By Howard Middleton-Jones. Published on Egyptological, Magazine, August 14th 2012

Introduction – The Risk to Heritage

Figure 1 The Qubbat el-Hawa site from across the Nile at Elephantine, showing the Tombs of the Nobles and remains of the Coptic Church. (Howard Middleton-Jones 2010)

In previous editions of Egyptological a number of themes have been discussed relating to the Coptic (Early Christian) Period of Egypt, and as such the reader will have now appreciated the complex issues and challenges facing the Coptic people of Egypt, both past and present.

As we have witnessed recently, a new period in the history of Egypt has arrived, that of the first Egyptian President elected by popular mandate. However, this is just the beginning and there will be many additional challenges to deal with. While religious and political issues will be the main themes one important and vital area must not be overlooked, that being the cultural heritage of Egypt, especially the unique, important and frequently neglected Coptic heritage.

In recent times we have seen the many conflicts in the Middle East, such as those in Libya, Afghanistan and Syria, and with them the increasing and serious damage to their many valuable archaeological and heritage sites. In addition, at the time of writing, important sites in Timbuktu are being damaged by religious extremists, only days after being declared World Heritage sites by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization).

It is unfortunate that currently only one major Coptic site in Egypt is on the UNESCO world heritage list, Abu Mena south of Alexandria, inscribed on the list in 2001. This is an extremely important site as it comprises many architectural elements and archaeology typical of the early Christian era. Remains demonstrate the construction of a Church, baptistery, basilicas, public buildings, streets and houses, workshops and monasteries. The original monastery was constructed in the 3rd century AD and commemorates the Alexandrian soldier Menas, an officer in Diocletian’s army. It was Menas who refused to kill any Christian, and even declared his Christianity publicly. There is a local legend that the remains of Menas were brought back from Phyrgia (in modern Turkey) by camel. When the camel refused to walk any further, the remains were buried at that spot. Thus the actual site of Abu Mena was eventually built over the remains of the martyr Menas, who died circa AD 296. Archaeology has revealed that the site expanded greatly in the 5th and 6th centuries, and by AD 600 the oasis had become a pilgrimage city.

There are many important and disappearing sites of the Early Coptic period in Egypt that should at least be considered as world heritage sites. These include Wadi el Natrun in the desert edges of the eastern Delta, the site of an important early Christian monastic tradition, with four functioning monasteries surviving today (and recently put forward to UNESCO for consideration) and Kellia, an important monastic site north east of wadi el-Natrun, which demonstrated the ‘bridge’ between the ascetic (lone) monks and the cenobitic (communal). Just as important is the vast Christian cemetery of el Bagawat near the Kharga oasis, with its painted private tomb-chapels, considered to be the oldest and largest Christian cemetery in the world. A few hour’s drive from Luxor it is now an increasingly busy tourist attraction and should certainly be considered for a place on the UNESCO list.

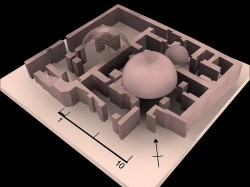

With these factors in mind, two years ago, with my colleague Peter Hossfeld from Zurich, I instigated the ‘Qubbat el-Hawa Project’ (figure 1). With the aid of 3D rendering software and by collating hundreds of high resolution photographs, the the project aims to deliver a complete rendering and virtual reconstruction of the Coptic Church at Qubbat el-Hawa, in the Elephantine area of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The aim of the project is to ‘freeze in time’ the typical structure of a Coptic site in order to protect and preserve this part of Egyptian heritage, including its unique and rapidly deteriorating wall paintings. In turn, the data provided would assist in future Coptic art and architecture restoration and conservation programmes, contributing to the ongoing protection of Coptic heritage.

The project initially started out as a conservation programme, but we rapidly realised that with new High Resolution photography, we were beginning to uncover not only hitherto unknown inscriptions but wall illustrations also. If the Qubbat el-Hawa site demonstrates what one can discover with a little time and the right equipment, what other ‘treasures’ may be found to uncover throughout the full extent of the unique Coptic heritage.

Qubbat el-Hawa Historical Background

The name Qubbat el-Hawa, in Arabic often referred to as ‘Dome of the wind’, originates from the domed mausoleum (‘qubbat’) of Sheikh Ali Abu ‘l-Hawa, which is located above the site on top of a sand hill.

The best known Coptic site in the area is the monastery of Saint Simon some distance out into the desert beyond Aswan. Few visitors to the well known Pharaonic tombs of Qubbat el_Hawa are aware of a second set of monastic remains, including a Coptic church, which occupy the same area as the rock-cut tombs.

The site of the Coptic Church is situated on the slope of the hill of Qubbat al-Hawā, to the west of Aswan, which is honeycombed with ancient rock-cut tombs of local high officials of the 6th Dynasty and later. These tombs are arranged on four levels, The Coptic Church remains, dating to the 8th – 10th Century AD and surrounded by earlier hermitage remains, is located on the uppermost level, in front of the Pharaonic tomb Khunes (QH 34h) and formerly part of the monastic settlement. The material remains of much of this site are currently only partly documented. The most notable Coptic features are the remains of the church in front of the tomb of Khunes, with the remains of a mud-brick residential building above.

In 1998, the then Supreme Council of Antiquities excavated the site and exposed many of the Coptic wall paintings and inscriptions unprotected to the ravages of the desert climate. Unfortunately, the uncovered wall illustrations and the Arabic and Coptic texts were not systematically recorded or photographed, and no excavation reports are as yet available. There is now considerable erosion on the site and therefore urgent documentation and restoration work is required in order to save these important remains.

Figure 4. Recent cornerstone illustration discovery of a figure in Monastic garments (Howard Middleton-Jones 2010)

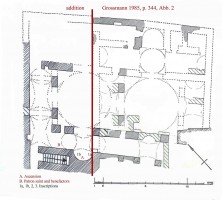

In January 2010, the Supreme Council of Antiquities resumed the excavation of the Church and uncovered part of the original floor, including the footings of the west and north walls. Updated plans of the church and the site have been constructed by Renate Dekker of Leiden (2008) demonstrating that the building was reached by means of the ancient staircase in front of the Sixth Dynasty tomb of Khunes and currently used by the visitors to access the site (figure 2).

Until recently, only the tombs of Khunes (QH 34h, figure 3) and Khui (QH 34e) were explicitly mentioned as having been part of the monastic complex, while various systems of basins and new floors and ‘numerous dividing walls’ were observed ‘in the adjacent tombs. The excavations by the University of Jaén in Spain (2008 to the present) have also yielded Christian iconographical and textual material from the tombs QH 33, 34c, 34f, 104, 105 and 110.

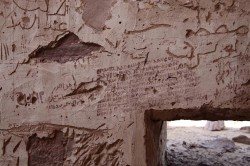

As part of the on-going Qubbat el-Hawa Virtual Project, in 2009 and 2010 (Note 1) a high-resolution photographic survey was conducted by Peter Hossfeld in 2009 and the author in 2010 resulting in the discovery of hitherto unknown Coptic texts and illustrations. These latest important discoveries, which require further investigation and analysis, will contribute greatly to a new history of the Coptic Church (figure 4).

The Wall Paintings

There are a number of important wall illustrations present on the site, especially on the Western Apse and Northern wall. However, these are rapidly eroding and require immediate restoration. Some examples are given below.

On the Western apse there are scenes divided into upper and lower zones. In the upper zone painted on white plaster, is a depiction of a mandorla (Vesica Piscis; an ancient symbol of two circles overlapping to form an almond shape) with a bust of Christ

Only his chin, beard and part of his yellow nimbus are visible. He holds a book in his left hand, while raising the other hand in blessing.

The mandorla is carried by six angels who appear to be in flight.

The lower zone is set within a red frame depicting the Holy Virgin flanked by twelve Apostles.

The wall paintings to the North of the apse on the West wall depict six men. Four of the figures (on the left side) are dressed in monastic garments, while a fifth figure wears a white garment with an omophorion-like collar (a wide cloth band draped around the shoulder, corresponding to the Western pallium) distinguishing him as a priest.The sixth figure appears to be a Saint, who is clothed in a white tunic holding a book in one hand and being represented as taller than the other five figures. This figure probably represents the Patron Saint of the Church. Generally saints may be recognised in art from their garb and objects they hold but in this case identification remains elusive although we might speculate that the book, were it a gospel (which is likely in the 8th – 10th centuries), would indicate a sainted bishop.

Texts and Inscriptions

Figure 7. Overview of the lower Coptic Church remains from above the Apse (Howard Middleton-Jones 2010)

The majority of the later Coptic and Arabic inscriptions appear to date from the Coptic year 841 (AD 1125) however, earlier inscriptions are in evidence and more research is required to undertake a fuller record. However, it appears that in 1125 Bishop Severus (presumably Bishop of Aswan) consecrated this ‘new Church’ and the baptismal font, while dedicating it to the Patriarch Severus of Antioch.

Unfortunately much of the earlier inscriptions are over written with considerable later Arabic graffiti.

Comparing the available photographs taken in 2003, 2005, 2008, 2009 and 2010 rapid deterioration of the wall paintings and inscriptions is evident. It is crucial therefore for steps to be instigated to develop a conservation programme for this unique site. Regrettably, the likelihood of such a programme seems far from the realms of possibilities, especially with the complex current situation in Egypt.

With this in mind, it is imperative that the work of the on-going Qubbat el-Hawa VR (Virtual Reconstruction) project be promoted and concluded post haste. As with all digital records, formulation of the plan for the long term curation and preservation of the archive is equally vital.

By implementing such technologies at ancient sites such as Qubbat al-Hawa, we may promote an understanding of past cultures and display such unique features and sites within the growing area of cultural heritage. This in turn will hopefully encourage prospective archaeologists, Egyptologists, Coptologists and related heritage workers, to promote and demonstrate an awareness of the important areas of conservation of our cultural heritage.

Call to Action

It is vitally important that the Coptic heritage in Egypt should be taken seriously and with some urgency, with a plan of campaign put in place to preserve these vitally important sites and monuments. Many of the Coptic sites in Egypt more than qualify under the regulatory operational guidelines and certainly pass the criteria for submitting a site for assessment, as demonstrated in the UNESCO Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (WHC. 11/01November 2011). I hope that with the new government in place in Egypt and with the newly re-constructed Department of Antiquities, we may see a step in the right direction towards a major development in protecting these vulnerable sites.

Note 1

Qubbat el-Hawa Project – the Virtual 3D Reconstruction of a Coptic Church Elephantine Aswan: Howard Middleton-Jones (UK), Peter Hossfeld (Switzerland) and Reneta Dekker (Holland)

http://ambilac-uk.tripod.com/qubbatalhawaproject/

Image Credits

All photographs are copyright as per image captions.

Bibliography

Dekker. R (2008) ‘New’ Discoveries at Dayr al Qubbat al-Hawa, Aswan. Architecture, Wall Paintings and Dates. EAC 5 pp 19-36

Gabra. G (2002) ‘Coptic Monasteries: Egypt’s Monastic Art and Architecture. The American University in Cairo Press. Cairo

Grossman, P (1991) ‘Dayr Qubbat al-Hawa Architecture’ CE 3 pp 851-852

Middleton-Jones 2010 The Coptic Monasteries Multi-Media Database Project in ‘Christianity and Monasticism in Upper Egypt Volume 2 – Nag Hammadi-Esna’ Eds Gabra G and Takla H.N. The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

Middleton-Jones (2012 forthcoming) The Dayr Qubbat al-Hawa Project in ‘Christianity and Monasticism in Upper Egypt Volume 3 – Aswan’ Eds Gabra G and Takla H.N. The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo

Biography

Howard Middleton-Jones is the tutor for the Archaeology and Coptic Studies programme in the Adult Continuing Education, Humanities College, Swansea University. Howard gained his degree in Ancient History and Classics at Swansea University and attended Oxford University where he undertook the Post Graduate Field Archaeology programme. He has been a corporate member (PIFA) of the Institute of Archaeology for over 15 years, a member of the International Association of Coptic Studies (IACS) and is a regular traveller to Egypt presenting papers at the Coptic symposiums.

By

By