By Andrea Byrnes. Published on Egyptological, Magazine, 14th August 2012

Introduction

To call William Hesketh Lever an entrepreneur or a visionary would be to pin him down, to imply a limit to the scope and depth both of his personality and his achievements. Lever was both these things, but he was so much else besides. He was a philanthropist, an innovator, a skilful salesman, a marketing genius, a reluctant politician, even on occasion an inventor. He was also a supporter of the rights of women, factory workers and the elderly, an enthusiastic ballroom dancer, an eccentric, a fanatic, occasionally a tyrant, and always a family man. His energy, enthusiasm and his ability to produce ideas and turn them into successful enterprises were remarkable His astonishing contributions to social progress in England are spectacularly praiseworthy, and he was knighted for them. In spite of one or two grim mistakes his intentions were always good. Amongst his various extra-curricular obsessions, which included architecture, ferns and gymnastics, the 1st Viscount Leverhulme was a dedicated collector.

Lever (figure 1) was born in 1851 into a Middle Class area of Bolton, an industrial town in northwest England, with loving parents and eight siblings. The young William Lever owed his launch into commercial life to the successful wholesale grocery business, established by Stones and Hesketh and his father James, who had been taken on as a partner of the company. Starting in the warehouse with a broom, he quickly rose through the ranks, redesigning the company’s accounting system and becoming one of the company’s best and most obsessive salesmen. His successes were rewarded with a partnership in the business, and at the age of 33, already a reasonably wealthy man, he declared himself ready to retire. But retirement was just a euphemism for a new venture – soap. The production, distribution and marketing of Sunlight and other soaps made Lever his millions and allowed him to indulge himself, his family and his ever-expanding work-force.

The Lady Lever Art Gallery and the Egyptian Collection

One of Lever’s biographers, Adam MacQueen, says that Lever wondered to whom all this income really belonged. He concluded that a share of it was owed to his workers. To that end plans were draw up for the construction of a perfect village in which his factory workers could live, and work began in 1899. Like Deir el-Medineh, Port Sunlight was built next to the place of work, the soap factory. Unlike Deir el-Medineh it is today, as it was then, a medley of different architectural styles set in a green and airy landscape with wide avenues divided by swathes of green grass, flower beds and trees. All houses had front and back gardens and a minimum of two bedrooms. Cricket lawns, bowling greens, tennis courts, a theatre, an open air swimming pool (heated with surplus heat from the soap factory), a cottage hospital, a personal fire brigade, and various improving societies and clubs were all provided. To top it off, a library was built with a small display area to show off a changing selection of his ever-expanding collection of antiques and antiquities.

Lever himself owned four vast homes and by 1913 he had filled them all to capacity with his collections of antiques, 18th century furniture, paintings, sculptures, Chinese porcelain, Wedgwood china and assorted antiquities. His strategy was to buy only really good pieces, but his taste was eclectic and the mix of styles and periods is remarkable.

The Lady Lever Art Gallery was not part of Lever’s original vision for the village but having filled his homes to capacity and finding the display areas of Port Sunlight’s library and other public buildings insufficient, he decided to build a gallery so that he could properly share his collections with the general public. He was the first British industrialist to create a gallery for his personal collections, although it was a practice very much in vogue in America, where he had visited with his wife and son. Described by MacQueen as “the purpose-built Portland stone wedding-cake” (2004, p.197) the art gallery was named in the memory of his wife Elizabeth, his childhood sweetheart, who he referred to as “my better three-quarters” (figure 2). Work began on the museum in 1914, with George V in attendance, and was opened in 1922 by Queen Victoria’s youngest daughter Princess Beatrice. The items on display were selected by Lever personally and included new works purchased specially to cater for broader tastes than his own.

Lever seems to have shared a general interest in ancient Egypt that was permeating the northwest at that time. He had clearly been aware of Egypt as a boy of 13, when he remarked in a letter sent whilst on holiday in the Isle of Man that “On Friday we had a sail on a steamer and though that it would be very nice sailing to Egypt if there were not such a thing as sea-sickness!” As an adult he never visited Egypt himself, but he sponsored some of John Garstang’s excavations in Abydos and Meroe between 1906 and 1913. In return he received finds from the digs, a perfectly legitimate practice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and one of the principal ways in which early Egyptologists financed their work in Egypt.

John Garstang (1876-1956) was an obvious choice for Lever (figure 3). Twenty six years Lever’s junior, he went to school in Lever’s native Blackburn before going to the University of Oxford. After graduating he excavated in Britain and the Levant as well as in Egypt and the Sudan. He carried out his first Egyptian fieldwork with William Flinders Petrie when he was 23. He became a lecturer in Egyptian Archaeology at the University of Liverpool in 1902 before becoming Professor of Archaeology at the University of Liverpool in 1907, a position he held until 1941, and was on the committee of the Institute of Archaeology’s museum. He worked at Hierakonpolis, Abydos, Beni Hasan and Esna in Egypt, as well as Meroe in the Sudan. The University of Liverpool’s online history of the Garstang Museum provides a helpful insight into Garstang’s role in distributing objects to other museums:

Institute staff, usually Garstang, would also receive a proportion of the material sent back to Liverpool which they might dispose of as they saw fit. Garstang, for example, was generous in dispersing his finds among different museums and collectors in the United Kingdom and overseas as well as advertising in the likes of The Times for applications to receive objects.

The Access SSN curatorial website has the following to say on the subject of the Lady Lever collection:

The Lady Lever Art Gallery is also part of National Museums Liverpool and contains a collection of over 300 Egyptian objects collected by Lord Lever (1851-1925). These are largely from the excavations of John Garstang at Abydos and Meroe, many of which are on long-term loan to Bolton Museum and Art Gallery.

The items that are on display at the Lady Lever are a far from coherent collection, and although the museum provided labels for some, if not all, there were no specific provenances shown and no acquisition numbers given. I am guessing that they must have come from the Abydos excavation, rather than from Meroe. Sadly, most of the Egyptian items in the Lady Lever, forming part of a display in a small gallery dedicated to Lord Leverhulme and his various activities, are in a very dimly lit room on a shelf at the bottom of a cabinet displaying numerous other unrelated objects. Consigned to gloom, they are quite difficult to see and were a nightmare to photograph – the dubious results shown in the article are thanks entirely to the ISO speeds possible with my digital camera and the assistance of Photoshop (figure 4). The other three items are in a well lit room full of Greek vases. It’s a shame that they cannot all be reunited in the light.

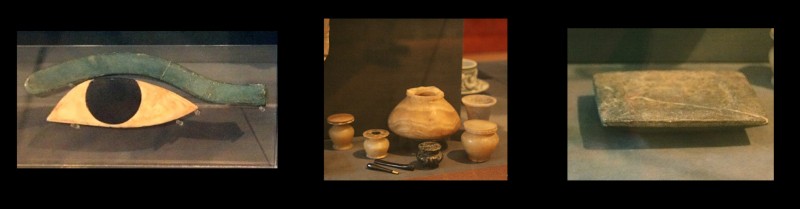

The items in the Lever gallery (with no provenance or acquisition numbers shown on the labels), are as follows (figures 4 to 6), with the information shown derived from the labels in the cabinet:

- Figure 5.1 – A pair of inlaid eyes and eyebrows, alabaster, obsidian and blue faience, Dynasty XII

- Figure 5.2 – Kohl pots, diorite and alabaster, Dynasty XII-XIII

- Figure 5.2 – Kohl sticks, haematite, Dynasty XII-XIII

- Figure 5.2 – A jar, alabaster, Dynasty XVII – XVIII

- Figure 5.3 – A palette, serpentine, Dynasty XII-XIII

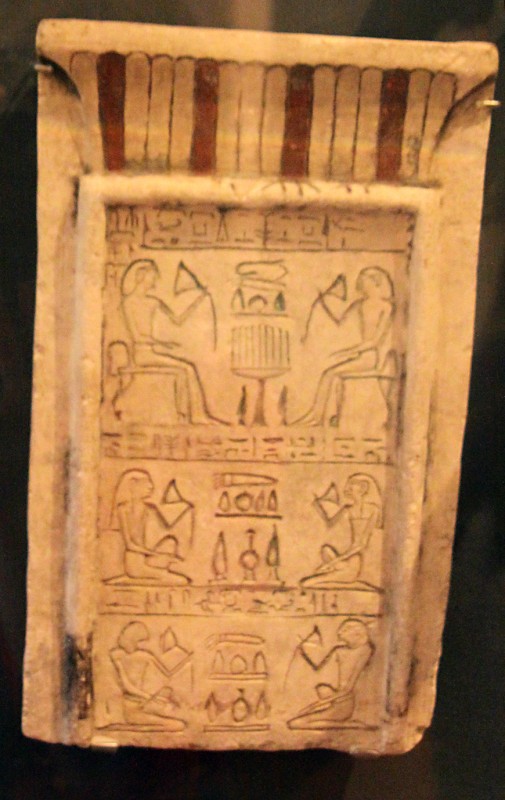

- Figure 6 – A stela, limestone, Dynasty XIII

The palette is a small rectangular one, made of a greenish stone identified as serpentine. It stands next to the kohl jars, and together they may have formed a discrete group of cosmetic items.

Next to the palette is a pair of very fine sculpted faience eyes and eyebrows, the eyes made of white alabaster with black inlays of (the label states) obsidian. The eyebrows are a shade of greenish blue.

The five kohl jars are just a few inches tall, the smallest example, made of diorite, no more than an inch or so tall, the rest made of alabaster. Four are finely worked, with squat rounded bodies, defined bases, short necks and wide flat rims. Two have lids. The fifth jar is less finely crafted, more vase than jar, with a wide open mouth. All are dated to Dynasties XII-XIII. In amongst them a taller jar has been placed, dating to the New Kingdom (Dynasties XVII – DVIII), with a wide elegantly shaped body of banded alabaster, a short straight neck and only the hint of a rim. Sitting next to the jars are two haematite kohl sticks.

Hanging over the jars and palette is a tiny stela, no more than 10 or 12 inches tall (figure 6). The poor lighting and resulting poor photographs make it difficult to make out the hieroglyphs, but the top line has a clearly inscribed opening to the offering formula. Rather crudely done, but nicely framed, the three registers show the owner of the stela sitting in a chair opposite a lady who is presumably his wife, an offering table between them. This is echoed in the two lower registers: in the middle register two women kneel opposite each other with a table between them, each holding a lotus flower; beneath them two male figures kneel in the same way, also holding lotus flowers. They are probably the couple’s children. The offering table between the seated figures in the top register is by far the most elaborate. Above the registers, some of the original red paint survives in the frieze beneath which the rest of the stela sits. Although rather crudely crafted, it has a lot of charm to it and would be worth investigating further.

In the other gallery, dominated by Greek vases, there were two canopic jars, unlabelled (figure 7), and a purple porphyry mortar (figure 8). The canopic jars are an attractive pair, with carved lids representing two of the four brothers of Horus – the baboon-headed Hapi and the human-headed Imsety. Both are rather fine items made in a beautiful banded stone, probably alabaster. There were no labels accompanying them and it would require a little research to find out their provenance and to discover what happened to their companions, perhaps allocated to another museum or collection.

Next to the jars is a very fine Roman purple porphyry mortar, minus pestle (figure 8). Purple porphyry (porfido rosso antico) is unique to Egypt’s Eastern Desert and was much-admired by the Romans who quarried it and exported it in large quantities from Mons Porphyrites to Rome and beyond, to be featured conspicuously in various temples and public buildings. The label that accompanies it suggests that it may have been collected originally by Thomas Hope in Italy. Thomas Hope (1769-1831) was a notable connoisseur who formed a considerable collection, most of which was sold after his death.

Without knowing the provenance of any of the items it is impossible to comment on them as a group, even if they formed one.

A 17th Century Puzzle

Standing at the doorway to the Lever gallery with its tiny collection of Egyptian objects, a 17th Century A.D. bust of a young girl sits on a column (figure 9). It is a typical piece of its time and place. On closer inspection, however, the column turns out to be purple porphyry.

As stated above, purple porphyry is found exclusively in Egypt’s Eastern Desert, and was mined only very rarely after the Roman period, most notably in the Victorian era, when a small number of items were commissioned. There’s no mention of the column on the label, but it seems highly unlikely that the sculptor of the bust would have had access to the raw material.

It is possible, although highly speculative and impossible to verify, that whilst the bust is undoubtedly 17th century, the column may well be Roman. Perhaps it was a souvenir from a Grand Tour, when European aristocracy shipped Roman objects back to their homes by the crate. It sets off the white marble sculpture beautifully.

Egyptian Influences

Beyond the two galleries containing Egyptian items there are various items in the collection that show how Egypt’s motifs gripped the imagination of various very different types of people, who expressed their admiration in highly distinctive ways.

By far the oldest of these is a Roman cinerarium (figure 10). Sitting in a room full of statues from different periods, some of them frankly grotesque, it is an elaborate little piece, broadly rectangular in form with a Latin inscription facing out, which states that it was originally made to hold the ashes of Caius Perperna Geminus, who died at the age of sixty-eight. According to the Liverpool Museums website it was commissioned by his heirs Caius Perperna Agathopus, Saturnina and Fortunata, a freedman and two freedwomen. However, it was heavily “restored” in 18th century Italy, when it was provided with heavy ornamentation including a lid with two rather nice winged sphinxes, neatly carved so that they rest along the main line of the stone block, facing outwards towards the onlooker.

Winged sphinxes were also a theme to emerge in one of the Wedgwood rooms. Three very finely crafted examples were on display, one of which is shown here (figure 11.1), the attention to detail and the precision are remarkable, the colours soft and gentle, sitting on bases of blue jasper. The highly stylized effect would have been at home in any contemporary drawing room. Other Wedgwood items also adopted and then adapted other Egyptian motifs. A very fine red ware dish features a number of different images lifted from ancient Egypt that would undoubtedly have puzzled the Egyptians who would neither have juxtaposed these particular motifs in this particular way, nor would have given them such a fashionable, and somewhat santized make-over (figure 11.2). Another Egyptianized item in the red ware collection is a squat rounded jar hosting the same motifs, but with the addition of a rather lovely crocodile knob on its lid (figure 11.3).

Moving into the Empire gallery, where a replica Napoleonic bedroom has been built, a pair of Egyptian-themed candlesticks in black and gold stand, unlabeled, next to Napoleon’s death mask (figure 12). At quite the opposite end of the taste scale from the Wedgwood items, the black candle sticks depict curvaceous slender young women wearing Egyptian-style head-dresses, golden candle-holders on their heads. They are a typically romanticized celebration of Egypt’s art following Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt and the resulting publication of Napoleon Bonaparte’s Description de l’Egypte published between 1809 and 1822 and Vivant-Denon’s earlier Voyage dans la basse et la haute Egypte published in 1802.

The two styles, Wedgwood’s formal classicism and the Empire’s romanticism, couldn’t have been more different ways of interpreting Egypt’s art.

In a rather different direction, a final and lavish work with an Egyptian theme is the riotously elaborate 1821 “Triumph of Cleopatra” (otherwise known as “Cleopatra’s Arrival in Cilicia”) by William Etty, who was a very successful artist and was considerably admired by Lever (figure 13). The artist, whose fame was secured by this painting in contemporary London, was clearly interested less by Egyptian art than the possibilities of the story and the joy of filling the chaotic boat with bodies in various states of undress. There isn’t a sphinx in sight, and the painting is remarkably short on Egyptianized themes. The buildings are Classical in style and where clothing is depicted, most of it is inspired by Greek and Roman designs. The only concession to Egypt’s Pharaonic heritage is the winged sun disk that adorns Cleopatra’s canopy. The painting is all about the action in the moment, the vortex of figures swirling around Cleopatra who, unlike everyone around her, remains serene in her golden boat, one breast revealed, with putti, most surprisingly and amusingly, overhead.

Conclusions

When he died in 1926, a substantial proportion of Lever’s collections were sold off at auction, but the items in the Lady Lever represent the best of his years of collecting and when the remainder of items at his home in Thornton Hough were sold off in 2000 on the death of the 3rd Viscount, a staggering £9 million was raised. Both his private and personal collections are testimonies to Lever’s skill in purchasing antiques and antiquities.

The museum was handed to the nation in 1986. Very little about it has changed. After the handover, the repair of the ornamental fountain in front of the museum cost Unilever Merseyside Ltd (who owned the fountain) some £30,000, and the museum itself has now been expanded into the subterranean areas with a new gift shop selling books, cards and up-market souvenirs, a smart cafe/restaurant selling hot and cold meals (with photographs of Lord Leverhulme’s Thornton Hough home on its walls), and an activity area for children. There is also a new display dedicated to Lord Lever himself in room 26.

If you are interested only in the Egyptian objects, then the Lady Lever Art Gallery would not be worth a separate trip. There are only a handful on display, with the remainder on loan to Bolton Museums. If, however, your interests are as eclectic as Lever’s himself, then the Lady Lever is a splendid art gallery and museum, well worth a detour from either Chester or Liverpool. Port Sunlight village, such an unlikely oasis in the part of the Wirral that has become industrial and urban sprawl, is most certainly worth a visit in its own right. The display of Lord Lever’s Egyptian collection may be on the seriously modest side, consisting of just a few items, but it forms part of a much larger story of industrialist contributions to Egyptology in the northwest of England, one that would have been much appreciated by contemporary Egyptologists like John Garstang.

Image Credits

Figure 2. The Lady Lever Gallery – Port Sunlight on geograph.org.uk (http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/943102) by Dave Green. Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike license 2.0.

Figure 3. John Garstang in July 1956. This work was released into the public domain by its author, Jhajdu at the wikipedia project. This applies worldwide.

All other photographs taken at the Lady Lever Art Gallery and Bolton Museum by Andrea Byrnes.

References

Books and papers

Hochschild, A. and Marchal, J. 2008 Lord Leverhulme’s Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo, Verso Books

Robinson, L. 2006, William Etty: The Life and Art. McFarland and Co.

MacQueen, A. 2004. The King of Sunlight. How William Lever Cleaned Up the World. Corgi.

Websites

Access SNN (curators’ group in the UK for curators who are responsible for archaeological collections from ancient Egypt and Sudan)

http://ssndevelopment.org/acces_ssndevelopment/home/acces/public_html/

The Palestine Exploration Fund – Professor John Garstang

http://www.pef.org.uk/profiles/professor-john-garstang-1876-1956

Liverpool Museum and Art Galleries – History of the Lady Lever

http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ladylever/history/

Liverpool Museums and Art Galleries – The Lady Lever Art Gallery – Collection

http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ladylever/collections/

University of Liverpool – History of the Garstang Museum of Archaeology

http://www.liv.ac.uk/sace/garstang-museum/museumhistory.htm

Other

The Lord Leverhulme displays in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, Wirral, Merseyside (Liverpool Museums and Art Galleries)

By

By