By Garry Beuk. Published on Egyptological, Magazine. August 14th 2012

Introduction

In Part 1, we discovered how Arthur Mace took excellent advantage of a distinguished family name, overcoming the fact that wealth would not play a part in making his dreams a reality. Through education, an apprenticeship with his distinguished relative Flinders Petrie and a devotion to proper artifact conservation, Mace ensured respect from his peers. In Part 2, I will show how Mace continued to make contributions to Egyptology throughout a prolonged illness. His conservation techniques preserved artifacts spanning the Metropolitan Museum in New York to the pyramids in Lisht. Mace’s final acts of preservation, as he worked in the tomb of a previously unknown pharaoh made a name for him, although it may very well may have also contributed to his untimely passing.

1912 – 1914 – A Return to Egypt

Mace returned to field work during the seasons of 1912 to 1914. He travelled to Lisht to excavate once more for the Metropolitan Museum. The first season was taken up with plans and notes on the pyramid cemetery of Amenemhat and he also began writing his publication on Senebtisi. Mace spent the following seasons excavating the south east corner of the pyramid and searching for and attempting to excavate tombs of officials.

Flood-water once again hampered his progress; Mace had come to Lisht prepared with an eight horse power boiler and a two inch pulsometer run by a mechanic from Cairo. But even with the addition of a second boiler borrowed from the Public Works Department the machinery could not keep up with the flow of water into the tombs, causing Mace to express that on excavations “life was finely balanced between a state of hope and disappointment.”

The season was also marked with a personal highlight, the birth of Arthur and Winifred’s first child, Margaret Ellen on February 22nd 1913. Arthur and Winifred also had a second daughter, Anne on November 8th 1915. Born with Down’s syndrome, little is recorded about her. She appears in occasional photographs with Margaret but available letters do little to shed light on the details of her life.

1914 – 1920 – War and back to the Metropolitan

The start of World War 1 in August, 1914 put a temporary halt to further excavations. Mace signed up to be a special constable and was determined to enlist, which he did in the summer of 1915. This was somewhat unexpected because at the age of forty he was too old to join the Army, but by claiming to be only 39 he was able to enlist. He joined the 2nd Battalion, the 28th London Territorial Regiment and was quickly promoted to the rank of Sergeant. His hope was to be stationed in Egypt, but suffering from bronchitis and malaria he was transferred to the Army Service Corps in England and then Italy.

The war brought ample time for Mace to work on his forth coming publication, The Tomb of Senebtisi at Lisht, which he coauthored with Herbert Winlock. Publication was completed in 1916 and rave reviews would follow, including those of James Breasted (figure 1) from the University of Chicago who praised the scientific methods not only of the excavation but of how it was reported. The significance of this can be seen when one considers that 96 years later it is still regarded as an essential reference to Middle Kingdom burial study.

Mace’s health continued to deteriorate as 1918 brought about the end of the war. He left active duty exhausted, ill and in no way able to withstand the rigours of field work. Recognizing this, Albert Lythgoe insisted that Mace return to the Metropolitan Museum. It was at this time that Mace completed some of his most impressive acts of artifact conservation. He worked on restoring a pair of jeweled toiletry caskets discovered by Petrie in the Lahun cemetery of Senwosret II.

The caskets, found in the grave goods, included with the Twelth Dynasty burial of Senruset II’s (figure 2) daughter Sit-hathor-yunet, had been reduced to thousands of fragments of ebony and gold. First, meticulously sorting them by size and shape, Mace glued them together utilizing an existing box in the Louvre as reference. The finished product is an amazingly beautiful representation of ancient art. Arthur was a perfectionist and modestly stated that the work was “frankly conjectural”, as the true imagery of the caskets was not known. Lythgoe, however, was delighted with the results and after Maces death stated that it was “one of the most elaborately painstaking and accurate pieces of archaeological reconstruction within my knowledge.”

In 1920 Mace would venture on a new path, that of lecturing. He delivered a well researched presentation on Egyptian poetry. He concluded that ancient poets depended upon rhythm rather than rhyme. He introduced the hypothesis that Akhenaten’s legendary hymns to the Aten influenced later Hebrew writings, relating its striking similarities to Psalm 104. Mace also demonstrated how Egyptian folktales were the first to use popular themes later showing up in tales such as that of Ali Baba.

1920 – 1921 – Lisht

Mace’s health slowly improved to a level adequate for him to return to Lisht, for the first time since the outbreak of war. His excavation focused on the clearance of the western side of the pyramid. But by November, Mace was again bedridden with fever and he remained incapacitated throughout the remainder of the month. Being away from Winifred and their children and routinely ill, Mace found a much needed second family amongst the villagers of Lisht. These unique relationships helped him to overcome the loneliness that remote excavations can often bring.

The seasons of 1920-1921 brought about a number of discoveries, among them a foundation deposit in the south west corner containing an ox skull, broken pottery and most importantly six clay bricks. The significance of the bricks was that they were inscribed with the name of Amenemhat I,(figure 3) putting to rest any uncertainty as to whom the pyramid had been originally constructed for.

1922- 1923 – A life changing opportunity

Antiquities laws were coming under fire in 1922. The prevailing thought was that Egypt was not retaining enough of its artifacts and as a result the rules on concessions for foreign excavators were to be changed. This meant that a division of discovered objects would no longer favor the excavator as it had in the past. This had been especially beneficial in encouraging both wealthy patrons and museums to dig in Egypt and had often been used as a bargaining chip by directors of the Antiquities service to retain funding for expensive digs.

With the concessions rewritten and funding slim, Lythgoe changed his initial plans and decided to delay Mace’s work at Lisht until the end of the season and have him work with Winlock in Thebes. These plans would never come to be, as Mace’s future would be drastically altered by the discovery of a previously obscure pharaoh’s tomb, that of Tutankhamen, (figure 4) by Howard Carter. The discovery would pull the soft spoken Mace into the public limelight and prove to be both a blessing and a curse. Politics would mix with archaeology creating a public relations nightmare that would forever change the face of archaeology.

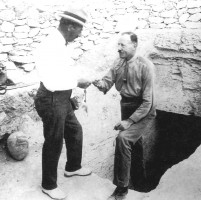

Mace had once quipped to Howard Carter, after Carter’s fourth unsuccessful season with Carnarvon, that “Archaeology is like a second marriage – the triumph of hope over experience” (Meyerson, 2009). In this, their sixth season, Carter and Carnarvon (figure 5) found that very triumph with the sensational discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb on November 04, 1922. The ensuing excavation brought about Carter’s request to the Metropolitan for the services of photographer Harry Burton. Lythgoe, sensing that cooperation with the excavation might prove beneficial to the fledgling Department of Egyptian Art, quickly agreed to lend Burton to the team. In addition, he offered the services of Mace stating, “I know of no-one without exception, to compare with him in the patient and painstaking skill necessary for the preservation of evidence and fragile material such as you have…” (Lee, 1992) Already thought by his peers to be a genius in conservation, Mace was added to the team and arrived in Luxor on Christmas Eve 1922.

Mace and Carter were acquainted with each other, sharing a bond of having both worked with Petrie. They also embraced a common philosophy on the importance of detail throughout the course of an excavation. Mace was put in charge of the restoration of the fragile items as they were brought from the tomb. First, surface dust was removed, measurements made, notes written and copies of inscriptions put on filing cards. Then, conservation measures were performed and finally the object was photographed with detailed notes made of the specific conservation technique utilized.

The importance of the work that Mace performed on the artifacts cannot be overstated. Carter estimated that without on site conservation, less than one tenth of the artifacts would have survived the trip to Cairo. Mace’s meticulous efforts resulted in less than .025% of the artifacts being lost (Tyldesley, 2012), an amazing accomplishment when compared to other excavations of his day where the standards were far less, resulting in losses much greater. Mace proved to be innovative in his efforts, one example being his attempt to save a fragile linen pall. The pall, made of fabric with hundreds of gilded bronze flowers adorning it hung above the second shrine, and was tearing under its own weight. Mace and Carter had to crawl along planks placed on the first shrine and carefully cut the flowers off to reduce the weight. They then wound the pall on a giant wooden roller that Mace had constructed specifically for this purpose. Unfortunately, these efforts were wasted as the pall, left in the conservation tomb, was deteriorated beyond salvaging when Carter and Mace were later locked out of the tomb by the Antiquities Service.

The preservation of artifacts in itself is not glamorous work. It is slow and fastidious, requiring an inordinate amount of patience if the process is to be done correctly. An example of this is when Mace worked on a delicate wooden box (catalogue #21) inscribed with Tutankhamen’s cartouche, that he first strengthened with melted paraffin wax. The contents of this single box took him three weeks to sort through. Bead garments, sandals and gloves were crammed into the box, further increasing the difficulty of identifying and conserving the individual pieces. The box did yield clues to the king’s life, in the form of gloves that Mace estimated would fit a child of three to four years of age. Based on this and the large amount of child’s clothing and furniture found, Mace was the first to speculate in a newspaper article in 1923 that Tutankhamen may have come to the throne as a child.

Mace and Carter worked well together, perhaps to be attributed to the fact that they were polar opposites. Mace was well educated and highly regarded by his peers. Having nothing to prove he often appears in photographs in casual attire, looking relaxed and confident. Carter, on the other hand was certainly not born into prosperity, he had little education save for his experience with Petrie. He was known to be disagreeable over the minutest of issues, and almost always appears in photographs uncomfortably “posed”, dressed in formal clothing including a top hat and bow tie, (figure 6) as if trying to overcome the fact that he was not regarded a gentleman by the highly structured Edwardian Social class system.

Whether because or in spite of their differences, Carter showed an unusual ability to work collaboratively with Mace. As early as April 1923 Carter had proposed to include Mace in the publishing and lectures that would follow the clearance of the tomb. Mace and Carter worked all day excavating the tomb and their nights were filled with writing what would become the first of three popular volumes of the discovery. Mace has been given little credit for his participation. Some modern reprints of the volume omit his name completely, though manuscripts found by his daughter years later prove that he was the major force behind the actual writing. A letter to his wife Winifred testifies to this fact; “I’ve done the first chapter and most of the second, and today he (Carter) was dictating to me his actual account of the discovery of the tomb.” (Mace, 1923)

As time went on, distractions would become inevitable and Mace would be called upon to assist with damage control, particularly pertaining to the exclusive reporting deal Carnarvon had contracted with The Times. Under the controversial agreement, The Times was given exclusive rights to be the first to publish news of the discovery. This essentially prevented all other newspapers from being able to report finds in a timely manner as they had to obtain the rights from The Times. Further, this incensed the Egyptian press, as they were cut out of pertinent facts from a discovery made in their own country. With a growing sense of nationalism, and a distrust of foreign powers, Egypt was becoming a powder keg ready to explode and this did nothing to calm the distractions created for the excavating team. In a letter to Winifred, Mace relays the difficulties created by these events when he writes ‘Archaeology plus journalism is bad enough, but when you add politics it becomes a little too much.’(Reeves, 1990)

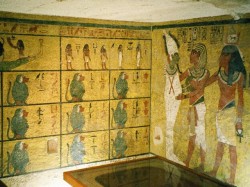

On February 16th 1923 Mace assisted Carter in taking down the sealed door to the burial chamber. Mace expresses that he was “knocked… all of a heap, I think it’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen anywhere” (Reeves, 1990) at the sight of the shrines, specifically the shrine containing the canopic jars and the four free standing statues of goddesses on each side (figure 7).

The stress of the opening of the burial chamber, perceived government interference, the press and visitors from every walk of life demanding tours proved to be a bit much for the excavation team and a decision was made to take a week’s holiday. Mace went to Aswan with Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn. He seemed to form a bond with both of them that had previously not existed. In a letter to Winifred, Mace gives a rare personal view on the Earl when he states “Carnarvon’s a queer fish, but in spite of his oddities very lovable.”(Lee, 1992) Less than a month later Carnarvon died of an infection and Mace took over total control of the excavation. Carter assisted with funeral preparations at Carnarvon’s residence, Highclere Castle, (figure 8) for over a month. His absence did not slow down progress, Mace had a history of planning and running excavations and the transition was easily made. When Carter returned he was impressed with the work that Mace had done, writing to Winifred, Carter states that Arthur’s advice behind him and fighting instincts had helped him (Carter) through (Lee, 1992).

1923-1924 – Bad Politics

The second season of 1923-1924 shook the archaeological world. Personally, the season started tragically for Mace when his eldest daughter Margaret had an appendicitis followed by a nearly fatal affliction from typhoid. Margaret barely survived and Winifred brought her to Egypt in December to be with Arthur and to aid her recovery in the dry Egyptian climate. The arrival of his wife and daughter helped to rejuvenate the spirits of Mace, whom depended heavily upon the support and advice of Winifred.

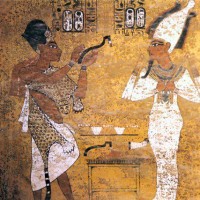

Mace was now prepared to start what he anticipated would be an extremely productive and busy season. Utilizing evidence from paintings on the tomb wall depicting Ay, Tutankhamen’s servant and successor performing the opening of the mouth ceremony, (figure 9). Mace is quite possibly the first to speculate that Tutankhamen died of unnatural causes. He proposes this theory in 1923 when he states ‘It was Eye (Ay), moreover who arranged his (Tutankhamen’s) funeral ceremonies, and it may even be that he arranged his death, judging that the time was ripe for him to assume the reins of government himself.” (Tyldesley, 2012) This type of speculative reporting was uncommon for Mace, a man who required complete study and documentation prior to the publishing of any scientific facts, but it is very likely that it helped to propel the first volume on the discovery that he and Carter had written to the position of a number one best seller in Paris.

The season was marked with discord, the excavation hampered by what Carter felt was severe government interference in the clearance of the tomb. The antiquities department was closely watching his every move and without the guiding hand of Carnarvon to smooth the process over it became an increasingly volatile situation. Constant visitors, (figure 10) ranging from foreign dignitaries to government VIP’s demanding private tours continued to weigh heavy on the excavators time. These interruptions created constant threats to the proper and timely preservation of artifacts that was necessary to ensure their well being. Winifred sets the tone for just how embattled things had become when she writes in December 1923 that “work has been so delayed and there are so many troubles, Mr. Carter might even close the work down, then who knows what will happen….”(Reeves, 1990)

Throughout this turmoil Mace continued, performing exceptional work when conserving the chariots and magnificent black wood and gilded plaster life size statues of the king. He also accompanied Carter and Lythgoe to Cairo in an attempt to work out differences with the Minister whom had issued a controversial directive that prohibited the wives of the excavators from being present at the planned raising of Tutankhamen’s sarcophagus lid. Carter viewed this order as a direct insult to his collaborators and their wives. As Winifred had feared, Carter threatened to abandon the excavation mid season and to secure the resignation of both Mace and Burton. A compromise was eventually agreed upon and the lid was successfully raised without the wives in attendance on February 12th 1924. Mace spoke of the day being filled with mixed emotions and stated that; “the dream of every Egyptologist has been spoilt by jealousy.” (Lee, 1992)

The final insult came shortly after the lid was raised and it proved to be too much for Carter to take. A letter arrived from the Minister that effectively cancelled the compromise previously made in Cairo. The wives had not only been prevented from attending the official raising of the lid, but were now prohibited from entering the tomb altogether. Carter, along with Mace and Burton, immediately posted an official notice resigning their positions.

Mace assisted Carter in preparing statements for attorneys in a suit filed against the government while still encouraging Carter to seek peace through diplomacy. He was also with Carter when Pierre Lacau, the Director of the Department of Antiquities, came to Carter’s residence to demand he turn over the keys to the iron gates locking the tomb (figure 11). Lacau came to realize that Carter and Mace, as well as the rest of the excavation team were essential in completing the delicate removal and preservation of the artifacts. Albert Lythgoe later stated that the government probably did not take over the tomb because when they arrived to inventory it, they were so impressed with Mace’s notes and methods and did not feel they had a suitable individual to take over.

But for now the team was devastated and all hope seemed to be lost as evidenced by Mace’s statement to his mother in law that “the fates seem against us don’t they”? (Lee, 1992) Carter locked himself in his house refusing to meet with anyone other than Mace.

1924-1927 – Leaving Egypt

It is difficult to ascertain with complete certainty the degree to which the stress of this situation impacted Mace, as well as the rest of the excavation team. Mace’s health began to deteriorate again; he became thin, ill and bedridden under the stress and finally left Egypt for home in March 1924. On their return trip the family stopped in Italy hoping that being in this beloved country would distract Mace from the Tutankhamen affair and improve his health. Unfortunately, this desired effect did not occur and Mace became more ill preventing the family from returning home from Italy when planned.

Between the years of 1924 to 1927 Mace became a shadow of the man he once was. He reportedly suffered from arsenic poisoning and lacked the strength to even prepare notes on the Lisht Pyramid for publication. It is unknown how Mace fell victim to arsenic poisoning, if this is indeed what he was suffering from. Arsenic was widely used not only as a medicine but also by taxidermists and museums, so exposure to it certainly could have occurred. Mace himself later attributed his illness to swallowing too much sand and dust while digging in Egypt. He continued to travel, seeking an elusive reprise from his illness in England, the Riviera, Switzerland and New York.

In autumn of 1927 Mace was placed in the care of a nursing home and remained there until his death on April 6th, 1928. Winifred remained by his side saying that his passing was typical of Mace. After a final illness lasting ten days he “just lay back, no fuss” (Lee, 1992). Winifred, distraught over Arthur’s death refused to ever speak of her time in Egypt. His notes, letters and diaries were banished to a box in the attic.

His daughter, Margaret, sought to follow in her father’s footsteps, securing an interview for the Egyptology program at Oxford University. She was told during this interview that Egyptology was not a proper career for a woman and regrettably dismissed. Arthur’s legacy seemed destined to die, until a quiet spring day in 1989 when Margaret would once again discover the box containing his story, a story she was determined to share with the world.

Conclusion

Throughout his career Mace certainly found “the groove” his mother had mentioned earlier in his life. Not only had he set up the entire Egyptian department at the Metropolitan Museum, he also wrote the Middle Kingdom section of the departments handbook.

Unfortunately, Mace did not publish a great deal before his untimely death; the sole large scale publication he completed was on Senebtisi. His belief that the publication of findings should not be done until the excavation was complete ran contrary to the approach of many Egyptologists of his day including his mentor Petrie. Although these principles were admirable, they also left much of his excavated work inaccessible to other researchers and contributed to his lack of scholarly recognition outside of his participation in Tutankhamen’s excavation.

Mace’s daughter Margaret shared a fear common to the Ancient Egyptians, that with the passing of time her father’s name had been forgotten. It is up to those of us who appreciate the lore of history and the individuals who wrote it, to ensure that her fear never becomes a reality.

Bibliography

Hoving,T., 1978, Tutankhamun, The Untold Story, Simon and Schuster

Lee, C., 1992, …the grand piano came by camel, Mainstream Publishing Co. LTD

Mace, A., 1899-1900, Abydos Diary

Meyerson, D., 2009, In the Valley of the Kings, Ballantine Books

Reeves, N., 1990, The Complete Tutankhamun, Thames and Hudson.

Reeves, N. and Taylor, J., 1992, Howard Carter Before Tutankhamun, Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Romer, J., 2003, Valley of the Kings, Castle Books.

Tyldesley, J., 2012, Tutankhamen, Basic Books

Image Credits

Figure 1, James Breasted, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years

Figure 2, Pyramid of Senruset II, Public Domain

Figure 3, Pyramid entrance of Amenemhet I, Unrestricted free copyright use allowed

Figure 4, KV62, Creative Commons Generic License 1.0

Figure 5, Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years

Figure 6, Howard Carter, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years

Figure 7, Canopic Shrine, Creative Commons Generic License 2.5

Figure 8, Highclere Castle, Creative Commons Generic License 2.0

Figure 9, Ay in The Opening of the Mouth Ceremony KV62, Public Domain

Figure 10, Queen Marie of Romania, Public Domain, Life of the author plus 70 years

Figure 11, The entrance to Tutankhamun, Life of the author plus 70 years

By

By