By Barbara O’Neill. Published on Egyptological, Magazine, August 14th 2012.

In the Beginning

Before I begin this article recounting my experiences on an Egyptian excavation, I have to point out that protocol dictates that I cannot be specific about the project I worked on. That is only right and proper. When the majority of Egypt’s archaeological record remains unreported and unpublished it would be wrong of me, a novice in the business, to give details of the mission before dig leaders have had an opportunity to report officially to the SCA (the Supreme Council of Antiquities, the body which oversees all archaeological activity within Egypt). Therefore, this account will of necessity lack specific detail, although I hope that the following will provide a reasonable overview of an ‘awesome’ experience (in the true sense of this word); one which will remain with me forever.

Time, real and suspended

Apologies if the following observations appear rather ad hoc, but as anyone who has spent time getting up close and personal with the ancient past will confirm, it takes an inordinate amount of time for normal function to resume back in the real world. If you are ever fortunate enough to find yourself part of an excavation team in Egypt, you will find that ‘time’, as most of us understand that concept, changes radically. It starts with one’s working day. The morning alarm was set firmly for 3.30 am. This allowed enough time to wake up, shower and breakfast before heading out for the dig bus, literally at the crack of dawn. It sounds dire but one finds oneself in a different space with another mindset on a dig. Amongst the dig novices, all housed under the same roof in West Bank Luxor, no one ever looked sleepy or unprepared for the day ahead. No one ever complained about an ungodly hour. It was heavenly to rise with the Egyptian sun; blissful to experience the deliciously cool temperature of a Luxor morning. What might elsewhere be viewed as unacceptable timings were easily assimilated as one gradually left all normal activity behind and began following the ‘other worldly’ timetable of an excavation. By 5am, sunrise is well underway in Luxor. The hot air balloons were just reaching cruise height at that hour, keeping pace with the sun as both hovered over the supra-green fields of the West Bank (figure 1).

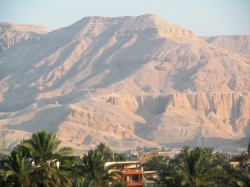

A short journey through sleepy villages brought us to the base of the Theban plateau, the location of many dozens of tombs dotted across the limestone hills. As for suspended time, the concepts of’ now’ and ‘then’ quickly become blurred when one’s working space is a two thousand year old tomb and where one habitually breakfasts in the shadow of the über impressive Deir el Bahri plateau (figure 2).

From modern Luxor to ancient Thebes

It was more than twenty years since I last visited Luxor, but little had changed. There were more motorbikes and fewer donkey carts perhaps, but unlike other parts of the Arab world where the transatlantic dress code of jeans, t-shirts and a minimalistic dress sense has swamped traditional culture, the people of modern day Luxor looked exactly the same as I remembered them back then. Without exception (excluding Westerners) every woman was covered, usually in regulation black, elegantly and effortlessly graceful as they went about their business; always looking cool despite the searing heat of an Egyptian summer. Men are more likely to appear in western clothes but fewer have abandoned the gallibaya than I expected (figure 3).

Meanwhile, the shops along our daily route to the dig site differed from each other only in their signage. Most contain more or less the same range of products-bakery, grocer, greengrocer, electrician squeezed in alongside male dominated coffee shops, the pharmacy, the shoe shop, a laundry and the tailor. Local beauty salons, which often seemed to double up as the wedding-dress makers were all busy in the weeks leading up to Ramadan. Many weddings take place at this time of year, leading into the holy fasting month. It is an auspicious time and these particular salons/dressmakers were constantly busy, jubilant ullulation confirmed this at dusk, as that day’s entourage of brides departed.

Occasionally spotted on the west bank, though more frequently seen on the East bank, western style eateries, restaurants and a rare Internet café or two stand out, not least due to their garish signs. The West Bank streets are rough on walkers and not much better for other forms of transportation, challenging the most agile pedestrian. Forget disabled access or even keeping your feet dry; the daily practice of hosing down dusty earthen pavements outside shops and houses makes mud, and the closely associated muddy puddle, a constant. It is fairly certain that the ubiquitous inappropriately dressed tourists (usually young, western and sad to report, female) one spots within temple complexes on the East Bank would surely not continue upright for long, teetering down West Bank streets oblivious to sense and sensibilities. European Health and Safety Inspectors would find themselves with ‘flagged urgent’ issues to discuss, let loose at these same locations (figure 4).

Surreal is so real

Surreal sensations can never be commonplace but do seem to become the norm as one functions amidst the trappings of the ancient past while coping with the realities of the present. I have long been fascinated by ancient Egyptian concepts of time; one of many Egyptian dualities where time is eternal perfection or ‘Dt’, most often associated with Osiris and the flawlessness of creation. At the same instant, time can be cyclically repetitive or ‘nHH’, most often linked to the sun god Ra and recurring cycles of life. One might experience aspects of both Dt and nHH time as they occur simultaneously on an Egyptian dig. The realities of the repetition experienced during the all-important mission work of registering a multitude of limestone and other objects could indeed become repetitive, but it was never ordinary. The juxtaposition of using 21st technology in ancient tombs never failed to produce wry smiles; we used laptops, high-end digital cameras, even mobile phone technology while working deep underground, seemingly far from the real world where such technology is commonplace.

Registration work often plunged one into an almost out of body experience as one delved into the dog-eared site copy of Allen, flicking through formulaic Middle Egyptian phraseology in a valiant attempt to decipher partially destroyed hieroglyphs, before carefully writing a 21st century AD date on limestone fragments from a similar year BC. Another hour or two might be taken up manning the excavation of a new trench; watching as structures unseen for thousands of years were once again revealed in the light of a 2012 summer morning. Later, one might have the opportunity to observe skilled conservators as they worked on fragmented limestone using state-of-the-art preservatives created through space age technology. Surreal becomes real when one finds oneself labelling an assortment of ancient items which might include faience beads, inscribed papyrus or scraps of mummy wrappings, packing these carefully into Sainsbury’s and Wal-Mart sandwich bags, everyday receptacles as far removed from their contents in style, form and function as it is possible to be. I’m ever-hopeful that one day someone will ask me ‘what’s the weirdest thing you’ve ever popped into a plastic sandwich bag’? I have my answer ready, ‘the tip of a mummified finger with traces of gold leaf still visible on the fingernail’!

Local and Ancient

Characters abound on an established excavation site. The reis, or dig foreman, stands proud and tall commanding all aspects of the physical space. He must be commanding and most definitely able to assume the position of ‘he who will be obeyed’. Ours had many years of experience working for the top people on the best sites. Yet for all that, there was a definite softness in his personal interactions with the youngest workers; a sense of humour at our clumsy efforts to navigate the site, not a practice for the faint-hearted. When physical features of an excavation site are referred to as ‘the bridge of doom’ and ‘the hole to nowhere’, you already have a red flagged ‘note-to-self’ to stay alert at all times.

Novices and students are usually outnumbered by the ‘bucket boys’, hard working men who move effortlessly from trench to tomb, across impossibly death-defying rickety ladder bridges and up the steepest inclines for hour after hour through the hottest time of day, at the hottest time of year with never a sign of fatigue. Swinging their rubble laden baskets up from trench to shoulders effortlessly, they form a graceful ballet choreographed from a starting point in the tomb below, straight up to the growing mounds of detritus on high where they build mini-Theban hills of ‘left-overs’ surrounding the site. This slow moving band of brothers casts long shadows along the upper ridges of the excavation site from dawn to midday with the sun at its highest point, before heading home to rest. Located in the shade of the biggest mound sits the oldest ‘bucket boy’, a semi-retired elder who spends his days sifting through the heap of his more active companions’ discarded rubble. Eagle eyed, though no longer lithe enough to work the trenches himself, his job is to pick out the smallest scraps that may have escaped first examination in the cluttered trench. Petrie might look on approvingly from this old excavator’s mound, nodding in sage approval at his efforts and at the efforts of the experienced excavation team, assessing, recording and measuring the complex stratigraphy of each well-worked trench (figure 5).

Layers of Life

To the novice excavator, what initially looks like a rough wall of mud dotted with stones, straw and rubble soon takes on a more complex meaning; irregular layers indicating multiple usage of a particular space. In an archaeological trench time is marked in layers; layers packed with tomb remnants, settlement deposits and flood debris, no neatly defined distinctions here. If one is lucky, traces of ancient rooms, porticos and stairs might be indicated in these spaces, but even the remnants of much-later-than-the-tomb though still ancient stables are of interest to modern archaeologists. Assessing what gradually emerges from multiple trenches was a vital part of our day, as was recording levels with theodolite and measuring equipment as the dig progressed, always deeper and increasingly wider. Novice excavators are left in no doubt of the importance of this careful recording of trench layers, taking care to plot accurate graphs indicating recognisable remnants of ancient occupation. Within one trench one might find the outlines of long eroded domestic settlement or inscribed papyrus fragments suggesting the location of a room from a long destroyed Coptic monastery or reworked stone from a much later mosque. It is no small thought, the dawning realisation that the space within one excavation trench may have been sacred to people from at least three distinct cultural traditions; ancient Egyptian, Coptic and Arab. Thebes encompasses rich remnants from all of these with a good sprinkling of Greek and Roman thrown in for good measure. One never forgets the fact that equidistant, ever-present and beneath everything lies an Egyptian tomb complex, for it was her first and oldest tradition which dominated the entire ‘world’ of Egypt and the Egyptians when this particular Theban ground was originally dedicated as a burial site.

It’s all Relative

‘Time is relative’ and that cliché takes on a whole new meaning when you are stopped short, hardly daring to breathe upon finding an ancient thumb print casually pressed into the base of a faience shabti, indicating where an ancient craftsmen had finished off his work. I pressed my own thumb print against his, still clearly visible on the base of just one of the many hundreds of little worker statues this craftsman would have produced over the course of a day. The fact that his day (to say nothing of his thumb) existed thousands of years before mine; that sensation of shared humanity never grew old and remains with me now, freshly poignant as all precious memories are.

In Thebes (for it is impossible when away from village and town where the silent hills dominated everything to think of this place as modern day Luxor) any understanding of time is relative, suspended and surreal. Perhaps it was always thus? The ancients may be long gone, with mere traces of their craftsmanship and their beliefs remaining, inscribed into chunks of broken stone and delineated across crumbling tomb walls. It is nonetheless important to preserve what is left and to witness, as I have, how painstakingly this preservation is being carried out, with every scrap of stone, painted plaster and fragment of papyrus logged, tagged and squared away, carefully preserved and recorded because each piece is essential. I understand that now. The next trench could answer important questions or pose new ones; the past is important and Egypt’s past is important to us all (Figure 6).

Ancient Memories

Egypt herself has been described as the world’s largest open air museum. If so, then Thebes is most definitely a beautifully carved doorway into this superlative repository. The ancients may be long gone but Thebes endures in Dt perfection and nHH eternity; so too my memories of a summer never to be repeated and always treasured – have I mentioned it already? I’ve worked on an Egyptian archaeological mission, right there in the foothills of ancient Thebes.

Image Credits: Barbara O’Neill

By

By