi at Denderah (dating from the reign of Nectanebo I) was used for the enactment of mystery plays concerning the birth of the god Ihy and the pharaoh. (Shaw, p406)

Mammisis are sometimes said to be features only of Ptolemaic and Roman-era temples. While there are certainly many examples from this period, Grimal suggests that the north colonnade on the middle tier of King Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple at Deir el-Bahri “acted as a kind of mammisi” depicting the King’s birth. (Grimal, p211) The New Kingdom Luxor Temple and the Precinct of Mut at Karnak also boast a mammisi (Grimal, pp 266-7, 299), the former depicting the birth of King Amnehotep III.

Ptolemaic and Roman mammisi were dedicated to a god, goddess and the birth of a god as offspring. There is good coverage of the subject, complete with references, at http://www.reshafim.org.il/ad/egypt/institutions/mammisi.htm which reaffirms the view that mammisi hark to the tradition of birthing bowers, saying of the Roman Isis Mammisi at theTemple of Denderah:

“The walls are thought to have had their origin in mats hung up as screens.”

In his treatise on mamissi (see bibliography), Kockelmann goes further:

However, also the cult of the living ruler was “specifically established in the birth houses,” as “the young king was identified with the son of the divine family”; “the aspect of the birth houses as scene of royal cult would explain the remarkable development of these buildings from the 30th Dynasty on” (Arnold 1999: 94 – 95). Moreover, the juvenal god was identified with the rising sun (Daumas 1958: 127); hence, the young king participated in this daily cosmic renewal.

Figure 7 - Berlin Stela which Arnold suggests represents Akhenaten attending Neferttiti in her Birth Bower / Mamissi

If, as Arnold suggests, the Berlin stela of Akhenaten and Nefertiti depicts a birth bower, might the presence of Akhenaten indicate that the birth had special significance and that the structure was not just a birth bower but a mammisi and that the birth depicted was that of a god-heir? In short, is it possible that this suggests, albeit very tentatively, that Nefertiti did indeed give birth to a male heir of Akhenaten, or alternatively that he considered his daughters as heirs even when he may still have had a future son?

Conclusion

Women were full citizens in Ancient Egypt, entitled to own property, manage their affairs and to litigate. Childbirth was a major, and usually recurring, feature of a woman’s life. As in many societies, her ability to bear live children, especially male heirs, was important to both a woman and to her husband. In a highly ritualised society, it is unsurprising that there were strong cultural traditions surrounding childbirth, and that special spaces – birthing bowers – were devoted to the period of confinement.

The generational aspects of the godly Ennead was a foundation of Egyptian religion as Brian Alm has explained in his series on religion here on Egyptological. At some point in the New Kingdom the concept of a special bower or chapel for commemorating these heavenly births came into being, seeing full fruition in the mamissi-chapels of the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

The failure of some commentators to recognise the roots of the mamissi tradition in the New Kingdom may have caused the potential significance of the Amarna stelae, identified by Arnold as birth bower scenes, to be overlooked.

Bibliography

Anon, The Old Testament of the Bible

Arnold – Dorethea, The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt, Metropolitan Museum of Art catalogue, New York 1996 (reviewed by Kate Phizackerley http://bit.ly/HbCi8i )

Badawy – Alexander, The Architectural Symbolism of the Mamissi-Chapels of Egypt, Chronique d’Egypte vol 38, #75, 1963 from http://bit.ly/HG5uZ1

Grimal – Nicolas, A History of Ancient Egypt, first printed 1992, first edition of English translation printed 2003

Kockelmann – Holger, MAMMISI (BIRTH HOUSE), UCLA Encyclopaedia of Egyptology, from http://escholarship.org/uc/item/8xj4k0ww

Middleton-Jones – Howard, Early Coptic Church and Monastic Architecture. The Link with the Pharaonic and Greco-Roman Past. Egyptological Magazine, edition 4 February 2012, /2012/02/early-coptic-church-and-monastic-architecture-the-link-with-the-pharaonic-and-greco-roman-past-7441

Robins – Gay, Women in Ancient Egypt, 1993

Shaw – Ian, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, paperback, new edition 2003

Strumpfel – Jessi, The Images and Power of Motherhood in New Kingdom Egypt, Spring 1999 via http://www.its.caltech.edu/~stumpfel/gallery/arh_120_files/egypt.html

Image Credits

Figure 1 – Sketch from British Museum

Figure 2 – Photogaph used with HTML provided by source site, styled to fit Egyptological

Figures 3, 4,..,7 – From Wikimedia Commons – Public domain or GNU Free Documentation Licence

By

By