By Kate Phizackerley and Michelle Low. Published on Egyptological, Magazine Articles, Edition 6, May 31st 2012

Editorial (Kate Phizackerley)

Was Pharaonic Egypt a nation state? This is not a new question but it is hard to answer for a variety of reasons, including:

- the context of the question is rooted in a modern concept (nation-state);

- Egypt from Dynasty 0 through to the Roman period spans some three millennia; and

- our knowledge remains fragmentary, especially when it comes to abstract concepts like nationality.

To do justice to the question, Michelle Low and I agreed to argue the opposite cases in the Oxbridge and English public school tradition of debate. Michelle’s orginal position was that ancient Egypt was not a nation-state but should instead be characterised as a personal-rule state. Upon discussion, she decided that Egypt probably became a nation-state towards the end of the Dynastic period when the will of Pharoah became somewhat diluted. That left me to argue that Egypt was not a nation state.

To air as many viewpoints as possible we also approached the question of references quite differently. Michelle investigated and quotes many of the writers on ancient Egypt who have published material on such questions. Perhaps because my acaedmic training lies in other fields, I preferred to use the work of political writers.

Which of us is right? It doesn’t really matter. We hope, however, that by adopting this debate-style we have surfaced a wide range of viewpoints and offered some insights for those wishing to consider things like nationality and statehood in greater detail. We would very much welcome anybody wishing to take up the discussion in comments – whichever side you wish to argue!

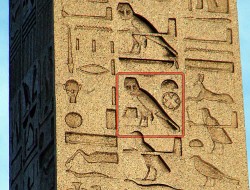

(Image: public domain)

No (Kate Phizackerley)

In answering such a question it appears that one might first ask, “What is a nation state?” Wiktionary pithily states that a nation state is “a political entity (a state) associated with a particular cultural entity (a nation)”. There are many more developed definitions but such elaboration is inapposite. Authors such as Mostafa Rejai and Cynthia H Enlow of Miami University, Ohio and Juan J. Linz, Alfred Stepan and Yogendra Yadav for the United Nations Development Programme contrast nation-states with state-nations. Formal academic definitions are somewhat obtuse and scholars disagree whether some modern “countries” are nation-states or state nations. To attempt to discern such fine nuances in a retrospective study of ancient Egypt seems fanciful.

Egyptian Philosophy?

It is also highly relevant that the question as to whether Egypt was a nation state would likely have baffled the ancient Egyptians themselves, not because they were culturally backward but because the definition of a nation-state is inherently modern and that of a state-nation even more so, with Linz and Stepan claiming to have coined the term in 1996, although there is evidence that the term state-nation was used by Rejai et al. In 1969. Some commentators see the emergence of nation states as a uniquely modern development. Matthew Horsman and Andrew Marshal wrote, “The Renaissance saw the birth of statecraft in its recognisably modern form,” (p4) and also (p5):

It took a popular revolution to create the conditions for the emergence of a distinctly modern nation state in France. The French Revolution of 1789 marked a watershed: in its aftermath the nation was not just the king, his territory and his subjects.

Although it is commonly believed that the Egyptians referred to their land as km.t, Kemet, the Black Land, it is unclear how common was this usage. In his talk to the Bloomsbury Summer School on 12th May 2012 (see Byrnes, Andrea 2012) John Romer was at pains to stress how rarely the term km.t was used. More generally the Egyptians used a town symbol, Gardiner’s O49, to refer generically to habitation. Even the Wikipedia entry for Kemet is in dispute.

When it is unclear whether the Egyptians had a word for Egypt (at least before Ptolemaic terms) and the precise modern definition of nation-state remains subject to debate, at one level it seems inapt, almost pointless, to attempt to discern a precise answer to the question of what defines a nation state and whether in fact ancient Egypt was a nation-state. It may, however, still remain illuminative to consider whether ancient Egypt was both a nation and a state using a simple definition of combination of a polity (state) and nation (a group of people sharing a cultural identity). Our question thus decomposes into two limbs: we first consider whether ancient Egypt was a state and subsequently whether it was also a nation.

Egyptian Polities and Statehood

The question as to whether ancient Egypt was a state is relatively easy to answer at a headline level. There was manifestly a polity which entered into diplomatic relations with its neighbours as exemplified by the correspondence between the Pharaohs Amenhotep III, IV (Akhenaten) and neighbouring leaders, the so-called Amarna letters. There was also a pattern of foreign kings providing their daughters as wives to several Egyptian kings. With minimal ado we can discern an Egyptian state with the King or Pharaoh as the head of state. Less obvious is the date at which such an Egyptian State may be said to have come into existence. (Nor of course was statehood necessarily continuous throughout the entire Dynastic period.) That polities had emerged by Naqada III is not in doubt with Kathryn Bard (p59,60) writing, “The location of this cemetery and the sudden appearance of a new style of ‘royal’ burial at the end of Naqda III, …, all suggest a break with the polity centred at South Town …, probably coinciding with the absorbance of the Naqada polity into a larger one. Such polities were not the land of Egypt as it is now recognised – “Traditionally, the state of Egypt was created when the legendary king Menes led the armies of Upper Egypt to defeat the Kingdom of Lower Egypt…” (Manley).

Traditionally Egypt is considered to be a creation of unification. Nonetheless these pre-unification polities themselves qualify for consideration as both states and nations. The distinction between a polity and a state is complex, perhaps merely semantic. Otto Hintze postulated two dimensions to statehood: a structured system of social classes and military reach, further developed by Theda Skocpol (Mann). There is less evidence of the exercise of military might before the conquest of unification, but again the date for the emergence of a state military is uncertain. Nonetheless, at the point King Scopion (Narmer? – see Lankester) and his successors tried to unify Egypt it is apparent that Upper Egypt possessed both a social hierarchy with the king at its pinnacle and was deploying military might against its neighbours, as for instance illustrated on the Narmer and Scorpion Maceheads (Lankester), although it is uncertain whether unification was achieved militarily (Shaw, p60). Pre-unification Upper Egypt would seem to meet the definition of a state.

Nationhood

The cultural identity of geographical regions had been strong for generations, “… suggests that from the Tasian period onwards, Middle and Upper Egypt from el-Badari to Naqada were increasingly influenced by the culture of the north” (Grimal, p35). The essence of nationhood is however more than shared cultural identity. Nationhood is an embodiment of the sense of “them” and “us”. The evidence for this persists in the designation of Dynastic Kings as the kings of the Two Lands and of the Red and Yellow Crowns. There are strong grounds therefore for believing that Upper Egypt was a nation-state before unification.

Application of our Criteria to Egypt

Egypt was not the first nation state. Upper Egypt possibly was a nation-state, but records are insufficient for certitude, and certainly inadequate to form a view on whether Upper Egypt was the first such state. Certainly any analysis would need to consider other copper age cultures in Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean. But was Egypt itself later a nation state? Linz and colleagues remind that a state can compromise more than one nation:

Given the reality of cultural diversity in many of the polities of the world, the belief that many people have that every state should be a nation and every nation should be a state seems to us to be misguided and indeed dangerous since, as we shall argue, many states in the world today in fact contain more than one nation (or territorially-based cultural groups) within their boundaries.

As previously mentioned, there is evidence that Upper and Lower Egypt persisted as separate nations throughout all or most of the Dynastic period, much as England and Scotland remain separate nations within the United Kingdom. For this reason it is hard to identity Dynastic Egypt as a nation state: it was not a single nation.

Conclusion

The question of whether Egypt was a nation state is of purely academic interest. Whether Egypt fell just within or just without a particular definition of that term has no particular meaning. So far as we are aware it Egyptians did not philosophise about the issue, rendering an assessment even more abstract.

However, if we persist in positing the question, our assessment should be that pre-unification Upper Egypt was a nation state but, as a union of kingdoms, Egypt itself was not one.

Yes (Michelle Low)

With the exception of Antarctica, the world is segregated into countries. However, this was not always the case as prior to the emergence of a state, one’s identity and loyalty was to the family, community and region. With the emergence of ‘nation-states’, a political terrain was founded upon a communal identity among the people, therefore many scholars have insisted that Ancient Egypt, though not the world’s first civilisation, was possibly one of the world’s earliest ‘nation-states’ (Wilkinson, 2010, p.15 & 38; Baines, 2011).

Terminology

But what is a ‘nation-state’ exactly? In this article, we will analyse the characteristics of a ‘nation’, ‘state’ and ‘nation-state’, and review whether Ancient Egypt, from the Pre-Dynastic to New Kingdom period, can be regarded as one of the world’s earliest nation-states as many scholars have speculated.

Nationhood

The ‘nation’ is an occurrence or concept that came to existence in the 16th century and continues to exist, yet it has no apt scientific definition (Anderson, 2006, p.3). Nonetheless, many scholars have attempted to identify this phenomenon. For example in Ishay (1999), the author defines ‘nation’ as a legitimate soul and spiritual dogma founded upon past sacrifices and many more to be made for a better future (p.8), while Bauer in Ishay defined ‘nation’ as a group of people with a common vision bonding to form a society with an identical identity (p.10). Nevertheless, the best and most accepted definition is by Benedict Anderson who stated “an imagined political community – and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign” (2006, p.6). The ‘nation’ is said to be imagined owing to the fact that regardless of the size of the ‘nation’, not all its members have heard of or met one another (Anderson, 2006, p.6). For instance, the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt were known as ‘King of the Two Lands’ indicating that the ‘nation’ was geographically divided into Upper and Lower Egypt, the Red Land and the Black Land. Hence, it is unlikely that all Egyptians had met one another especially since they lacked our modern modes of transportation and technology (Tyldesley, 2009, p.14; Shaw, 2000, p.60-63; British Museum, n.d.). Secondly, the ‘nation’ is imagined to be limited in that no ‘nation’ had/has the notion that the world will one day be theirs (Anderson, 2006, p.7). Generally, a nation’s limit is bounded by its geographical borders, hence for the Ancient Egyptians, when Narmer established the ‘nation’ in Nagada III, its geographical limit extended from the Delta to the Nile’s first cataract (Shaw, 2000, p.63; Wilkinson, 2010, p.33&38). It imagines itself to be sovereign as this idea was created during the Enlightenment era, so if a ‘nation’ had to be under anyone, it would be God (Anderson, 2006, p.7). In the case of Ancient Egypt, it was sovereign in that the people and pharaoh worshipped various gods individually but collectively, as a ‘nation’, they worshipped Amun-Ra (Erman, 1971, p.259-262; Tyldesley, 2009, p.34; Hill, 2010). Lastly, a ‘nation’ is imagined to form a community where equality and a horizontal camaraderie exist although the truth is that there was a social pyramid with the pharaoh at the top and the slaves at the bottom (Anderson, 2006, p.7; Tyldesley, 2009, p.6). Owing to the fact that the community is formed based on shared history, culture, religion, language and political view (Ishay, 1999, p.8&10; Pick, 2011, p.3&5; Habermas, 1998, p.399), there is a horizontal comradeship where each member feels a sense of belonging and desire to perform civic duties as a form of loyalty (Anderson, 2006, p.67; Pick, 2011, p.5). Furthermore, the Egyptians’ strong religious beliefs united them as a community and this abides by the Conservatives belief that religion plays a vital role in unification (Ishay, 1999, p.7). So in terms of a ‘nation’, Ancient Egypt was one.

Statehood

Moving on, a ‘state’ is a defensive politics-based community with an independent leadership that rules justly and enacts laws that must be followed by whomever that is considered part of the ‘nation’ (Pick, 2011, p.3; Gellner, 1983, p.1&4). Shaw (2000) and Tyldesley (2009) noted that during Nagada III, Narmer felt a strong need to unite all of Egypt’s independent cities and form the first largest territorial state, against any external invasion (p.57; p.21). A ‘state’ is sovereign and legitimate only if it is able to enact its legislations and ensure that the ‘nation’ is safe from external threats (Habermas, 1998, p.399-400; Pick, 2011, p.37). In Ancient Egypt, the ‘state’ was led by the pharaoh whose reigning duty was to create and maintain Maat by ensuring the Nile flooded at appropriate times, praying to the gods on the behalf of the ‘nation’, providing them with employment and safeguarding its territory (Baines, 2011; Tyldesley, 2009, p.6). There are seven types of ‘state’ before nation-state: personal rule; theocracy; city state; oligarchy; military state; tribal state, and empire (Pick, 2011, p.3). For this review we will take a look at personal rule state only as it is generally accepted as the first kind of ‘state’ most civilisations adopt. It was almost always a hereditary form of ruling in which religion functioned as a uniting agent and ensured loyalty among members of the ‘nation’ and to the ruler (Pick, 2011, p.3&15). This manner of ruling is evident in Ancient Egypt’s hereditary dynasty and the nation’s religion acting as a unifier (Kreis, 2001.). Therefore, it begs the question of whether Ancient Egypt was a ‘nation-state’ or just one of the world’s most successful personal rule state-based nations.

Egypt as a Nation-State

The basic principle is that there is only one ‘state’ for a ‘nation’ and only one ‘nation’ for a ‘state’ (Pick, 2011, p.5). Therefore when a ‘nation-state’ has been merged for a particular ‘nation’ within its state’s limit, it remains for perpetuity as a constant political entity (Pick, 2011, p.3&5; Gellner, 1983, p.1). In a ‘nation-state’, there is a reversal of roles- the citizens who were once labelled ‘subjects’ are now the ones with power and the ruler’s loyalty and accountability are no longer to himself but to the people who permitted him to govern (Pick, 2011, p.3&37). As stated above, in Ancient Egypt the people were to be loyal to the monarchy- they were the pharaoh’s subjects. Moreover, the people of a ‘nation-state’ were mobile and not puppets the ruler could control. For example, the citizens are free to travel across trading regions while the ruler’s duty was to open borders for them (Pick, 2011, p.10), but this was not the case for Ancient Egypt where the pharaoh decided where he wanted to expand and consequently providing the subjects with jobs (Shaw, 2000, p.73). Furthermore, in a ‘nation-state’ the Church and the administration are separate independent entities (Pick, 2011, p.12) but this was not the case for Ancient Egypt where the pharaoh was regarded as a divine being and a representative of the gods (Tyldesley, 2009, p.18).

Therefore upon further analysis, Ancient Egypt, from the Pre-Dynastic to the New Kingdom period, was inclined towards the personal rule state rather than a ‘nation-state’ as she was governed by hereditary dynasties that utilised religion as a uniting agent. Nonetheless, from the Third Intermediate Period onwards, it appears that Ancient Egypt underwent various political transformations as the Amun priesthood became more influential and eventually ruled side-by-side the pharaoh, and during the Persian period, Ancient Egypt was governed by satraps or better known as viceroys (Tyldesley, 2009, p.174&193), therefore it is possible that a ‘nation-state’ began to emerge during the later periods of Ancient Egypt.

Hence, it is likely that Ancient Egypt is one of the world’s earliest ‘nation-states’ (though date and time are subjective), but she definitely is one of the most successful personal-rule state-based nations.

Bibliography

1) Kate Phizackerley

Bard, Kathryn, Ch4 of The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt edited by Ian Shaw, Oxford University Press, paperback edition 2003, first published (hardback) 2000.

Byrnes, Andrea, Review: Study Day. Ancient Egypt – Myth and History with John Romer, Egyptological Magazine, Edition 6 – May 2012

Grimal, Nicholas, A History of Egypt, 2003 paperback edition, first translated into English by Shaw, Ian 1992, first published 1988.

Horsman, Matthew and Marshall, Andrew, After the Nation State, Harper and Collins, paperback published 1995 (first edition 1994)

Lankester, Francis, Who is King Sorpion?, published in Egyptological Journal, Edition 2, December 2011

Linz, Juan J, Stena, Alfred and Yadav, Yogrendra, “Nation State” or “State Nation”?: Conceptual Reflections and Some Spanish, Belgian and Indian Data, http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2004/papers/HDR2004_Alfred_Stepan.pdf

Manley, Bill, The Penguin Historical Atlas of Egypt, Penguin Books, 1996

Mann, Michael, The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Power and Results

Rejai, Mostaf and Enlow, Cynthia H, Nation-States and State-Nations, International Studies Quarterly, 1969, http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3013942?uid=3738032&uid=2&uid=4&sid=47699012931727

Wiktionary, definition of nation state, http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/nation-state, retrieved 18th May 2012.

2) Michelle Low

Journal Articles

Habermas, J. 1998, ‘The European Nation-State: On the Past and Future of Sovereignty and Citizenship’, Public Culture, Vol.10, Issue.2, pp. 397-416.

Pick, A.C. 2011, ‘The Nation State: An Essay’, pp. 1-93.

Book

Gellner, E 1983, Nations and Nationalism, Cornell University Press, New York.

Ishay, M.R. 1999, ‘Introduction’, in Dahbour, O & Ishay, M.R. (ed.), The Nationalism Reader, Humanity Books, New York, pp. 1-19

Anderson, B. 2006, ‘Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism’ (ed.), Verso, London & New York, pp. 1-7 & 22-36.

Tyldesley, J. 2009, The Pharaohs, BCS Publishing Limited, Oxford.

Shaw, I. 2000, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, London.

Erman, A. 1971, Life in Ancient Egypt, Dover Publications, Toronto.

Wilkinson, T. 2010, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt: The History of a Civilisation from 3000BC to Cleopatra, Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

Websites

Hill, J. 2010, Ancient Egypt Online, http://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/ra.html, Viewed 15 March 2012

British Museum n.d., Geography,

http://www.ancientegypt.co.uk/geography/explore/fea.html, Viewed 15 March 2012

Kreis, S. 2001, Lecture 4: The Akkadians, Egyptians and the Hebrews, http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/lecture4b.html, Viewed 15 March 2012

Baines, J. 2011, The Story of the Nile, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians/nile_01.shtml, Viewed 15 March 2012,

By

By