By Brian Alm. Published on Egyptological, Magazine Edition 10, 16th June 2014

A note of explanation before we begin:

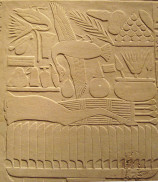

Figure 1. The shape of this libation vessel imbues the offering with the power of its symbols, ankh (life, living) and ka (spiritual essence), reflecting its religious purpose. 1st Dynasty (3100-2900 B.C.).

Admittedly this series will barely scratch the surface of the subject, so I want to call attention to the “Very Good Books” listed at the end, which do a much more thorough job of it than a short series like this can attempt. My essential purpose here is to illuminate the basic themes and images stemming from the ancient Egyptian culture, and to provide a framework for the reader’s continuing curiosity.

Assuming a potential audience ranging from the interested newcomer in Egyptology to the long-studied expert — on an experience scale of, say, 1 to 10 — I am directing this series generally to those in the 1-to-5 group. We will begin with some basic concepts and incrementally build up the background knowledge and recognition of key elements in the ancient Egyptian culture necessary to really see the art and be able to analyze it methodically and with understanding. But not to exclude anyone, I invite those already well grounded in Egyptology to come along with us; perhaps something will spark a memory of a knotty moment in one of your own lectures or discussions that would suggest a comment you could share. But we do have to cover the conceptual basis of the iconography and of the culture as a whole, and I know that all those who have presented Egyptology to the general public will understand that obligation very well.

Despite its impact on artistic expression, I am not covering Amarna — the Akhenaten heresy of the 18th Dynasty — which may dismay some readers, but my purpose is to focus broadly on themes, motifs, symbols and icons that express the ideas of ancient Egypt over the millenia, and not on a brief interlude like Amarna. Fascinating though it is, it is an anomaly in the grand scheme of things, and I prefer to paint with a broader brush for now, and perhaps take up the matter of Amarna sometime in the future. Likewise, to keep this series within practical bounds, I am leaving sculpture, architecture and the Predynastic roots for future discussions.

With those disclaimers, let’s plunge in.1

The Cultural Foundations

Figure 2. A piece of jewelry like this pectoral is literally loaded with meaningful religious and mythological symbolism, much of which would be clear even to an ancient Egyptian who could not read. (We will “read” this pectoral later on in this series.)

Probably only one percent of the ancient Egyptians were literate, and those literate few were royalty, nobility, upper-crust managers and administrators, at least some of the top military people, full-time priests and scribes. But many people could “read” what they were seeing, and understand it without knowing how to read hieroglyphs. The ideas and symbolic iconography were grounded in their culture; the art spoke to them even if their knowledge of the written text was, for the vast majority of the public, rudimentary at best — no doubt limited to a few basic glyphs.

At the population peak — in the Greek (Ptolemaic) Period, 332-30 B.C. — there may have been as many as five million people in Egypt, but from the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 B.C.) through most of the New Kingdom (1550-1069 B.C.2), the population was probably more on the order of three million. So, in these most artistically rich periods, a literacy rate of one percent means that about 30,000 people could read and write.3 The rest did what we are doing now: building a preliterate vocabulary in order to “read like an Egyptian.”

Figure 3. The glyphs “di ankh” instilled life in expressions and objects, making them true and eternal through divine magic. This reads: di ankh mi Ra djet-ta, “given life, like Ra, forever.”

But first, let’s understand the real purpose of the art, why it existed, the context in which it needs to be understood, and the intentional settings in which it is found — tombs, primarily, then temples — but also in the private and personal sphere, if we broaden the definition of “art” to include devotional items such as shrines with “hearing ear” stelae, vessels for libations and offerings, and personal items such as jewelry, pectorals, necklaces, amulets, kohl eye-makeup pots, mirrors, apotropaic knives and other items artfully decorated with meaningful symbols (figures 1 and 2). Whatever the image or object, whatever its magical or mythical roots, whatever the setting or size, the purpose was religious, either directly or by association. “If the ancient Egyptian was aware of ‘art’, it could not have been above the consciousness of his religious experience, and that indeed was wide enough to encompass almost every human activity” (Aldred 1980, p. 11).

The purpose of art was to connect with the divine. A mirror bearing the image of Hathor, goddess of femininity and beauty, was more effective in achieving the desired result with makeup or a hairdo because it could draw upon Hathor’s divine magic. Men worked for weeks or months, sometimes hundreds of feet underground, in the depths of a tomb feebly lit at best, to create splendid, breathtaking murals that covered the walls and ceilings — and then sealed the tomb and left; their work was never intended to be seen again by mortals. The art was meant for immortals: the Justified who had entered Eternity and the deities in whose society they now lived.

The temples were open, true, but not public, open only to some, and most of the art likewise had religious purpose, expressed one way or another. Even the self-promotional art of the most boastful pharaohs — Ramesses II, the prime example — emphasized their faithfulness to their ordained duty: dominion and cosmic order. Battle scenes, expeditions to the land of Punt, fishing and hunting scenes — all attested to that religious sine qua non: maintaining the primacy of the First Land, divinely chosen to rise from the primordial nothingness, and in so doing, ensure the order of the universe. “The Egyptians believed that works of art and architecture were essential to the smooth functioning of … the world itself…. The mere expression of an idea by artistic means made it efficacious and capable of functioning in its own right…. The arts were able to convey in visual form abstract concepts underlying the king’s role in society and his relationship to the gods.” (Malek 2003, pp. 4-5). And again: the purpose of art was “to represent, influence and manipulate the real world … Egyptian art was concerned above all with ensuring the continuity of the universe” (Shaw/Nicholson 2008, p. 41).

Figure 4. Tombs were equipped with real food and drink, but also food and drink made of clay, wood or stone made “real” by magic

Art historians speculate expertly about what is meant in Western art, and can illuminate the works with explanations that are completely plausible, but their thoughts are still subject to challenge by other art historians who offer likewise plausible interpretations. But Egyptian art, with very few exceptions, spells it out precisely in icons and symbols. However, to unlock the meanings it is necessary to know the cultural, conceptual basis of it all. If we want to read like an Egyptian we need to understand the religion, mythology, iconography and symbolism expressed in art. And we have to be prepared for some peculiarities, and not only read like an Egyptian, but think like one, too.

To write something, or to picture something, was an act of creation that gave life to whatever was written or pictured, and made it true and permanent. A written expression or graphic image stamped di ankh is “given life” (figure 3). That ubiquitous message, di ankh, is a good place to begin our illiterate, or at least semi-literate quest for certainty; it explains volumes about ancient Egypt. Something that never happened could be written, and once stamped “di ankh,” became fact.4 Words, statues and objects blessed by the words di ankh became true and eternal through divine magic. The tombs were equipped with real food and drink, but also food and drink made of clay, wood or stone (figure 4). The words alone would do, in fact.

Di ankh combines two very important glyphs: di (given), the stylized loaf of bread (represented as a lambda-like inverted V), which we see often in offering presentations, and ankh (life, living), which — interestingly enough — is also the word for mirror: you see your own living image in it5 (figure 5). The boy pharaoh Tutankhamun (Tut-ankh-amun) was “the living image of Amun.” Ankh-ib was a close friend: one who lives in the heart (ib).

It is important to bear in mind that the Egyptians were fixated on life, not death — death was a portal to the continuation of life — and they used the same word for both the present life and the Afterlife: ankh. Often di ankh appears as part of the expression di ankh mi Ra djet-ta (given life, like Ra, forever) (figure 3) written on a wall or obelisk in adoration of a king. We must understand that it is much more than adoration: it is a blessing that has been made permanent fact by the invocation di ankh — a blessing with potency. Writing was of higher order than speaking; it made things true and durable. Words were “of god”; the Egyptian term for what the Greeks called hieroglyphs was medu-netjer, “the words of god.”

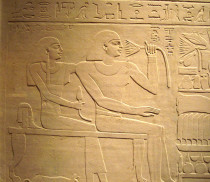

Figure 6. The artist-craftsman’s duty was to make permanent, living expressions of traditional themes, such as the man-and-wife relationship, protection and eternal life. Even their dog, sleeping at their feet, goes with this couple into Eternity.

The word for sculptor or carver, s ankh, means “he who makes it living.” That is a key concept in understanding the purpose and place of Egyptian art, as well as the role of the artist and even the canons that ruled the production of art going back well into Predynastic times. There are no famous ancient Egyptian artists. Very few ever signed their work. Art was not for art’s sake; nor was it there to record history. It existed to create reality and capture that reality permanently.

The purpose of art was not to beautify a wall or demonstrate the artist’s talent, much less his innovation. Therefore the artist did not stretch his mind to seek creative new themes, styles and techniques, but focused on the traditional themes that emerged from mythology and the theology that informed it.6 Artists, in fact, were not called artists, but simply craftsmen. Their patron deity was Ptah, god of craftsmanship, and also the god of ethical order and truth, who spoke “true of voice” (maa kheru). That was what was being tested in the Hall of Two Truths at the time of Judgment; when the deceased had passed the dual tests of the Negative Confession and the Weighing of the Soul, Thoth recorded that he had spoken “true of voice” and was now “Justified,” a sanctified soul. Artists, in league with Ptah as craftsmen dedicated to truth, were obligated to make the message a living expression of traditional themes, not a personal performance. Therefore, while the religion itself was not dogmatic, there certainly was a dogmatic canon of art. Art was founded on a religious base, and “severe deviation from the norm might have endangered [its] potency and efficacy” (Malek 2003, pp. 7-8). To keep themselves focused on their obligation, artists recited magical formulae as they worked, just as other craftsmen did (figure 6).

Artistic Method and the Canons of Egyptian Art

Figure 7. All these feet are right feet: the most telling feature of a foot is the arch, and therefore conveys the idea “foot.” The Egyptian artist’s purpose was to convey the key information about something, not to picture it with photographic accuracy.

Even children recognize the oddity of human figures in Egyptian art, and contort themselves to “walk like an Egyptian,” but try as they might, they cannot quite manage to get their torsos and just one of their eyes twisted around to appear frontally while keeping their legs and faces in profile — not to mention presenting two left feet when walking to the right, or two right feet walking left. So why did the Egyptian artists do it that way?

It is because the Egyptian artist’s goal was to convey as much information about things as possible, and simultaneously, instead of trying to replicate reality with three-dimensional perspective. He didn’t try to make it “look like” reality, but focused on the ideas to be conveyed. The arch is the most telling feature of a foot and therefore conveys the key fact about the idea “foot.” So it doesn’t matter whether it’s the left or right foot — every foot must express that key information, the arch (figure 7). Likewise the contorted “Egyptian look” — the body is arranged to present the information thought to be important about it.

Figure 8. The Egyptian artist presented both frontal and aerial views of Nebamun’s garden pond simultaneously in order to provide all the information at once. Western art would turn it into a trapezoid, to show perspective — how it seems, not how it is.

If a box is square, we would try to show its three dimensions by turning it into a trapezoid, foreshortened to show depth. The Egyptian artist would say it is not a trapezoid, so don’t make it look like one: it’s a square, so show it square. If there are things in the box we need to see, the Egyptian artist would show those things above the box so the viewer could see it all at once and without distortion. If an artist today painted a picture of Nebamun’s garden pond, it would be trapezoidal, to show depth from our perspective, as viewers; for us, how it seems to be trumps how it is. The 18th Dynasty Egyptian artist who painted figure 8 instead presented both frontal and aerial views simultaneously in order to provide all the information at once. Things farther away look smaller, yes, but the Egyptian artist knew they weren’t, so he painted them higher, not smaller; to show perspective he stacked objects horizontally.

What we call reality, the Egyptian artist would call distorted and incomplete information. Egyptian art was conceptual, focused on the information to be conveyed about the subject. Our art is perceptual — it looks at the subject from the perspective of the observer and tries to create the illusion of three dimensions. (Brewer/Teeter 2007, pp. 194-204).

Once past that mental hurdle, the canons of Egyptian art are pretty straightforward. Status and role were expressed by artistic conventions such as size, color, pose and placement. Dominant figures (gods first, pharaohs next, and then anyone in authority over others) are larger; high officials and generals tower over their subordinates, male heads of household are bigger than their wives (figure 9). Men are shown ruddy red and women pale: men work outside and women inside. (It doesn’t matter if it’s false: the idea of gender roles was the information the Egyptian artist wanted to convey, whether the idea reflected reality or not.) A man’s wife always has her arm around her husband’s shoulder or waist, or is touching him in a scene of frozen repose (figure 6). Men and gods extend the left foot forward, active and assertive, while women keep their feet dutifully together. Children are shown holding one finger to their mouth (figure 9). Women in mourning have their arms raised, throwing dust over their heads. Serving girls are passing out hors d’oeuvres and scented ointment cones to guests at a dinner party and performers are singing, playing and dancing (never mind that it’s all in a tomb) (figure 10). Men in spotless white linen plow their fields, enjoying work in the Afterlife without sunburn, biting flies or sore muscles (figure 11). Pharaohs beat the brains out of their inferior foes. Each scene is conveying information, delivering a message.

Figure 10. Life goes on: performers sing, play and dance, celebrating the continuation of life in a tomb

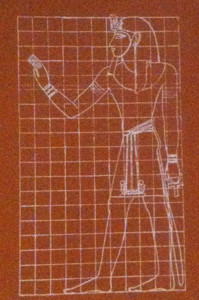

How did they manage to keep the look of the human (or divine) figure so consistently uniform? —the grid system (figure 12). A wall to be painted was first coated with plaster and gesso, if necessary, and then a grid of eighteen squares was snapped on it with a string dipped in red ink, or drawn with a straightedge. Each square was about equal to the width of a closed fist. Parts of the body were measured in multiples of the grid square: the knee at the sixth square up, the bottom of the hip at the ninth, the neck at the sixteenth. The eighteenth was the hairline, not the top of the head, to allow for headdresses and crowns. A fourteen-grid system was used for sitting figures. This system was in place by the 5th Dynasty (24th century B.C.) and it remained standard until the late Third Intermediate Period (1069-664); then the proportions changed to a 21-square grid, which made the royal figures taller and thinner.

Figure 11. Men in spotless white linen enjoy work in the Afterlife without sunburn, biting flies or sore muscles. The story continues in stacked registers.

When the grid was done, a draftsman made a sketch in red ink, after which a master draftsman made corrections in black. The process was so well organized that several men could work on the same scene, doing different parts of the work at once. It was like an assembly line; even the process itself reflected Egypt’s obsession with consistency, control, stability and order. (See Robins 2008, p. 107, and Brewer-Teeter 2007, pp. 199-201 for more on that.) They applied the paint with brushes made from frayed papyrus stalks or sticks, or tufts of hair.

Figure 12. By means of the grid system, the uniformity of bodily proportions remained consistent in art from the 5th Dynasty on.

For relief sculptures, it was largely a matter of lighting and surface material. Inside tombs, raised relief was used; the walls were usually prepared with a layer of plaster, about an inch thick, so it was easy to sculpt, or, more laboriously, the background stone was chiseled out. Raised relief captured the available light from torches made of twisted fiber, candles or small oil lamps. The incised method, sunk relief, was typically used on external surfaces, to make the best use of sunlight and shadow (figures 13 and 14).

For color, they used mineral pigments, which were more durable and less apt to fade over time: gypsum, calcium carbonate or quartz dust for white; carbon soot, lamp black or coal for black; yellow ochre-iron oxide for yellow; red ochre-iron oxide or hematite for red; malachite or a mixture of copper carbonate and yellow ochre for green; lapis lazuli for dark blue; turquoise for light blue; and a synthetic mix of copper-calcium-tetrasilicate for the ultramarine “Egyptian blue.” (See Aldred 1980, p. 30, and other books listed below for more on technique.) For binding, they may have used egg tempera or a water-soluble gum — opinions differ — but whatever it was, it worked very well.

Their work is astonishing not only for its extraordinary quality but also its longevity.

Now, thousands of years later, in some places the colors are still there; Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple, Djeser-djeseru at Deir el-Bahari (figure 7), is a good example.

Figure 13. Raised relief like this one of Montuemhat, a high official of the Late Period, c.670-650 B.C., was typically used inside tombs, in order to capture the available light.

The men who created these works of art, eons ago, are still speaking to us across the gulf of time. What are they saying? In Part 2 we will get into the meanings imbedded in Egyptian art so we can begin reading those ancient messages.

Footnotes and References

1 The author’s 2011-2012 series, Ancient Egyptian Religion, provides additional depth for an understanding of the Egyptian culture. See http://egyptological.com/2011/06/30/ancient-egyptian-religion-part-1-3920 for the first part (seven parts, July 2011–July 2012); Part 6 focuses particularly on art.

2 New findings by Nadine Moeller and Robert Ritner at the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, suggest strongly that the New Kingdom/18th Dynasty started about 1600, 50 years earlier than traditionally believed, based on textual references to a volcanic eruption in the Aegean Sea that appears to be the event that created the island of Santorini (Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Spring 2014). Compelling though their evidence is, I am following the Ian Shaw Oxford chronology for the time being.

3 Some have estimated as many as three percent, but that seems high, and may include barely literate scribes who were actually copyists, responding to the increased market for copies of the Book of the Dead, driven by increasing population and greater affluence.

4 Egyptian words are italicized to distinguish them from their Greek or English equivalents, but pharaohs’ and deities’ names are not.

5 See Barbara O’Neill’s superb article on mirrors, Reflections of Eternity – An Overview on Egyptian Mirrors from Prehistory to the New Kingdom, http://egyptological.com/2011/06/30/reflections-of-eternity-3869, June 2011.

6 Note that while the themes and purposes remained standard, there were subtle changes in portrayal — particularly in sculpture — that suggest contemporary attitudes toward kingship, sovreignty or religion, as well as some new techniques of execution. See Cyril Aldred’s Egyptian Art, 1980, for full details.

Figure 14. Incised, or sunk, relief was typically used on external surfaces, to make the best use of sunlight and shadow, as on this wall at the Temple of Amun (Karnak).

Photo Credits

Figure 8 by Andrea Byrnes (from the tomb of Nebamun, British Museum)

All other photos by Brian Alm. Figure 12 is from the Putnam Museum, Davenport, Iowa. Figure 13 is from the Brooklyn Museum, New York. Figures 3, 7 and 14 are from Egypt. All other figures are from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA), New York.

A Very Short List of Very Good Books

Aldred, Cyril. 1980, Egyptian Art, Thames & Hudson, London, U.K.

Brewer, Douglas, and Emily Teeter. 2007, Egypt and the Egyptians, Cambridge U.P., Cambridge, U.K.

Clayton, Peter. 2006, Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames & Hudson, London, U.K.

Dodson, Aidan; Salima Ikram. 2008, The Tomb in Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, London

Hagen, Rose-Marie and Rainer. 2002, Egypt: People, Gods, Pharaohs, Taschen, Köln, Germany

Malek, Jaromir. 2003, Egypt: 4,000 Years of Art, Phaidon, London and New York

Robins, Gay. 2008, Art of Ancient Egypt, Harvard U.P., Cambridge, U.S.

Robins, Gay. 2001, Egyptian Statues, Shire, Princes Risborough, U.K.

Schulz, Regina, Matthias Seidel. 2007, Egypt: The World of the Pharaohs, H. F. Ullmann, Königswinter, Germany

Shaw, Ian; Paul Nicholson. 2008, Illustrated Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, American University in Cairo Press

Teeter, Emily. 2011, Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge U.P., Cambridge, U.K.

Wilkinson, Richard. 1992, Reading Egyptian Art, Thames & Hudson, New York, U.S.

By

By